Martin Luther King Jr. Federal Holiday

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated by a white racist in Memphis, TN. Just hours before, King had given a speech to city sanitation workers who were on strike. King was a charismatic, eloquent, and highly visible leader of the non-violent civil rights movement in America. He had won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Almost immediately, there were calls for ways to memorialize King and preserve his legacy.

On April 8, 1968 John Conyers (D MI-1) introduced HR 16510, to make King’s birthday a “legal public holiday.” The bill was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary. [See Congressional Record-House 4/8/1968, p. 9187.] The Committee took no action on the legislation.

Consistently thereafter, bills to create a MLK holiday were introduced in the House, sponsored by Conyers and others.

Carter’s Support

Not until 1979, in the Administration of Jimmy Carter, did any of these bills even get out of committee, much less reach the House floor for a vote.

In January 1979, Carter announced his support for the MLK holiday in his State of the Union Message. There was, apparently, considerable public support for the holiday. On December 5, 1979, the House passed a resolution providing for the consideration of legislation (HR 5461) to establish a MLK holiday on the third Monday in January. But the legislation did not pass the House.

Carter’s highly visible support was not sufficient.

Nonetheless, public support for the bill continued to grow, encouraged in part by musician Stevie Wonder. Wonder’s 1980 album Hotter Than July featured the song “Happy Birthday,” a kind of ode to King's vision. The Smithsonian has called it “a rallying cry for recognition of his achievements with a national holiday.”

Reagan’s Ambivalence

President Reagan’s ambition to reach out to Black voters, and his personal commitment to non-discrimination shaped the next rounds of consideration of the holiday. [See the discussion of the period in Cannon, President Reagan in chapter 17.]

In a Q&A session with high school students at the White House on January 21, 1983, Reagan expressed his support for “a day to remember” MLK, but he explicitly did not support a paid national holiday.

On August 2, 1983, the MLK Holiday bill was discharged from House Committee on Post office and Civil Service by Suspension of the rules. A “discharge” is a rarely-used a means of bringing a bill out of committee without a report from the committee—i.e., removing the Committee’s agenda-setting power over legislation. To do this requires the signatures of a majority of the members of the House. After discharge, the bill passed the House 338-90. [See a Congressional Research Service report on these petitions, available as a pdf.]

The MLK holiday legislation was immediately introduced in Senate. Senators Theodore Kennedy (MA) and Charles Mathias (MD) managed the legislation in the Senate.

Days later, on August 6 1983, the White House announced the President was “leaning toward endorsing” the holiday legislation [New York Times August 7, 1981, p 1].

Nonetheless, on October 3, North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms started a filibuster against the MLK holiday legislation [New York Times October 4, 1983, p.17]. But on the same day, the Times reported that President Reagan had revealed his decision to sign the bill under consideration if it passed the Senate. The next day, Helms stopped his filibuster and agreed to a Senate vote later in the month. [New York Times October 5, 1983, p. 16].

In mid-October, Senate considered and rejected many amendments to the MLK Holiday legislation all of them to dilute its visibility and status. On October 18 amendments considered include:

- · to create a holiday to be known as “National Equality Day” (rejected 22-68; Sen. Rudman, NH, sponsor)

- · to create a national commemorative day, not a holiday, to be known as “National Civil Rights Day” (rejected 18-76, Sen. East, NC, sponsor),

- · to make MLK’s actual birthday (1/15) a “day of commemoration”—not a paid Federal holiday--(rejected 24-69, Senator Exon, NB, sponsor),

- · to provide a full Federal holiday on MLK’s actual birthday (rejected 23-69 Sen. Randolph, WV sponsor),

- · and from Senator Jesse Helms, to obtain Senate access to Federal Records on MLK (rejected 3-90). Helms was seeking access to records of FBI wiretaps of King and possible reports of MLK’s communist associations.

In debate on these amendments, critics pointed out (as had been done many times prior) that except for George Washington, no individuals have been honored by the creation of US holidays. They suggested that many others might be equally deserving of such recognition as might some cause that could be linked to a president, such as physical disability (e.g., Franklin D. Roosevelt).

On the October 19, the Senate considered an amendment by Senator Humphrey (MN) to change the day of the MLK holiday from Monday to Sunday. This was defeated 16-74.

Humphrey then offered another amendment to create a Lincoln Birthday holiday on the second Sunday in February. With little discussion, this amendment was also defeated 11-83.

Senator Helms then offered yet another amendment specifying that the MLK holiday would take effect only if a new holiday were created to honor Thomas Jefferson, and providing that the total number of Federal holidays could not exceed nine. This amendment was defeated 10-82.

On October 19, the MLK holiday proposal passed the Senate 78-22. (Congressional Record—Senate, p. 28380)

In a prime-time news conference on October 19, 1983, after the Senate action, ABC News reporter Sam Donaldson asked President Reagan: “Mr. President, Senator Helms has been saying on the Senate floor that Martin Luther King, Jr., had Communist associations, was a Communist sympathizer. Do you agree?”

Reagan responded that he did not doubt Senator Helms’s sincerity, and that “we’ll know in about 35 years,” when the papers are opened, about King’s communist associations. Reagan went on to say that he would have preferred a day of recognition, not a national holiday.

On November 2, 1983, Ronald Reagan signed the bill making Martin Luther King Jr’s birthday a federal holiday.

Presidential Mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr.

We have noted that MLK holiday legislation did not pass curing Jimmy Carter’s Administration despite Carter’s explicit support. It did pass under Ronald Reagan despite Reagan’s explicit preference for something different--weaker.

One of the truisms of American politics emerging with Franklin D. Roosevelt, has been that Black Americans have tended to vote for Democrats in national elections. So what would we expect about Presidential behavior—specifically acknowledgement and appreciation of Black political luminaries like Martin Luther King, Jr.?

On the one hand, we expect to see Democrats systematically underscoring their connections to a key group in their coalition.

On the other hand, we might expect Republicans to be ready to reach out when they see an opportunity to draw support from a key Democratic group.

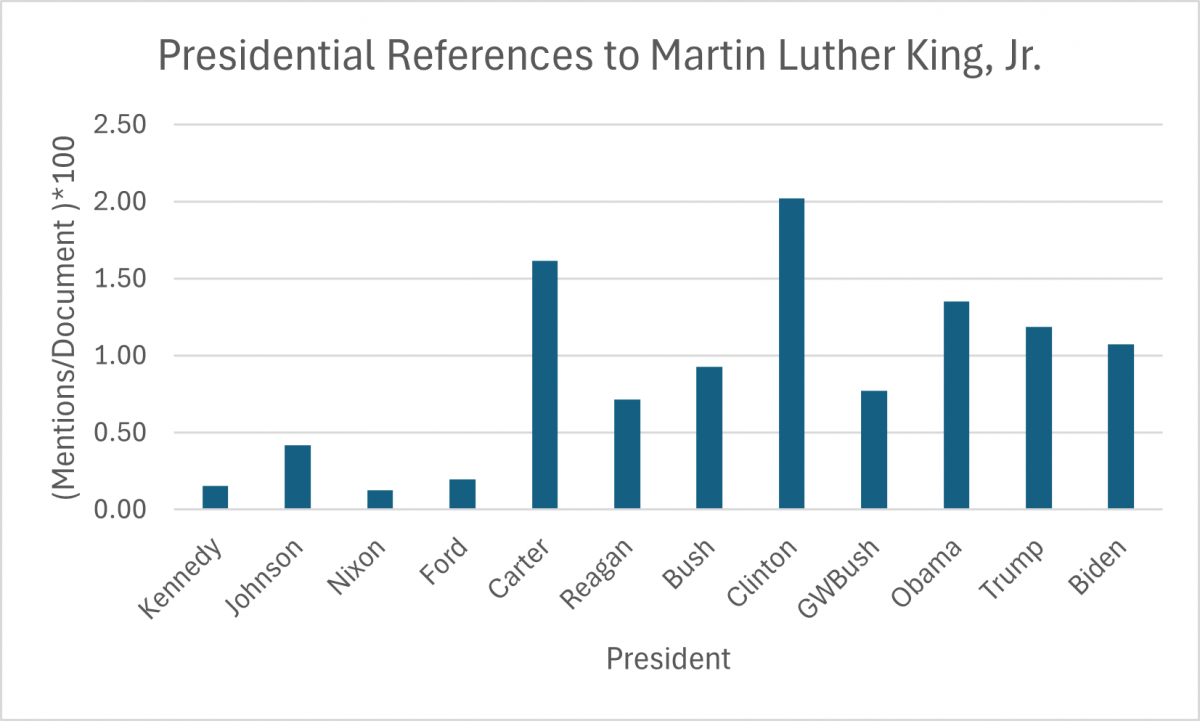

One possible indicator of this is simply the relative frequency of mentioning of Martin Luther King Jr. by presidents. This is shown in the graph below, which displays the rate of mention of Martin Luther King per presidential document (i.e., excluding documents from the Press Office or other White House Units).

It is not surprising that Nixon and Ford mentioned MLK far less frequently than did Carter. It is interesting that Reagan, while dropping off a lot from Carter, still exceeded Nixon and Ford rates by a large margin. A surprise here is the result for Trump (1st term), whose rate of MLK mentions slightly exceeded Biden’s.

This finding is consistent with the notion that Trump has seen, and pursued, an opportunity to build support among Black Americans.