Martin Luther King Jr., the Atlanta native who became one of the most important figures in the civil rights movement, was born on January 15, 1929. While it would be impossible to encompass everything King accomplished in a mere list, we’ve compiled a few intriguing facts that might pique your interest in finding out more about the man who helped unite a divided nation.

- Martin Luther King was not his given name.

- King was a doctor of theology.

- He made 30 trips to jail.

- The FBI tried to coerce King into suicide.

- Civil rights history could have been altered by a single sneeze.

- King got a C in public speaking.

- He won a Grammy.

- He loved Star Trek.

- King spent his wedding night in a funeral parlor.

- Ronald Reagan was opposed to a Martin Luther King holiday.

- We could see King on the $5 bill—at some point.

- One of King’s volunteers walked away with a piece of history.

Martin Luther King was not his given name.

One of the most recognizable proper names of the 20th century wasn’t actually what was on the birth certificate. The future civil rights leader was born Michael King Jr. on January 15, 1929, named after his father Michael King. When the younger King was 5 years old, his father decided to change both their names after learning more about 16th-century theologian Martin Luther, who was one of the key figures of the Protestant Reformation. Inspired by that battle, Michael King soon began referring to himself and his son as Martin Luther King.

King was a doctor of theology.

Using the prefix doctor to refer to King has become a reflex, but not everyone is aware of the origin of King’s Ph.D. He attended Boston University and graduated in 1955 with a doctorate in systematic theology. King also had a Bachelor of Arts in sociology from Morehouse College and a Bachelor of Divinity from Crozer Theological Seminary.

He made 30 trips to jail.

Opponents tried to silence King—a powerful voice for an ignored and suppressed minority—the old-fashioned way: incarceration. In the 12 years he spent as the recognized leader of the civil rights movement, King was arrested and jailed 30 times. Rather than brood, King used the unsolicited downtime to further his cause. Jailed in Birmingham for eight days in 1963, he penned “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” a long treatise responding to the oppression supported by white religious leaders in the South.

“I’m afraid that it is much too long to take your precious time,” he wrote. “I can assure you that it would have been much shorter if I had been writing from a comfortable desk, but what else is there to do when you are alone for days in the dull monotony of a narrow jail cell other than write long letters, think strange thoughts, and pray long prayers?”

The FBI tried to coerce King into suicide.

King’s increasing prominence and influence agitated many of his enemies, but few were more powerful than FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. For years, Hoover kept King under surveillance, worried that he could sway public opinion against the bureau and fretting that King might have communist ties. An anonymous letter—likely written by Hoover’s deputy William Sullivan, who may or may not have been acting on Hoover’s orders—was sent to King in 1964 accusing him of extramarital affairs and threatening to disclose his indiscretions. The only solution, the letter suggested, would be for King to exit the civil rights movement, either willingly or by dying by suicide. King ignored the threat and continued his work.

Civil rights history could have been altered by a single sneeze.

Our collective memory of King always has an unfortunate addendum: his 1968 assassination that brought an end to his personal crusade against social injustice. But if Izola Ware Curry had had her way, King’s mission would have ended 10 years earlier. At a Harlem book signing in 1958, Curry approached King and plunged a 7-inch letter opener into his chest, nearly puncturing his aorta. Surgery was needed to remove it. Had King so much as sneezed, doctors said, the wound was so close to his heart that it would have been fatal. Curry, a 42-year-old Black woman, was having paranoid delusions about the NAACP that soon crystallized around King. She was committed to an institution and died in 2015.

King got a C in public speaking.

King’s promise as one of the greatest orators of all time was late to emerge. While attending Crozer Theological Seminary from 1948 to 1951, King’s marks were diluted by C and C+ grades in two terms of public speaking.

He won a Grammy.

At the 13th annual Grammy Awards in 1971, a recording of King’s 1967 address, “Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam,” took home a posthumous award for Best Spoken Word recording. In 2012, his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame (it was included decades later because its 1969 nomination was beaten for the Spoken Word prize by Rod McKuen’s “Lonesome Cities”).

He loved Star Trek.

It’s not easy to imagine King having the time or inclination to sit down and watch primetime sci-fi on television, but according to actress Nichelle Nichols, King and his family made an exception for Star Trek. In 1967, the actress met King, who told her he was a big fan and urged her to reconsider her decision to leave the show to perform on Broadway.

“My family are your greatest fans,” Nichols recalled King telling her, and said he continued with, “As a matter of fact, this is the only show on television that my wife Coretta and I will allow our little children to watch, to stay up and watch because it’s on past their bedtime.” Nichols’s character of Lt. Uhura, he said, was important because she was a strong, professional Black woman. If Nichols left, King noted, the character could be replaced by anyone, since “[Uhura] is not a Black role. And it’s not a female role.” Based on their talk, Nichols decided to remain on the show for the duration of its three-season original run.

King spent his wedding night in a funeral parlor.

When King married his wife, Coretta Scott, in her father’s backyard in 1953, there was virtually no hotel in Marion, Alabama, that would welcome a newlywed Black couple. A friend of Coretta’s happened to be an undertaker, and invited the Kings to stay at one of the guest rooms at his funeral parlor.

Ronald Reagan was opposed to a Martin Luther King holiday.

Despite King’s worthiness, MLK Day was not a foregone conclusion. In the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan largely ignored pleas to pass legislation making the holiday official out of the concern it would open the door for other underrepresented groups to demand their own holidays; Senator Jesse Helms, Republican of North Carolina, complained that the missed workday could cost the country $12 billion in lost productivity, and both were worried about King’s possible communist sympathies. Common sense prevailed, and the bill was signed into law on November 2, 1983. The holiday officially began being recognized in January 1986.

We could see King on the $5 bill—at some point.

In 2016, the U.S. Treasury announced plans to overhaul major denominations of currency beginning in 2020. Along with Harriet Tubman adorning the $20 bill, the plan called for the reverse side of the $5 Lincoln-stamped bill to commemorate “historic events that occurred at the Lincoln Memorial” including King’s famous 1963 speech. In April 2018, though, the Trump administration announced that those plans were on hold and the bills would be delayed by at least six years.

One of King’s volunteers walked away with a piece of history.

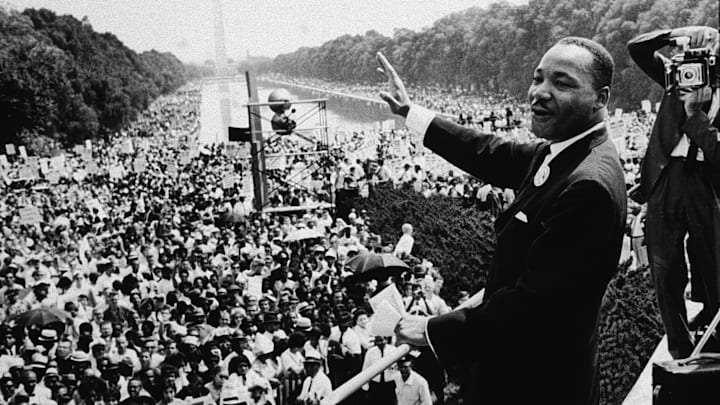

King’s 1963 oration from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, known as the “I Have a Dream” speech, will always be remembered as one of the most provocative public addresses ever given. George Raveling, who was 26 at the time, had volunteered to help King and his team during the event. When it was over, Raveling sheepishly asked King for the copy of the three-page speech. King handed it over without hesitation; Raveling kept it for the next 20 years before he fully understood its historical significance and removed it from the book he had been storing it in.

He’s turned down offers of up to $3.5 million, insisting that the document will remain in his family—always noting that the most famous passage, where King details his dream of a united nation, isn’t on the sheets. It was improvised.

Read More About History:

A version of this story ran in 2019; it has been updated for 2025.