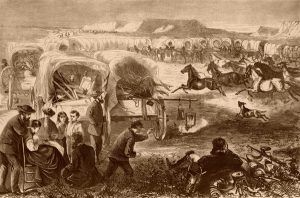

On the road from the fort… I saw a wagon — tolerable good but heavy — bacon, beans, stoves, chairs, iron wedges, crowbar, soap, lead, ovens, and many other articles all laying about in the prairie. They could not use them, and they could not carry them, and the only alternative was to leave them.

— Israel F. Hale, 1849

Blazing the Trail

The first emigrant wagon train bound for California, known as the Bidwell-Bartleson Party, struck out from Independence, Missouri, in the spring of 1841. “Our ignorance of the route was complete,” admitted John Bidwell, a 21-year-old Pennsylvania schoolteacher who lent his name and leadership to the wagon company. “We knew that California lay west, and that was the extent of our knowledge.”

That was the extent of almost everyone’s knowledge. The trail in 1841 was barely a track worn along the Platte River by the pack-mule and cart caravans of the Rocky Mountain fur trade. Hopeful greenhorns would have no beaten wagon road to follow over plain and mountain to California or Oregon.

No helpful map of the route existed. Emigrants would find no road signs, bridges, or ferries at river crossings and no place to replace exhausted oxen and food supplies. The 68 souls who first set out with John Bidwell into that arid unknown have been praised as bold visionaries and spurned as risk-taking fools.

Whatever they were, they were lucky. A few days out of Independence, Missouri, they joined up with Thomas “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick, who was already guiding a company of missionaries to the Pacific Northwest. The famous mountain man agreed to take the emigrants along the Platte River and through the Rocky Mountains as far as the Fort Hall area in present-day Idaho. From there, they would have to find their way. Amazingly, they did.

The way Fitzpatrick took his pilgrims — on the old trappers’ route up the North Platte River into central Wyoming, up the Sweetwater River, and over South Pass — became the corridor of the combined Oregon, California, Mormon, and Pony Express Trails. Government maps of the route published in 1843 and 1845 gave others the confidence to set out for the West. A rising stream of emigrant wagons had beat the old “fur trace” into a road that the greenest tenderfoot could follow within a few years.

Approaching the Rocky Mountains

Most emigrants agreed that the easiest part of the overland trail was the 500-mile stretch that followed the Platte River across Nebraska’s prairie. The country grew rougher, and the scenery more incredible as the wagons rumbled up either side of the Platte River’s north fork, past Chimney Rock and Scotts Bluff, and into Wyoming, in the vicinity of present-day Lingle. The trail crossed an undistinguished grassy flat where an 1854 shootout between Sioux and soldiers, known as the Grattan Fight, would unleash the bloody Plains Wars. A shallow mass grave and grisly artifacts marked the battle site for the continuing emigration.

By the time travelers reached that sober milestone, they had been six to eight weeks on the trail. The weary rhythm of the road demeaned their enthusiasm for wayside points of interest: rise before dawn, cook, clean up, repack, gather and yoke the oxen… and then plod through the dust all day to set up another camp about 12-15 miles up the road. Fort Laramie, 50 miles west of Scotts Bluff, Nebraska, provided a welcome break from the monotony.

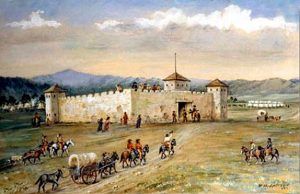

In 1841, when the Bidwell-Bartleson Party stopped in for a two-day layover, the fort (then called Fort John) was a simple adobe trading post bustling with fur traders, trappers, Plains Indians, and adventurers. Eight years later, the U.S. Army purchased the establishment of a military post to protect and help re-supply the ever-increasing overland traffic. Fort Laramie soon grew into an active community of soldiers, army wives, laundresses, children, servants, and quartermaster employees. Teepee encampments settled in and around the fort, becoming a multi-ethnic “travel plaza” on the overland highway. There, emigrants could post their mail, repair wagons, shoe livestock, and shop for necessities (and liquor) at the post-sutler’s store. They also could visit and trade with the fort’s Indian residents — a thrill that many emigrants recorded in their trail journals.

Most travelers approached Fort Laramie from the main Oregon and California roads along the south bank of the North Platte River. This required fording a tributary, the Laramie River, just east of the fort. Today, dams have tamed the Laramie River, but in the mid-1800s, the river’s spring current sometimes toppled wagons and drowned emigrants and livestock. Looking for the safest places to ford, travelers used at least nine different crossings of the Laramie River, and bridges and ferries eventually served some locations.

In the early years of emigration, the terrain on the river’s north side was considered impassable west of Fort Laramie. Mormon emigrants and others entering Wyoming on the north-bank road were forced to ford the deep, swift North Platte River near the fort. Starting in 1850, north-side emigrants had the option of loading their wagons into a ramshackle flatboat and pulling the contraption along a rope stretched across the river — unassisted and at the outrageous fare of $1 per wagon. The price of passage drove some offended emigrants to blaze a new trail, Child’s Cutoff (also called Chiles’s Route), which continued west on the north side of the river. Travelers on the north bank via Child’s Cutoff could avoid crossing the North Platte River altogether. At the same time, those following the original south-bank road had to cross upstream, near present-day Casper. By 1852, most wagons arriving on the north side continued up Child’s Cutoff, though many travelers still crossed the river to visit Fort Laramie. A graceful iron military bridge, built in 1875, still spans one of four emigrant crossings of the North Platte River near the fort. Sparkling placidly beneath the bridge, the river strikes today’s summertime visitor as a pleasant wade, unlike the fearsome mountain torrent of 150 years ago.

Whether the pioneers traveled north or south of the river, Fort Laramie was a significant milestone, sitting at the edge of the western plains where the land begins to lift toward the slopes of the Rocky Mountains. The blue-gray beacon of Laramie Peak rose west of the fort, looking “like a dark cloud on the western horizon,” according to John Bidwell. The road’s steepest, roughest, driest, and most dangerous stretches lay ahead. Travelers paused to lighten their wagons by selling unnecessary items — tools, books, clothing, furnishings, even wagons, and food — at Fort Laramie, but buyers were scarce. Most disappointed sellers destroyed or dumped their possessions along the trail and moved on. Forty-niner J. Goldsborough Bruff saw “bacon in great piles, many cords of it” and a “diving bell and all the apparatus” among the items abandoned in the Wyoming dust.

Ten miles northwest of the army post, travelers on the south side of the river reached their next campsite, called Sand Point, near today’s Guernsey, Wyoming. (In 1860-61, the Centre Star Pony Express station was also located here.) Some paused between endless camp chores to carve their names into the soft stone face of Register Cliff.

A few miles beyond, the wagons fell into a single file for a hard pull up a rock ridge, avoiding boggy ground nearer the river. Thousands of iron-shod hooves and wagon wheels gradually cut a vertical-walled channel deep into the stone at a site now known as the Guernsey Ruts or Deep Hill Ruts.

The trails followed the arc of the North Platte River deep into central Wyoming. Once wagons started taking Child’s Cutoff, profit-minded men established toll bridges and ferries at several locations between Fort Laramie and present-day Casper. These allowed wagons to zigzag back and forth across the river to avoid sandhills and other tricky spots. At Casper, the river curved southwest across the emigrant route, forcing those on the south side to make a final crossing there or a few miles further west near Red Buttes (now called Bessemer Bend.) And that was the end of the Platte River lifeline that had conducted the emigration across hundreds of miles of prairie and plain. Now, the need for water and grass would become a nagging worry.

A short distance beyond the last crossing of the North Platte River at Red Buttes, all the trails came together for the hot, hard haul over Devil’s Backbone (also known as Avenue of Rocks) to the next good water at Willow Spring. Along this stretch, travelers on all the trail variants and cutoffs of the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails merged for the first time into the same road. Now their teams faced a long pull-up Prospect Hill, where wagon wheels wore multiple ruts and swales still visible today.

The next watering hole for the thirsty oxen was two miles farther: an odorous alkali marsh called Clayton’s Slough, jokingly named after an 1847 Mormon pioneer who had nothing good to say about the place. Hardworking oxen (and people) that drank too deeply of the alkaline water often died of digestive upsets and dehydration. Good water was available about four miles west at Horse Creek, where a Pony Express station stood in the 1860s. The road stretched another ten dry miles to the Sweetwater River. The grass was scarce all along the route.

This leg of the trip, Emigrant Gap (today sometimes called the Poison Spider Route), was a bitter introduction to what lay ahead: long stretches of hot, hilly trail with little feed for the animals, punctuated with stinking, toxic alkali waterholes. That poisonous 30-mile stretch between the North Platte River and the lovely Sweetwater Valley would kill many an ox and emigrant through the overland trail years.

Sweetwater to South Pass

The vast granite loaf of Independence Rock signaled temporary relief from the thirsty barrens, for it stands where the emigrant trail meets the Sweetwater River. Trail tradition held that reaching this milestone by July 4 meant the emigrants would arrive safely in Oregon or California before early blizzards blew. People often paused here to rest their livestock and explore the formation, probably the most famous landmark on the combined Oregon, California, Mormon, and Pony Express routes. Many travelers chiseled or painted their names on the outcrop, turning Independence Rock into a permanent memorial to the passing emigration.

Independence Rock also marked the beginning of South Pass, for the pass was not just the single point where the trail crested the Continental Divide. In the minds of emigrants, it was the entire 100-mile climb up the Sweetwater River to the divide. Emigrants and oxen on this uphill stretch would have good water — and lots of it, as they would cross the cold, meandering Sweetwater nine times. Even here, though, in peak emigration years, the grass was scarce, and livestock went hungry.

People, as well, suffered along this stretch of trail. In the Sweetwater Valley, many travelers began taking sick with a mysterious, aching ailment they called “mountain fever.” They blamed their illness on mosquitoes, altitude, and the alkali dust, but doctors today think it was a tick-borne disease such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

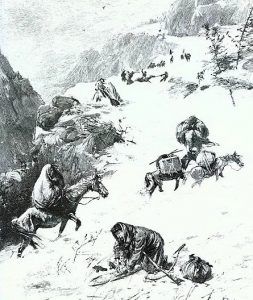

And, as they climbed toward the mountain pass, emigrants regretted having abandoned warm bedding and clothing along the trail. High elevations can bring chilly summertime winds, freezing nighttime temperatures, and the threat of a snowstorm in July. The weather in this mountain country has been known to deliver disaster to the unprepared. In 1856, an October blizzard trapped four late-departing Mormon handcart and wagon companies, with nearly 1,400 men, women, and children among them, in the Sweetwater Valley. Despite the heroic efforts of rescuers from Salt Lake City, many of the emigrants — historians count range from about 170 to over 300 — did not survive the ordeal.

Mountain-rimmed Sweetwater Valley can be cold and ruthless but is also a place of sublime natural beauty. Despite the hazards they faced there, some awestruck 19th-century emigrants paused to write poetically about this trail segment.

As they trekked up the Sweetwater Valley, travelers passed several notable trail milestones. First was Devil’s Gate, a natural curiosity that puzzled many an emigrant: what caused the Sweetwater River to chew and channel through the ridge instead of flowing around it? Then came Split Rock, a “gun-sight” notch in the Rattlesnake Range that aimed travelers directly toward South Pass, some 75 miles distant. At Ice Slough, astonished emigrants dug clear, sweet ice — a treat! — from beneath the turf in mid-summer. Barren, wind-slapped Rocky Ridge, a 700-foot climb through broken rock, was always an ordeal for wagons and teams, particularly for Mormon emigrants pulling loaded handcarts. Finally, the trail threaded between Twin Mounds, two low hills that marked the final approach to the Continental Divide. Through the years of emigration, this Sweetwater-to-South Pass stretch also became dotted with trading posts, Indian and army encampments, and Pony Express, stage, and telegraph stations.

To the northwest bared the ferocious, snow-covered sawteeth of the Wind River Range, which fretted many an emigrant. It was a needless worry as the trail passed south of the Wind Rivers, not through them. The grade up and over South Pass, about 7,550 feet in elevation, is so gradual and mild that most travelers never knew exactly when they crossed the Continental Divide. In his journal entry of July 18, 1841, John Bidwell noted casually, “Crossed the divide which separates the water of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.”

The long-anticipated crossing of the Great Divide was a letdown. But, travelers to Oregon and California were still less than halfway through their journey. More serious challenges lay ahead.

After sharing a broad common corridor through Nebraska and Wyoming, overland traffic burst up and over the Continental Divide like spray from a hose. Three main trunk routes, linked by a snarl of alternative cutoffs, fanned out across western Wyoming: the Lander Road, the Sublette Cutoff, and the Fort Bridger route.

The Lander Road, the only wagon road in the overland trail system built with federal funds, was the last of the three routes to be opened. Frederick W. Lander, a government engineer with the Department of the Interior, surveyed and built the road in 1857-59 to improve transportation to the western states. Lander saw that many travel problems, including the suffering of the oxen, arose from “the extreme dryness and heat of the sagebrush deserts,” so he routed his cutoff on the northern side of South Pass through the cooler, higher areas with more grass and water.

The Lander Road forked off the main trail at the ninth crossing of the Sweetwater River, just east of the Continental Divide, and angled northwest. It crested the divide north of today’s Highway 28, entered Idaho west of present-day Auburn, Wyoming, and rejoined the main Oregon and California road near Fort Hall, Idaho. This northern route stayed well clear of Utah, where troubles were brewing between the federal government and the Mormon followers of Brigham Young. For a while, though, the Lander Road was a preferred stalking ground of “white Indians” — white men disguised as Indians — who lured emigrant families away from the main road and cruelly murdered them for their belongings. White criminals were responsible for several ruthless incidents on Lander Road in 1859.

The main trail on the southern side of South Pass headed toward the bright green marsh of Pacific Springs, just west of the Continental Divide. Cattle would mire themselves at this swampy campsite if their owners did not take care, but Pacific Springs provided the last good water and abundant feed they would find for a couple of days. From here, travelers entered a grassless, gray-green ocean of sagebrush, starvation country for the weary oxen. The next water was about ten miles ahead at Dry Sandy Crossing, a miserable spot where alkali pools fatally poisoned several oxen belonging to the Donner-Reed Party in 1846. The loss of those animals contributed to their problems farther down the trail.

Fort Bridger, Wyoming

About 20 miles west of the Continental Divide, the main road forked at a spot called Parting of the ways — a point of decision. From there, travelers could either follow Lander Road or the Sublette Cutoff heading due west toward the trading post at Fort Hall or take the original, better-watered route southwest toward Fort Bridger and Utah.

The Sublette Cutoff was blazed in 1844. Until the Lander Road opened 15 years later, most emigrants to California and Oregon chose the Sublette Cutoff because it was about two days faster than the Fort Bridger route. But, the Sublette Cutoff crossed 45 miles of pitiless desert between the Big Sandy and Green Rivers. Emigrants filled up every container at the Big Sandy River and started toward the Little Colorado Desert in the cool of the evening. Dawn would catch them with many burning miles yet to go. Once over the desert, travelers still had to cross the dangerous Green River, said to claim a life a day, and climb several ridges. Some of the ridges are over 8,000 feet higher than South Pass. The Sublette Cutoff was the shorter way, but it was an ox-killer.

The Fort Bridger road was dry and torturous, too, but at least the cattle could water at the Big Sandy at the end of each day. The original Oregon-California route continued southwest from Parting of the Ways, paralleled the Big Sandy River to the Green River crossings, and went to the Blacks Fork and Fort Bridger.

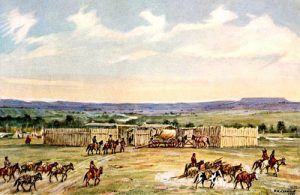

Fort Bridger, built by mountain men Jim Bridger and Louis Vasquez as a trading post in 1843, was another place of decision for emigrants. They could pause at the fort to rest, re-supply, turn northwest, and rejoin the Sublette and Lander Road traffic east of Fort Hall. Or, after 1846, those bound for Utah and California could continue southwest from Fort Bridger on the Hastings Cutoff, named for California promoter Lansford W. Hastings. This was the infamous “shortcut” that the Donner-Reed Party painfully punched through the Wasatch Range, into the Salt Lake Valley, and across the Great Salt Desert. For them, the Hastings Cutoff was a shortcut to disaster.

For others, it was a blessing. The following summer, Brigham Young and his followers took that same hard-won track out of Fort Bridger toward the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.

Source: National Park Service. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2023.

Also See:

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

California Trail – Rush to Gold

Fort Bridger State Historic Site