By Henry Inman and William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, 1898.

As early as the first decade of the present century, the great fur companies sent out expeditions up the valley of the Platte in the charge of their agents to trap the beaver and other animals valuable for their beautiful skins. The hardships of these pioneers at the beginning of a trade that, in a short time, assumed gigantic proportions are a story of suffering and privation that has few parallels in the history of the development of our mid-continent region. Until the establishment of the several trading posts, the lives of these men were continuous struggles for existence, as no company could transport provisions sufficient to last beyond the most remote settlements, and the men were compelled to depend entirely upon their rifles for food.

When posts were located at convenient distances from each other in the desolate country where their vocation was carried on, the chances of the trapper for regular meals every day were materially enhanced.

Before the establishment of these rendezvous, where everything necessary for his comfort was kept, and the trapper subsisted on deer, bear meat, buffalo, and wild turkeys — the latter were found in abundance everywhere. He was frequently compelled to resort to dead horses in times of great scarcity. His coffee, and perhaps a scant supply of flour, which he had brought from the last settlement, would rarely suffice until he reached the foot of the mountains, and even when obtainable, the price was so exorbitant that but few of the early adventurers could indulge in such luxuries.

The first trading post was established at the mouth of Clear Creek, Colorado, in 1832 by Louis Vasquez and named Fort Vasquez, after its proprietor, but it never grew into much importance and was soon abandoned.

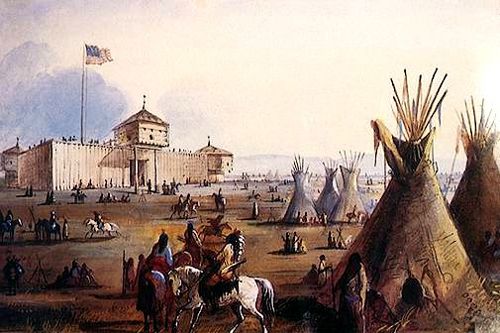

Fort Laramie, Wyoming, one of the most celebrated rendezvous of the trappers, was erected in 1834, by William Sublette and Robert Campbell of St. Louis, agents of the American Fur Company. It was first called Fort William, in honor of Sublette; later Fort John, and finally christened Fort Laramie, after the river which took its name from Joseph Laramie, a French-Canadian trapper of the earliest fur-hunting period, who was murdered by the Indians near the mouth of the river. It was located in the immediate region of the Ogallala and Brule bands of the great Sioux nation and not very remote from that of the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

In 1835, the fort was sold to Milton Sublette, Jim Bridger, and others of the American Fur Company, and the next year, it was rebuilt at $10,000. It remained a private establishment until 1849, the year of the discovery of gold in California, when the government bought and transformed it into a military post to awe the savages who infested the trail to the Pacific, which had then become the great highway of the immense exodus from the Eastern states to the gold regions of that coast.

The original structure was built in the usual style of all Indian trading stations of that day, of adobe, or sun-dried bricks. It was enclosed by walls 20 feet high and four feet thick, encompassing an area 250 feet long by 200 wide. Adobe bastions were erected at the diagonal northwest and southwest corners, commanding every approach to the place.

The number of buildings was twelve in all: there were five sleeping rooms, a kitchen, a warehouse, an icehouse, a meat house, a blacksmith shop, and a carpenter shop. The enclosed corral had a capacity for two hundred animals. The corral was separated from the buildings by a partition, and the area in which the buildings were located was a square, while the corral was a rectangle, into which, at night, the horses and mules were secured. In the daytime, when the presence of Indians indicated the danger of the animals being stolen, they were run into the enclosure.

The roofs of the buildings within the square were close to the walls of the fort and could, if necessary, be utilized as a banquette to repulse any Indian attacks.

The main entrance to the enclosure had two gates, with an arched passage intervening. A small window opened from an adjoining room into this passage so that when the gates were closed, it barred anyone who could still communicate with those within through this narrow aperture. Suspicious characters, especially the Indians, could do their trading without the necessity of being admitted into the fort proper. At times, when an attack by the Indians apprehended danger, the gates were kept shut, and all business was transacted through the window.

When the trade was at its height, about 30 men were usually employed at Fort Laramie, as that station monopolized nearly the entire Indian trade of the whole region tributary to it. There, the famous frontiersmen Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, Jim Baker, Jim Beckwourth, and others, who in those remote times constituted the pioneers of the country’s primitive civilization, made their headquarters.

The officials of the fur companies stationed at Fort Laramie ruled with absolute authority. They were as potent in their sway as the veriest despot, for they had no one to dispute their right to lord it overall. The nearest army outposts were seven hundred miles to the east, and, like the viceroys of Spain after the conquest of Mexico, they were a law unto themselves.

In its palmy days, Fort Laramie, Wyoming, swarmed with women and children whose language, like their complexions, was mixed. All lived almost exclusively on buffalo meat dried in the sun, and their hunters had to go sometimes fifty miles to find a herd of buffalo. After a while, a few domestic cattle were introduced, and the conditions changed somewhat.

No military frontier post in the United States was as beautifully located as Fort Laramie. Surrounded by big bluffs at the intersection of the Laramie and Platte rivers, forming a valley unsurpassed in the fertility of its soil and the richness of its natural vegetation, it was an oasis in the desert. The glory of the once charming place has departed forever. It was abandoned by the government a few years ago, as it was no longer a military necessity, the Indian tribes which it watched having either become tame or removed to far-off reservations.

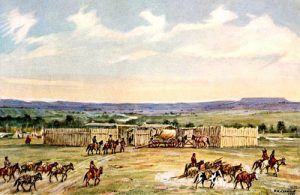

In 1826, Jim Bridger joined General Ashley’s trapping expedition, and eleven years afterward, in 1837, they built Fort Bridger, one of the most famous trading posts for a long time. It was located on the Black Fork of Green River, where that stream branched into three principal channels, forming several large islands, one of which was where the fort was erected. It was constructed of two adjoining log houses with sod roofs, enclosed by a fence of pickets eight feet high, and, as was usual, the offices and sleeping apartments opened into a square, protected from attacks by the Indians by a massive timber gate. Into the corral, all the animals were driven at night to guard them against being stolen or devoured by wild beasts. The fort was inhabited by about fifty whites, Indians, and half-breeds. The fort was the joint property of Bridger and Vasquez. Upon the Mormon occupation of the region, the owners were obliged to abandon it because of disagreements with that sect in 1853.

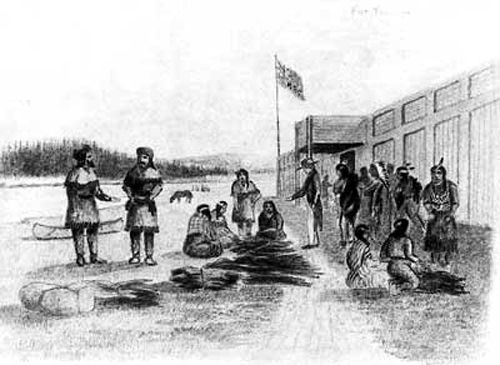

Fort Platte, another trading post belonging to the American Fur Company, was situated about three-fourths of a mile above the mouth of the Laramie River on the left bank of the North Platte and constructed in the same general way described in the preceding paragraphs. As it is natural to suppose, there existed always a desperate rivalry between the two forts. Some of the scenes enacted there long ago are full of blood-curdling adventure and reckless indifference to the preservation of life. The following is a true picture of one of the annual gatherings of the Indian trappers who came there to dispose of their season’s furs more than 50 years ago:

The night of our arrival at Fort Platte was the signal for a grand jollification by all hands, with two or three exceptions, who soon got most gloriously drunk, and such an illustration of the beauties of harmony as was then presented would have rivaled Bedlam itself, or even the famous council-chamber beyond the Styx.

Yelling, screeching, firing, fighting, swearing, drinking, and such like interesting performances were kept up without intermission — and woe to the poor fellow who looked for repose that night. He might have as well thought of sleeping with a thousand cannons booming at his ears.

The scene was prolonged till sundown the next day, and several made their egress from this beastly carousal minus shirts and coats, with swollen eyes, bloody noses, and empty pockets — the latter circumstance will be understood upon the mere mention of the fact that liquor was sold for four dollars a pint!

The enactment of another scene of a comic-tragic character ushered in the day following. The Indians camped in the vicinity, being extremely solicitous to imitate the example of their illustrious predecessors, commenced their demands for fire-water as soon as the first tints of morning began to paint the east. Before the sun had told an hour of his course, they were pretty well advanced in the state of “How come you so?” and seemed to exercise their musical powers in wonderful rivalry with their white brethren.

Men, women, and children were seen running from lodge to lodge with vessels of liquor, inviting their friends and relatives to drink, while whooping, singing, drunkenness, and trading for fresh supplies to administer to the demands of intoxication had evidently become the order of the day. Soon, individuals were seen passing from one another, with mouths full of the coveted fire-water, drawing the lips of favored friends to close contact, as if to kiss, and ejecting the contents of their own into the eager mouths of others — thus affording the delighted recipients tests of fervent esteem in the heat and strength of their strange draught.

At this stage of the game, the American Fur Company, as was charged, commenced to deal out to them gratuitously, strong drugged liquor for the double purpose of preventing the sale of the article by its competitor in trade, and of creating sickness, or inciting contention among the Indians while under the influence of sudden intoxication, hoping thereby to induce the latter to charge its ill effects upon an opposite source, and thus by destroying the credit of its rival to monopolize the whole trade.

It is hard to predict with certainty what would have been the result of this reckless policy had it been continued throughout the day. Already, its effects became apparent, and small knots of drunken Indians were seen in various directions, quarreling, preparing to fight, or fighting, while others lay stretched upon the ground in helpless impotency or staggered from place to place with all the revolting attendants of intoxication.

The drama, however, was brought to a temporary close by an incident that made a strange contrast in its immediate results.

One of the head chiefs of the Brule village, in riding at full speed from Fort John to Fort Platte, being a little too drunk to navigate, plunged headlong from his horse and broke his neck when within a few rods of his destination. Then was a touching display of confusion and excitement. Men and women commenced squalling like children — the whites were bad, very bad, said they, in their grief, to give Susu-Ceicha the fire water that caused his death. But the height of their censure was directed against the American Fur Company, as its liquor had done the deed.

The corpse of the deceased chief was brought to the fort by his relatives with a request that the whites should assist at his burial, but they were in a sorry plight for such a service. Some were found sufficiently sober for the task, however, and accordingly commenced operations.

A scaffold was erected for the reception of the body, which had been fitted for its last airy tenement in the meantime. The duty was performed in the following manner: It was first washed, then arrayed in the habiliments last worn by the deceased during life, and sewed in several envelopes of lodge skin with his bows, arrows, and pipe. This was done, and all things were ready for the proposed burial.

The corpse was borne to its final resting place, followed by a throng of relatives and friends. While moving onward with the dead, the train of mourners filled the air with lamentations and rehearsals of their late chief’s virtues and meritorious deeds.

Arrived at the scaffold, the corpse was carefully reposed upon it facing the east, while beneath its head was placed a small sack of meat, tobacco, and vermilion, with a comb, looking-glass, and knife, and at its feet a small banner that had been carried in the procession. A covering of scarlet cloth was then spread over it, and the body was firmly lashed to its place by long strips of rawhide. This done, the chieftain’s horse was produced as a sacrifice for the benefit of his master in his long journey to the celestial hunting grounds.

The old men, encircling it at a respectful distance, were first seated, followed by the young men and warriors and the women and children. Etespa-huska (The Long Bow), the deceased’s eldest son, commenced speaking, and the weeping throng ceased its tumult to listen to his words.

“O Susu-Ceicha! thy son bemourns thee, even as were wont the fledglings of the war-eagle to cry for the one that nourished them when thy swift arrow had laid him in the dust. Sorrow fills the heart of Etespa-huska; sadness crushes it to the ground and sinks it beneath the sod upon which he treads.

“Thou hast gone, O Susu-Ceicha! Death hath conquered thee, whom none but death could conquer; and who shall now teach thy son to be brave as thou wast brave; to be good as thou wast good; to fight the foe of thy people and acquaint thy chosen ones with the war-song of triumph; to deck his lodge with the scalps of the slain, and bid the feet of the young move swiftly in the dance? And who shall teach Etespa-huska to follow the chase and plunge his arrows into the yielding sides of the tired bull?”

Thus, for half an hour, the young man told of his father’s virtues and great deeds. The moment he had finished, a tremendous howl of grief burst from the whole assemblage, men, women, and children alike. When the wailing ceased, they all returned to their respective lodges.

The sad event of the day put a stop to the Indians’ dissipation, and not long afterward, they commenced to pull down their respective lodges and move to the neighborhood of the buffalo to select their winter quarters.

Two weeks later, a band of Brules arrived in the vicinity of the fort and opened a brisk trade in liquor by indulging in a drunken spree.

The Indians crowded the fort houses seeking articles, soon becoming a terrible nuisance. One room, in particular, was constantly thronged to the exclusion of its regular occupants when the latter, losing all patience with the Indians, adopted the following plan to get rid of them.

After closely covering the chimney with some half-rotten chips, a dense smoke was raised, and the doors and windows were closed at the same time to prevent its escape. In an instant, the apartment became filled to the point of suffocation—too much so for the Indians, who gladly made a precipitate retreat.

They were told it was the “Long-Knife Medicine.” During the visit of the Indians at the fort, a warrior called “Big Eagle” was struck over the head by a half-drunken trader. This incident came very near terminating seriously, but fortunately, it did not. It might have ended in the massacre of all the whites had not some of the more level-headed promptly interfered and, with much effort, succeeded in pacifying the enraged chief by presenting him with a horse.

At first, the Indians would admit to no compromise short of the offender’s blood. The white man had struck him, and blood alone must atone for the aggression. Unless that should wipe out the disgrace, he could never again hold up his head among his people — they would call him a coward and say a white man struck the Big Eagle, and he dared not resent it.

An Indian considers it the greatest indignity to receive a blow from anyone, even from his own brother. Unless the affair is settled by the bestowal of a trespass offering on the part of the aggressor, he is almost sure to seek revenge through blood or the destruction of property. This is more a special characteristic of the Sioux than of any other Indian tribe.

The liquor traffic was a most infamous one, as an abundance of facts could prove.

In November 1855, the American Fur Company from Fort John sent a quantity of their drugged liquor to an Indian village on the Chugwater as a gift to prevent their competitors’ sale of that article in trade. The consequence was that the poor creatures all got beastly drunk, and a fight ensued, in which two chiefs, Bull Bear and Yellow Lodge, and six of their personal friends were murdered. Fourteen others who took part in the fracas were badly wounded. Soon afterward, another affair of the same character occurred and resulted in the death of three of the Indians. Many were killed in quarrels in several Indian villages.

The liquor used in this nefarious trade was generally third or fourth-proof whiskey, which, after being diluted by a mixture of three parts water, was sold to the Indians at the exorbitant rate of three cups for a single buffalo robe, each cup holding about three gills. That was not all: sometimes the cup was not more than half-filled; then again, the act of measuring was also a rascally transaction, for when the poor Indians became so drunk that he could not see, he was cheated — more water was added, the unlucky purchaser not receiving more than one-fourth of what he paid for. There were still other modes of cheating.

To further show how demoralizing the traffic was, I will relate an instance: “Old Bull Tail,” a chief of the Sioux, had an only daughter named Chint-zille. She was very handsome, as savage beauty goes. The old chief really loved her, for the North American Indian is possessed of as much devotion to his family as is to be found in the most cultivated of the white race. Still, the old fellow was inordinately fond of getting drunk and, at one time, not having the wherewithal to procure the necessary liquor, made up his mind that he would trade his daughter for a sufficient quantity.

One morning, he entered a trader’s store, accompanied by Chint-zille. The following dialogue took place:

“Bull Tail is welcome to the lodge of the Long-Knife, but why is his daughter, the pride of his heart, bathed in tears? It pains me that one so beautiful should weep.”

The old chief answered: “Chint-zille is a foolish girl. Her father loves her, and therefore she cries.”

“There should be greater cause for grief than that.”

“The Long-Knife speaks well.”

“How then can she sorrow? Tell her to speak to me, that I may whisper words of comfort in her ear.”

“I will tell you, Long-Knife: Bull Tail loves his daughter very much; he loves Long-Knife very much! he loves them both very much. The Great Spirit has put the thought into his mind that both alike might be his children; then would his heart leap for joy at the twice-spoken name of father!”

“I do not understand the meaning of Bull Tail’s words.”

“Sure, Long-Knife, you are slow to understand! Bull Tail would give his daughter to the Long-Knife. Does not Long-Knife love Chint-zille?”

“If I should say no, my tongue would lie; Long-Knife has no wife, and who, like the lovely Chint-zille, is so worthy that he should take her to his bosom? How can I show my gratitude to her noble father?”

“The gift is free, and Bull Tail will be too glad in its acceptance; his friends will all be glad with him. But that they may bless the Long Knife, let him fill up the hollow wood with fire-water, and Bull Tail will take it to his lodge; then Chint-zille will be yours.”

“But Chint-zille grieves; she does not love the Long-Knife.”

“Chint-zille is foolish. Let the Long Knife measure the fire water, and she shall be yours.”

“No, Long-Knife will not do this; Chint-zille should never be the wife of the man she does not love.”

The old chief pleaded for a long time with the trader to take the girl and give him the liquid, but the trader was inexorable; he would not form any such tangling alliance, so the old chief failed to get the liquor, and he left the house with mortification and shame depicted on his withered face.

By H. Inman and W.F. Cody, 1898. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

Old West Explorers, Trappers, Traders & Mountain Men

Trading Posts of the Fur Trade

Notes and Authors: This article was excerpted from the book The Great Salt Lake Trail, written by Colonel Henry Inman and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and first published in 1898. (now in the public domain.) Inman was an officer in the U.S. Army and an author dealing with subjects of the Western plains. Buffalo Bill was a buffalo hunter, scout, and showman. The article that appears on these pages is not verbatim, as it is edited for spelling, grammatical corrections, and ease of the modern reader.