In the Wild West, the harsh Puritan sanctions were not as “practical” as in America’s more conservative eastern counterpart. And though the “proper” ladies still labeled those who didn’t share their values — by dress, behavior, or sexual ethics, as “disgraceful,” the shady ladies of the West were generally tolerated by other women as a “necessary evil.”

California ‘49ers labeled these women with names such as “ladies of the line” and “sporting women,” while the cowboys dubbed them “soiled doves.” Among the many trails of Kansas, common terms included “daughters of sin,” “fallen frails,” “doves of the roost,” and “nymphs du prairie.” Other nicknames for these women, who were as much a part of the Old West as were the outlaws, cowboys, and miners, were “scarlet ladies,” fallen angels,” “frail sisters,” “fair belles,” and “painted cats,” among dozens of others.

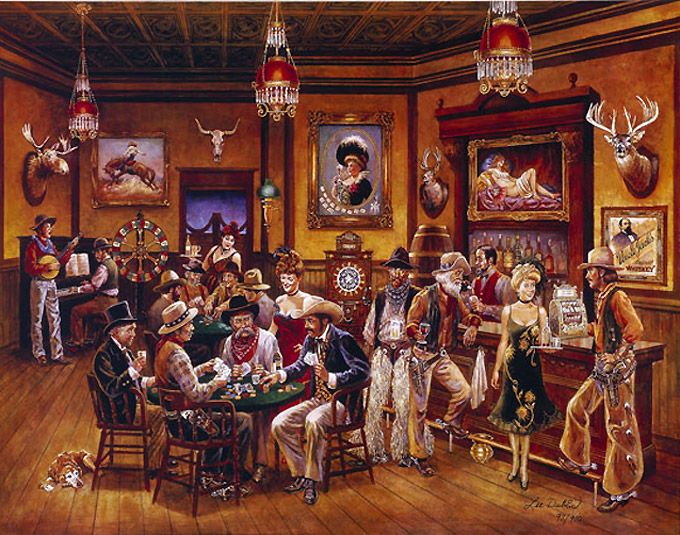

The biggest difference in the American West was the presence of girls in saloons.

This was unheard of east of the Missouri River, except in German beer halls, where the daughters or wives of the owners often served as barmaids and waitresses.

There were two types of “bad girls” in the West. The “worst” types, according to the “proper” women, were the many painted ladies who made their living by offering paid sex in the numerous brothels, parlor houses, and cribs of the western towns. The second type of “bad girl” was the saloon and dance hall women, who, contrary to some popular thinking, were generally not prostitutes — this tended to occur only in the very shabbiest class of saloons. Though the “respectable” ladies considered the saloon girls “fallen,” most of these women wouldn’t be caught dead associating with an actual prostitute.

Saloon and Dance Hall Girls

A saloon or dancehall girl’s job was to brighten the evenings of the many lonely men of the western towns. In the Old West, men usually outnumbered women by at least three to one – sometimes more, as was the case in California in 1850, where 90% of the population was male. Starved for female companionship, the saloon girl would sing for the men, dance with them, and talk to them – inducing them to remain in the bar, buying drinks, and patronizing the games.

Not all saloons employed saloon girls, such as in Dodge City’s north side of Front Street, which was the “respectable” side, where both saloon girls and gambling were barred and featured music and billiards as the chief amusements to accompany drinking.

Most saloon girls were refugees from farms or mills, lured by posters and handbills advertising high wages, easy work, and fine clothing. Many were widows or needy women of good morals, forced to earn a living in an era that offered few means for women to do so.

Earning as much as $10 per week, most saloon girls also made a commission from the drinks they sold. Whiskey sold to the customer was generally marked up 30-60% over its wholesale price. Commonly drinks bought for the girls would only be cold tea or colored sugar water served in a shot glass; however, the customers were charged the full price of whiskey, which could range from ten to seventy-five cents a shot.

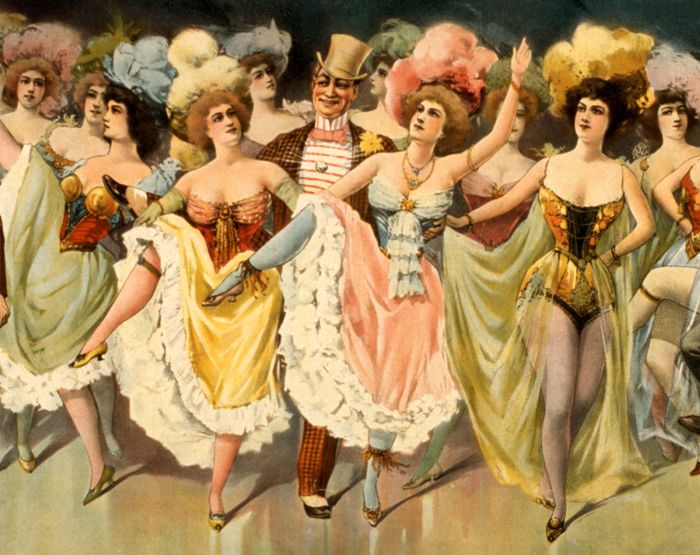

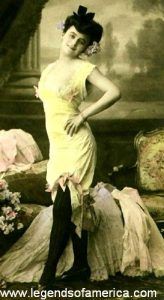

Saloon girls wore brightly colored ruffled skirts that were scandalously short for the time – mid-shin or knee-length. Under the bell-shaped skirts could be seen colorfully hued petticoats that barely reached their kid boots that were often adorned with tassels. More often than not, their arms and shoulders were bare, their bodices cut low over their bosoms, and their dresses decorated with sequins and fringe. Silk, lace, or net stockings were held up by garters, which were often gifts from their admirers. The term “painted ladies” was coined because the “girls” had the audacity to wear make-up and dye their hair. Many were armed with pistols or jeweled daggers concealed in their boot tops or tucked between her breasts to keep the boisterous cowboys in line.

Most saloon girls were considered “good” women by the men they danced and talked with, often receiving lavish gifts from admirers. In most places, the proprieties of treating the saloon girls as “ladies” were strictly observed, as much because Western men tended to revere all women as because the women or the saloon-keeper demanded it. Any man who mistreated these women would quickly become a social outcast, and if he insulted one, he would very likely be killed.

And, as for the “respectable women,” the saloon girls were rarely interested in the opinions of the drab, hard-working women who set themselves up to judge them. In fact, they were hard-pressed to understand why those women didn’t have enough sense to avoid working themselves to death by having babies, tending animals, and helping their husbands try to bring in a crop or tend the cattle.

In the early California Gold Rush of 1849, dance halls began to appear and spread throughout later settlements. While these saloons usually offered games of chance, their chief attraction was dancing. The customer generally paid 75¢ to $1.00 for a ticket to dance, with the proceeds being split between the dance hall girl and the saloon owner. After the dance, the girl would steer the gentleman to the bar, where she would make an additional commission from selling a drink.

Dancing usually began about 8:00 p.m., ranging from waltzes to schottisches, with each “turn” lasting about 15 minutes. A popular girl would average 50 dances a night, sometimes making more a night than a working man could make in a month. Dancehall girls made enough money that it was very rare for them to double as a prostitute; in fact, many former “soiled doves” found they could make more money as dancehall girls.

The dance girls were a profitable commodity to the saloon owner, and gentlemen were discouraged from paying too much attention to any one girl, as dancehall owners lost more women to marriage than in any other way.

Though most patrons respected the girls, violent deaths were one of their biggest professional hazards. More than a hundred cases were documented, but there were, no doubt, probably many more. One saloon girl, who was savagely beaten, had repelled the advances of a drunken customer. When a cowboy approached her, she responded: “I don’t mind the black eye, but he called me a whore.”

The Real Shady Ladies

Some of the reasons why women entered prostitution during the Wild West are probably not a lot different than it is today. However, with limited opportunities in the nineteenth century, many had little choice when they were abandoned by their husbands or stranded in Old West towns when their spouse was killed. Some just had no other skills to provide a means of support. Others were the daughters of prostitutes, already tainted in the business. The saddest reason was that women were seduced by a cad, lost their virginity, or were raped. At the time, these women were seen as “lost,” and there was no hope for them, virtually forcing them into prostitution.

Though the “proper” ladies ignored the existence of brothels, realistically, they admitted their necessity to distract the attention of men from pursuing their daughters and relieving them of their “obligation.”

The Old Homestead was the most popular house in Cripple Creek, Colorado, during its heyday. Pearl de Vere, its famous madam, sometimes charged as much as $1,000 to entertain the men of the district. Today, it continues to stand as a museum. By Kathy Weiser-Alexander.

At the time, Victorian prudence had long taught “decent” women that the sexual act was solely to bear children. She was taught that she shouldn’t respond in any way and that her man should be indulged from time to time, but best to be avoided whenever possible.

The men of the West were often intimidated by the “decent” women who laid down the moral law and found themselves much more comfortable with the painted ladies who allowed them to be who they were.

Virtually every Old West town had at least a couple of “shady ladies” who were the source of much gossip. Sometimes she would “hide” behind the chore of taking in the laundry as a seamstress or running a boarding house. But, often, she would flaunt her profitable bordello by prancing through the streets in her fine clothing, much to the chagrin of the “proper” women of the town. Such was the case of Pearl de Vere of Cripple Creek, Colorado.

By the 1860s, prostitution was a booming business. Though it was illegal almost everywhere, it was impossible to suppress, so the law generally did little more than try to confine the parlors and brothels to certain districts of the community. Others regularly fined the brothels and painted ladies as a type of taxation. But otherwise, the businesses thrived with little intervention from the law.

Shady Ladies were so numerous in some frontier towns that some historians have estimated that they made up 25% of the population, often outnumbering the “decent” women 25 to 1. As the Old West towns grew, they often had several bordellos staffed by four or five women. Usually, painted ladies were between the ages of 14 and 30, with an average age of 23.

Some high-class courtesans often demanded as much as $50 from their clients; however, rates on the frontier generally ranged from $5 at nicer establishments to $1 or less for most ladies of the night. Sometimes they would split their earnings with the madam of the parlor house, while others paid a flat fee per night or week.

As in most occupations, there was a pecking order, with the women who lived in the best houses at the top and scorning those who worked out of dance halls, saloons, or “cribs.” However, the majority of prostitutes did work out of parlor houses, the best of which looked like respectable mansions. To advertise the building’s true intent, red lanterns were often hung under the eaves or beside the door, and bold red curtains adorned the lower windows. Inside, there was usually a lavishly decorated parlor, hence the name “parlor house.” The walls were flanked with sofas and chairs, and often a piano stood in attendance for girls who might play or sing requests for customers.

The larger places were likely to include a game room and a dance hall. Between assignations, the women and their callers were entertained by musicians, dancers, singers, and jugglers.

The most successful landladies maintained, at least on the ground floor, a strict air of respectability and a charming home life. They also insisted that their girls wear corsets downstairs and forbade “rough stuff.”

Every house had a bouncer to handle customers who got too rough with the girls who didn’t want to pay their bill. This is likely one of the reasons the girls considered themselves superior to those who worked independently.

The girls’ rooms were always on the second floor if there was one. Parlor houses usually averaged six to 12 girls, plus the madam, who entertained only those customers she personally selected. First-class places set a good table and prided themselves on their cellars, offering choice cigars, bonded bourbon, and the finest liquors and wines. Customers could enjoy champagne suppers and sing with the girls around the piano. In very high-class parlor houses, the women could only be seen by appointment.

The women usually sent East for their finery or bought it from passing peddlers. Their gowns were generally tight, snugging them at the hips, slit to the knee on one side with deep décolletage, and decorated with sequins or fringe. In mining towns, the “girls” were often seen walking, riding, or in carriages, dressed in their eye-catching finery.

The lower grade of bordello came to be called a “honkytonk” from a common southern African-American term.

In these houses, there was very little subtlety. The direct approach was standard, with maybe a five-minute dalliance at the bar, then it was off to her room.

Lower than even the saloon prostitutes were those who worked independently, living in small houses or cabins called cribs. Crib houses were usually in segregated districts with a front bedroom and a kitchen in the rear. Often they were illuminated by red lamps and or curtains. Some madams kept a string of “cribs” available for women no longer employable within the house, continuing to profit from the older painted ladies.

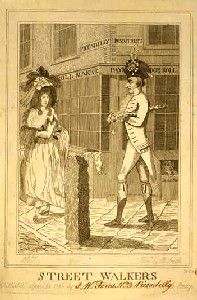

Below even those were the streetwalkers, usually only found in the larger cities.

Below even those were the streetwalkers, usually only found in the larger cities.

In a class by themselves were the women who serviced the military at remote forts. Many settlements that grew up around a fort were not large enough to support a “decent” parlor house, and most self-respecting madams would not admit a lowly-paid soldier anyway. Before long, a district referred to as “Hog Town” could usually be found near these remote forts. Here, the soldiers could find gambling, whiskey, and a few aging and degenerate women.

Black men were not allowed to patronize white brothels, but many towns had all-black houses. And in a few small towns, some houses had black and white women.

Though it may seem odd, many “painted ladies” were married, some to saloon owners or brothel operators. Others were married to managers of touring variety shows. Such men tolerated the profession and depended on their wives to help with the finances.

Inevitably, painted ladies had children, though attempts were made at birth control which was very primitive at the time. By the 1840s, women could purchase Portuguese Female Pills (an abortion pill) or Madame Restell’s Preventive Powders, but it is unclear how effective these were. The French had already invented the condom, fashioned of rubber or skin, as they are today. In places like New Orleans or St. Louis, where there was a large French population, condoms were readily available. However, much like today, many men were reluctant to use them. After 1860 diaphragms were available, and douches compounded from ingredients such as alum, pearlash, red rose leaves, carbolic acid, bicarbonate of soda, sulfate of zinc, vinegar, or plain water. Others simply relied on the rhythm method.

But, the most common form of birth control was abortion, which had also spread as a form of birth control to even “respectable women.” In the years between 1850 and 1870, one historian estimated that one abortion was performed for every five to six live births in America.

If they were lucky, a courtesan would marry well and retire with enough money for a comfortable and respectable lifestyle. Those who married would normally become instantly “respectable” as it was considered impolite in the Old West to ask for a person’s background, and most people were too busy to care. Others used their profits to open their own sporting houses, became saloon operators, or practiced as abortionists. Inevitably though, some often turned to alcohol or narcotics – dosing their drinks with laudanum or smoking opium. Suicides were frequent in the profession.

Women on the line were often in peril of picking up tuberculosis, called consumption at the time, or sexually transmitted diseases, chiefly syphilis. Others died as a result of botched abortions, sometimes self-inflicted. Violence also claimed its share in brawls between prostitutes, customers, and sometimes, husbands.

Another fun video from our friends at Arizona Ghostriders.