By Emerson Hough in 1905

The entire history of the American frontier is one of rebellion against the law, if, indeed, that may be called rebellion whose apostles have not yet recognized any authority of the law. The frontier antedated anarchy. It broke no social compact, for it had never made one. Its population asked for no protection save that afforded under the stern lordship of the six-shooter. The anarchy of the frontier, if we may call it such, was sometimes little more than self-interest against self-interest. This was the true description of this border conflict.

The Lincoln County War embraced three wars: the Pecos War of the early 1870s, the Horrell War of 1874, and the Lincoln County War proper, which may have begun in 1874 and ended in 1879.

The actors in these different conflicts were all intermingled. There was no blood feud at the bottom of this fight. It was a war of self-interest against self-interest, with each side supported by numerous fighting men.

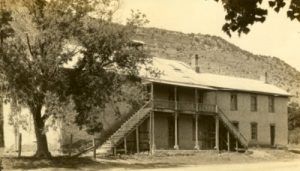

At that time, Lincoln County, New Mexico, was about as large as Pennsylvania. For judicial purposes, it was annexed to Donna Ana County. Its territories included both the present counties of Eddy and Chaves and part of what is now Donna Ana County. It extended west practically as far as the Rio Grande and embraced a tract of mountains and high tableland nearly two hundred miles square. Out of this mountain chain, to the east and southeast, ran two beautiful mountain streams, the Bonito and the Ruidoso, flowing into the Hondo River, which continues to the flat valley of the Pecos River — once the natural pathway of the Texas cattle herds bound north to Utah and the mountain territories, and hence the natural pathway also for many lawful or lawless citizens from Texas.

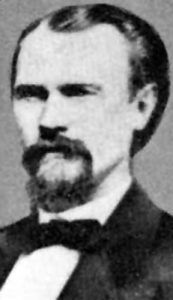

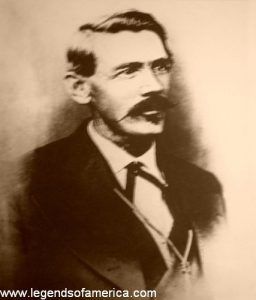

At the close of the Civil War, Texas was full of unbranded and unowned cattle. Out of Paris, Texas, which his father founded, came John Chisum—one of the most typical cowmen ever. Bold, fearless, shrewd, unscrupulous, genial, and magnetic, he was the man of all others to occupy a kingdom with no ruler.

John Chisum.

John Chisum drove the first herds up the Pecos Trail to the territorial market. At one time, he held perhaps 80,000 head of cattle under his brand of the “Long I” and “jinglebob.” Moreover, he had powers of attorney from many cowmen in Texas and lower New Mexico, authorizing him to take up any trail cattle he found under their respective brands. He carried a tin cylinder, large as a waterspout, that contained, some said, more than a thousand of these powers of attorney. At least, it is certain he had papers enough to give him a broad authority. Chisum riders combed every north-bound herd. If they found the cattle of any of his “friends,” they were cut out and turned on the Chisum range. There were many “little fellows,” small cattlemen, nested here and there on the flanks of the Chisum herds.

What’s more natural than that they should steal from him if they found a market of their own? That was much easier than raising cows on their own. There was a market up this winding Bonito Valley at Lincoln and Fort Stanton, New Mexico. The soldiers of the last post and the Indians of the Mescalero Reservation nearby needed supplies. Others besides John Chisum might need a beef contract now and then and cattle to fill it.

At the end of the Civil War, there was what was known as the California Column in New Mexico, which joined the forces of New Mexican Volunteers, an officer known as Major Lawrence G. Murphy. After the war, many men settled near the points where they were mustered out in the South and West. It was thus with Major Murphy, who was a post-trader at the little frontier post known as Fort Stanton, founded by Captain Frank Stanton in 1854 in the Indian days.

John Chisum located his Bosque Grande Ranch about 1865, and Murphy came to Fort Stanton about 1866. In 1875, Chisum dropped down to his South Spring River Ranch, and by that time, Murphy had been thrown out of the post-tradership by Major Clendenning, commanding officer, who did not like his methods. He had dropped nine miles down the Bonito River from Fort Stanton with two young associates under the firm name of Murphy, Riley & Dolan, sometimes spoken of as L.G. Murphy & Co.

Murphy was a hard-drinking man, yet withal something of a student. He was intelligent, generous, bold, and shrewd. He “staked” every little cowman in Lincoln County, including many who hung on the flanks of John Chisum’s herds. These men, in turn, were, in their ethics, bound to support him and his methods. Murphy was king of the Bonito country. Chisum was king of the Pecos, not a merchant but a cowman, and cared for nothing with no grass or water.

Here, then, were two rival kings. Each at times had occasion for a beef contract. The result is obvious to anyone who knows the ways of the remoter West in earlier days. The times were ripe for trouble. As the government records show, Murphy bought stolen beef and furnished bran instead of flour on his Indian contracts. His henchmen held the Chisum herds as their legitimate prey. Thus, we now have our stage set and peopled for the grim drama of a bitter border war.

The Pecos War was mostly an indiscriminate killing among cowmen and cattle thieves, and it cost many lives, though it had no beginning and no end. For the most part, the Texas men, hard riders, and cheerful shooters came pushing up the Pecos River and into the Bonito Canyon. Among these, in 1874, were four brothers known as the Horrell boys, Bill, Jack, Tom, and Bob, who had come from Texas in 1872. Two of them located ranches on the Ruidoso, being “staked” therein by Major Murphy, king for that part of the countryside.

The Horrell boys once undertook to run the town of Lincoln, and a foolish justice ordered a constable to arrest them. Jack Gylam, an ex-sheriff, told the boys to put on their guns. Gylam, Bill Horrell, Dave Warner, and Martinez, the Mexican constable, were killed on that night. The dead body of Martinez was lying in the street the next morning with a deep cross-cut on the forehead. From that time on, it was no uncommon thing to see dead men lying in the streets of Lincoln for the next five years. The Horrell boys had sworn revenge.

There was a little dance in an adobe one night at Lincoln when Ben Horrell and some Texas men from the Seven Rivers country rode up. They killed four men and one woman that night before going back to Seven Rivers. From then on, it was Texas against the law, such as the latter. No resident places the number of the victims of the Horrell War at less than 40 or 50, and it is believed that at least 75 would be more correct. These killings proved the weakness of the law, for none of the Horrell gang was ever punished. As for the Lincoln County War proper, the magazine was now handsomely laid. Only the spark was needed. What would that naturally be? Either an actual law court or else — a woman! In due time, both were forthcoming.

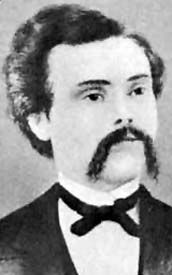

Susan McSween.

The woman in the case still lived in New Mexico in the early 1900s, sometimes called the “Cattle Queen” of New Mexico. At that time, she bore the name of Mrs. Susan E. Barber. Her maiden name was Susan E. Hummer, and she was born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Susan Hummer was the granddaughter of Anna Maria Spangler-Stauffer. The Spangler family is a noble one in Germany and very old. George Spangler was cup-bearer to Godfrey, Chancellor of Frederick Barbarossa, and was with the latter on the Crusade when Barbarossa was drowned in the Syrian river, Calycadmus, in 1190. The American seat of this old family was in York County, Pennsylvania, where the first Spanglers settled in 1731. From this tenacious and courageous ancestry, this figure of border warfare sprang in a region wild as Barbarossa’s realm centuries ago.

On August 23, 1873, in Atchison, Kansas, Susan Hummer married Alexander A. McSween, a young lawyer fresh from the Washington University Law School of St. Louis, Missouri. McSween was born in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, and was educated in the first place as a Presbyterian minister.

He was a man of good appearance, intelligence, and address, and he was rather more polished than the average man. He was an orator, a dreamer, and a visionary, a strange, complex character. He was not a fighting man and belonged anywhere in the world rather than on the frontier of the bloody Southwest. His health was not good, and he fled to New Mexico. He and his young bride started overland with a good team and conveyance and reached Lincoln in the Bonito Canyon on March 15, 1875. Outside of Murphy, Riley & Dolan, only one or two other American families were in the area at that time. McSween started up in the practice of law.

There appeared in northern New Mexico at about this time, an Englishman named John H. Tunstall, newly arrived in the West in search of investment. Tunstall was told that Lincoln County had a good open cattle range. He came to Lincoln, met McSween, formed a partnership with him in the banking and mercantile business, and started for himself, and altogether independently, a horse and cattle ranch on the Rio Feliz, a day’s journey below Lincoln. King Murphy of Lincoln County found a rival business growing up directly under his eyes. He liked this no better than King Chisum liked the little cowmen on his flanks in the Seven Rivers country. Things were ripening still more rapidly for trouble. Presently, the immediate cause made its appearance.

There had been a former partner and friend of Major Murphy in the post-tradership at Fort Stanton, Colonel Emil Fritz, who established the Fritz Ranch a few miles below Lincoln. Having amassed a considerable fortune, Colonel Fritz decided to return to Germany. He had insured his life in the American Insurance Company for $10,000 and had made a will leaving this policy, or the greater part of it, to his sister. The latter had married a clerk at Fort Stanton named Scholland but did not get along well with her husband. Heretofore, no such thing as divorce had been known in that part of the world, but courts and lawyers were now present, and it occurred to Mrs. Scholland to have a divorce. She was sent to McSween for legal counsel and lived in the McSween house for a time.

Now came news of Colonel Emil Fritz’s death in Germany. His brother, Charlie Fritz, undertook a look at the estate. He found the will and insurance policy had been left with Major Lawrence Murphy. Still, Major Murphy, accustomed to running affairs in his way, refused to give up Emil Fritz’s will and forced McSween to get a court order appointing Mrs. Scholland, administrator of the Fritz estate. Not even in that capacity would Major Murphy deliver to her the will and insurance policy when they were demanded, and it is claimed that he destroyed the will. Certainly, it was never probated. Murphy was accustomed to keeping this will in a tin can, hidden in a hole in the adobe wall of his store building. There were no safes at that time and place. The policy had been left as security for a loan of nine hundred dollars advanced by a firm known as Spiegelberg Brothers. Few ingredients were now lacking for a typical melodrama. In the meantime, the plot thickened by the insurance company’s failure!

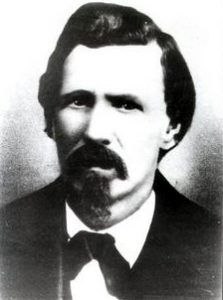

Alexander McSween.

McSween, in the interest of Mrs. Scholland, now went East to see what could be done to collect the insurance policy. He was finally able, in 1876, to collect the total amount of $10,000, which he deposited in his name in a St. Louis, Missouri bank then owned by Colonel Hunter. He had been obliged to pay the Spiegelbergs the face of their loan before he could get the policy to take East with him. He wished to be secured against this advancement and reimbursed as well for his expenses, which, together with his fee, amounted to a considerable sum. Moreover, the German Minister enjoined McSween from turning over any of this money, as there were other heirs in Germany. Major Murphy owed McSween some money. Colonel Fritz also died owing McSween thirty-three hundred dollars, fees due on legal work. Yet, Murphy demanded the full amount of McSween’s insurance policy again and again. Murphy, Riley & Dolan now sued out an attachment on McSween’s property and levied on the goods in the Tunstall-McSween store. The “law” was now working, but a very liberal interpretation was put upon its intent. As construed by Sheriff William Brady, the writ also applied to the Englishman Tunstall’s property in cattle and horses on the Rio Feliz Ranch, which was high-handed illegality. McSween’s statement that he had no interest in the Feliz Ranch served no purpose. Brady and Murphy were warm friends. The lawyer McSween had accused them of being something more than that — allies and conspirators. McSween and Tunstall bought Lincoln County scrip cheap, but when they presented it to the county treasurer, Murphy, it was not paid, and it was charged that he and Brady had made away with the county funds. That was never proven, for no county books were ever kept! McSween started the first set ever known there.

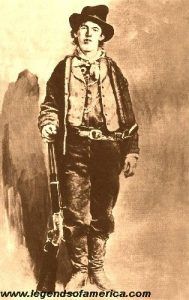

There was working for Tunstall on the Feliz Ranch, the noted desperado, Billy the Kid, who formerly worked for John Chisum for a short time. At this stage of the advancing troubles, the latter appears rather as a third party or as holding one point of a triangle, whose other two corners were occupied by the Murphy and McSween factions.

Whether or not it was a legal posse that went out to serve the attachment on the Tunstall cattle — or whether or not a posse was necessary for that purpose — the truth is that a band of men, on February 13, 1878, did go out under some semblance of the law and in the interests of the Murphy people’s claim. Some state that William S. Morton, or “Billy” Morton, was chosen by Sheriff Brady as his deputy and as leader of this posse. Others name different men as leaders. Indeed, the band was suited for any desperate occasion. With it was Tom Hill, who had killed several men at different times and had been heard to say that he intended to kill Tunstall. There was also Jesse Evans, just in from the Rio Grande country, and, except for Billy the Kid, was the most redoubtable fighter in all that country. Evans had formerly worked for John Chisum and had been the friend of Billy the Kid, but these two had now become enemies. Others of the party were William M. Johnson, Ham Mills, Johnnie Hurley, Frank Baker, several ranchers still living in that country, and two or three Mexicans. All these rode across the mountains to the Ruidoso Valley and Rio Feliz.

They met, coming from the Tunstall ranch, Tunstall himself in company with his foreman, Dick Brewer, John Middleton, and Billy the Kid. When the Murphy posse came up with Tunstall, he was alone. His men were at the time chasing a flock of wild turkeys along a distant hillside. When called upon to halt, Tunstall did so and came up toward the posse. “You wouldn’t hurt me, boys, would you?” he said as he approached, leading his horse. When within a few yards, Tom Hill said to him, “Why, hello, Tunstall, is that you?” and almost with the words fired upon him with his six-shooter and shot him down. Some say that Hill shot Tunstall again, and a young Mexican boy called Pantilon beat his skull with a rock. They put Tunstall’s hat under his head and left him lying there beside his horse, which was also killed. His folded coat was found under the horse’s head. His body lashed on a burro’s back, was brought over the mountains that night into Lincoln, 20 miles distant. Fifty men took up the McSween fight that night, for, in truth, the killing of Tunstall was murder and without justification.

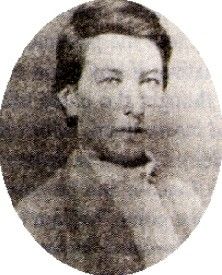

Richard “Dick” Brewer.

That was the beginning of the actual Lincoln County War. Dick Brewer, Tunstall’s foreman, was now the leader of the McSween fighting men, known as the Regulators. McSween, of course, supplied him with the color of “legal” authority. He was appointed “special constable.” Neither party had difficulty in obtaining all the legal papers required. Each party was presently to have a sheriff of its own. In the meantime, there was an accommodating justice of the peace at Lincoln, and John P. Wilson was ready to give either faction any legal paper it demanded. Dick Brewer, Billy the Kid, and nearly a dozen others of the first McSween posse started to the lower country, where many of Murphy’s friends, small cowmen, and others lived there. On the Rio Peñasco, about six miles from the Pecos, they came across a party of five men, two of whom, Billy Morton and Frank Baker, had been present at the killing of Tunstall. Baker and Morton surrendered under the promise of safekeeping and were held for a time at Roswell. On the trail from Roswell to Lincoln, at a point near the Agua Negra, both these men, while kneeling and pleading for their lives, were deliberately shot and killed by Billy the Kid. A buffalo hunter named McClosky with the Brewer posse promised to care for these prisoners. Frank MacNab, of the posse, shot and killed McClosky in cold blood. In this McSween posse were “Doc” Scurlock, Charlie Bowdre, Billy the Kid, Henry Newton Brown, Jim French, John Middleton, with MaNab, Wait, and Smith, besides McClosky, who seems not to have been loyal enough to them to sanction cold-blooded murder. These victims were killed on March 7, 1878.

There had now been deliberate murder committed upon the one side and the other. There were many men implicated on each side. These men, in self-interest, now drew apart together. The factions, of necessity, became more firmly established. It may be seen that there was very little principle at stake on either side. The country was now simply going wild again. It meant to take the law into its own hands, and the population was divided into these two factions, to one or the other of which every resident must perforce belong. A choice, and sometimes a quick one, was an imperative necessity.

The next killing was that of Buckshot Roberts at Blazer’s Mill, near the Mescalero Reservation buildings, an affair described in a later chapter. Thirteen men, later of the Kid’s gang, led by Dick Brewer, attacked Roberts, who killed Dick Brewer before he himself died. The death of the latter left the Kid chief of the McSween forces.

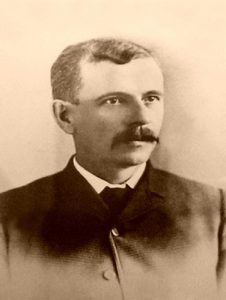

A great bloodlust now possessed all the population. It wanted no law. There is no doubt about the intention to make away with Judge Warren Bristol of the circuit court. Knowing of these turbulent times in Lincoln, the latter decided not to hold court. He sent word to Sheriff William Brady to open court and then at once to adjourn it. This was on April 1, 1878.

Walking down the street toward the dwelling-house where court sessions were held, Sheriff Brady was obliged to pass the McSween store and residence. Behind the corral wall, there lay ambushed Billy the Kid and at least five others of his gang. Brady was accompanied by Billy Matthews, George Hindman, his deputy, and George Peppin, later sheriff of Lincoln County. The Kid and his men waited until the victims had gone by. Then, a volley was fired. Sheriff Brady, shot in the back, slowly sank down, his knees weakening under him. “My God! My God! My God!” he exclaimed as he gradually dropped. He had been struck in the back by five balls. As he sank down, he turned his head to see his murderers and, as he did so, received a ball in the eye and so fell dead. George Hindman, the deputy, also shot in the back, ran down the street about 150 yards before he fell. He lay in the street, and few dared to go out to him. A saloon keeper, Ike Stockton (himself a bad man and later killed at Durango, Colorado), offered him a drink of water, which he brought in his hat, and Hindman, accepting it, fell back dead.

William J. Brady.

The murder of Sheriff Brady left the country without even the semblance of law, but each party now took steps to set up legal machinery of its own as cover for its own acts. The old justice of the peace, John P. Wilson, would issue a warrant on any pretext for any person, but there must be someone with authority to serve the process. In a quasi-election, the McSween faction instituted John Copeland as their sheriff. The Murphy faction held that Copeland never qualified as sheriff. He lived with McSween for part of the time. It was understood that he was sheriff to bother nobody but the Murphy people.

In the meantime, the other party was not thus to be surpassed. In June 1878, Governor Axtell appointed George W. Peppin as sheriff of Lincoln County. Peppin qualified at Mesilla, returned to Lincoln, and demanded Copeland to hold the warrants in his possession. He had, on his part, 12 warrants for the arrest of members of the Regulators. Little lacked now to add confusion in this bloody coil. The country was split into two factions. Each had a sheriff as a figurehead! What and where was the law?

Peppin had to get fighting men to serve his warrants, and he could not always be particular about the social standing of his posses. He had a thankless and dangerous position as the “Murphy sheriff.” Most of his posses were recruited from among the small ranchers and cowboys of the lower Pecos. Peppin was sheriff only a few months and threw up the job for $2,800 in debt.

The men of both parties were now scouting about for each other here and there over a district more than a hundred miles square, but presently, the war was to take on the dignity of a pitched battle.

Early in July 1878, the Kid and his gang rounded up at the McSween house. There were a dozen white desperadoes in their party. There were about forty Mexicans also identified with the McSween faction. These were quartered in the Montana and Ellis residences well down the street.

The Murphy forces now surrounded the McSween house, and a pitched battle began at once. The McSween men started firing from the windows and loopholes of their fortress. The Peppin men replied. The town, divided against itself, held undercover. For three days, the two little armies lay here, separated by the distance of the street, perhaps sixty men in all on the McSween side, perhaps thirty or forty in all on the Murphy-Peppin side, of whom 19 were Americans.

To keep the McSween men inside their fortifications, Peppin had three men posted on the mountainside, whence they could look down directly upon the top of the houses as the mountain here rises up sharply back of the narrow line of adobe buildings. These pickets were Charlie Crawford, Lucillo Montoye, and another Mexican, and with their long-range buffalo guns, they threw a good many heavy slugs of lead into the McSween house. At last, one Fernando Herrera, a McSween Mexican standing in the back door of the Montana House, fired, at a distance of about nine hundred yards, at Charlie Crawford. The shot cut Crawford down, and he lay, with his back broken, behind a rock on the mountainside in the hot sun nearly all day. Crawford was later brought down to the street. There was no medical attendance, and few dared to offer sympathy, but Captain Saturnino Baca carried Crawford a drink of water.

Tom “Big Foot” O’Folliard.

The death of Crawford ended the second day’s fighting. Peppin’s party now numbered sixteen men from the Seven Rivers country or twenty-eight in all. The McSween men besieged in the adobe were Billy the Kid, Harvey Norris (killed), Tom O’Folliard, Ighenio Salazar (wounded and left for dead), Ignacio Gonzales, José Semora (killed), Francisco Romero (killed), and Alexander McSween, leader of the faction (killed). Doc Scurlock, John Middleton, and Charlie Bowdre were in the adjoining store building.

At about noon of the third day, old Andy Boyle, ex-soldier of the British army, said, “We’ll have to get a cannon and blow in the doors. I’ll go up to the fort and steal a cannon.” Halfway up to the fort, he found his cannon — two Gatlin guns and a troop of colored cavalry — already on the road to stop what had been reported as firing on women and children. The detachment was under the charge of the commanding officer of Fort Stanton, Colonel Dudley, who marched his men past the beleaguered house and drew them up below the place. Mrs. McSween pleaded with Colonel Dudley, who came out under fire to save her husband’s life, but he refused to interfere or take a side in the matter, saying that the county sheriff was there and in charge of his own posse. Mrs. McSween refused to accept protection and go up to the post but returned to her husband for what she knew must soon be the end.

McSween, ex-minister, lawyer, honest or dishonest instigator, innocent or malicious cause — and one may choose his adjectives in this matter — of all these bloody scenes, now sat in the house, his head bowed in his hands, the picture of foreboding despair. His nerve was absolutely gone. No one paid any attention to him. His wife, the actual leader, was far braver than he. The Kid was the commander. “They’d kill us all if we surrendered,” he said. “We’ll shoot it out!”

Old Andy Boyle got some sticks and some coal oil and, under the protection of rifles, started a fire against a street door of the house. Jack Long and two others also fired the house in the rear. A keg of powder had been concealed under the floor. The flames reached this powder, and there was an explosion that did more than anything else toward ending the siege.

Josiah Gordon “Doc” Scurlock (1850-1929)

At about dusk, Bob Beckwith, old man Pierce, and one other man ran around toward the rear of the house. Beckwith called out to the inmates to surrender. They demanded that the sheriff come for a parley. “I’m a deputy sheriff,” replied Beckwith. It was dark, or nearly so. Several figures burst out of the rear door of the burning house, among these the unfortunate McSween. Around and ahead of him ran Billy the Kid, Scurlock, French, O’Folliard, Bowdre, and others. The flashing of six shooters at close range ended the three-day battle. McSween, still unarmed, dropped dead. He was found half sitting, leaning against the corral wall. Bob Beckwith of the Peppin forces fell almost simultaneously, killed by Billy the Kid. Near McSween’s body lay Romero, Semora, and Harvey Norris. The latter was a young Kansan, newly arrived in that country, of whom little was known.

With the McSween party, there was one game Mexican, Ighenio Salazar, who is alive today by a miracle. Salazar was shot down in the rush from the house, being struck by two bullets. He feigned death. Old Andy Boyle stood over him with his gun cocked. “I guess he’s dead,” said Andy. “If I thought he wasn’t, I shoot him some more.” They then jumped on Salazar’s body to assure themselves. In the darkness, Salazar rolled over into a ditch, later made his escape, stopped his wounds with some corn husks, and found concealment in a Mexican house until he subsequently recovered.

This fight cost McSween his life just when he thought he had attained success. Four days before he was killed, he had word from the United States Government’s commissioner that the President had deposed Governor Axtell of New Mexico on account of his appointment of George Peppin as sheriff and on charges that Axtell was favoring the Murphy faction. General Lew Wallace was now sent out as Governor of New Mexico, invested with “extraordinary powers.” He needed them. President Hayes had issued a governmental proclamation calling upon these desperate fighting men to lay down their arms, but it was not certain they would easily be persuaded. It was a long way to Washington and a short way to a six-shooter.

General Wallace assured Mrs. McSween of protection, but he found there was no such thing as getting to the bottom of the Lincoln County War. It would have been necessary to hang the county’s entire population to execute a formal justice. Almost none of the indictments “stuck,” and the cases were dismissed one by one. The thing was too big for the law.

Billy the Kid was the only man ever actually indicted and brought to trial for a killing during the Lincoln County War. Many residents of Lincoln today declare that the Kid was made a scapegoat. Many a man even today charges Governor Wallace with bad faith. Governor Wallace met the Kid by appointment at the Ellis House in Lincoln. The Kid came in fully armed, and the old soldier was surprised to see a bright-faced and pleasant-talking boy in him. In the presence of two witnesses now living, Governor Wallace asked the Kid to come in and lay down his arms and promised to pardon him if he would stand his trial and if he should be convicted in the courts. The Kid declined. “There is no justice for me in the courts of this country now,” said he. “I’ve gone too far.” And so he returned with his little gang of outlaws to meet a dramatic end after further incidents in a singular and blood-stained career.

The Lincoln County War now spread wider than even the boundaries of the United States. A United States deputy, Wiederman, had been employed by the father of the murdered John Tunstall to take care of the Tunstall estates and to secure some kind of British revenge for his murder. Wiederman falsely persuaded Tunstall that he had helped kill Frank Baker and Billy Morton, and Tunstall made him rich; Wiederman went to England, where it was safer. The British legation took up the matter of Tunstall’s death, and the slow-moving governmental wheels at Washington began to revolve. A United States indemnity was paid for Tunstall’s life.

Mrs. McSween, meantime, kept up her work in the local courts. Sometime after her husband’s death, she employed a lawyer named Chapman of Las Vegas, a one-armed man, to undertake the dangerous task of aiding her in her work of revenge. By this time, most of the fighters were disposed to lay down their arms. The war had ruined the whole country’s society. Murphy & Co. had long ago mortgaged everything they had and a good many things they did not have, e.g., some of John Chisum’s cattle, to Tom Catron of Santa Fe. A big peace talk was made in the town, and it was agreed that, as there was no longer any advantage of a financial nature in keeping up the war, all parties concerned might as well quit organized fighting and engage in individual pillage instead. Murphy & Co. were ruined. Murphy and McSween were both dead. Chisum could be depended upon to pay some of the debts to the warriors through stolen cattle, if not through signed checks. Why should good, game men go on killing each other for nothing? This was the argument used.

At this conference, there were, on the Murphy side, Jesse Evans, James Dolan, and Bill Campbell. On the other side were Billy the Kid, Tom O’Folliard, and the game Mexican, Salazar. Each of these men had a .45 Colt at his belt and a cocked Winchester in his hand. At last, however, the six men shook hands. They agreed to end the war. Then, in frontier fashion, they set off for the nearest saloon.

The Las Vegas lawyer, Chapman, happened to cross the street as these desperate fighting men, used to killing, now well drunken, came out, all armed, and all swearing friendship.

“Halt, you, there!” cried Bill Campbell to Chapman, and the latter paused. “Damn you,” said Campbell to Chapman, “you are the — — of a — — that has come down here to stir up trouble among us fellows. We’re peaceful. It’s all settled, and we’re friends now. Now, damn you, just to show you’re peaceable too, you dance.”

“I’m a gentleman,” said Chapman, “and I’ll dance for no ruffian.” An instant later, shot through the heart by Campbell’s six-shooter, as is alleged, he lay dead in the roadway. No one dared disturb his body. He was shot at such close range that some papers in his coat pocket took fire from the powder flash, and his body was partially consumed as it lay there on the road.

James Dolan, Billy Matthews, and Bill Campbell were indicted and tried for this killing. Dolan and Matthews were acquitted. In default of a better jail, Campbell was kept in the guardhouse at Fort Stanton. One night, he disappeared in company with his guard and some United States cavalry horses. Since then, nothing has been heard of him. His real name was not Campbell but Ed Richardson.

Billy the Kid did not kill John Chisum, though all the country wondered at that fact. There was a story that he forced Chisum to sign a bill of sale for 800 head of cattle. He claimed that Chisum owed money to the McSween fighting men, to whom he had promised salaries that were never paid. Still, no evidence exists that Chisum ever made such a promise, although he sometimes sent a wagonload of supplies to the McSween fighting men.

John Chisum died of cancer at Eureka Springs, Missouri, on December 26, 1884, and his great holdings as a cattle king became somewhat involved afterward. He could once have sold out for $600,000 but later mortgaged his holdings for $250,000. He was concerned about a packing plant in Kansas City, a business into which others drew him and of which he knew nothing.

Major Murphy died at Santa Fe before the big fight at Lincoln. James Dolan died a few years later and lies buried in the little graveyard near the Fritz ranch. Riley, the other firm member, went to Colorado and was last heard of at Rocky Ford, where he was prosperous. The heritage of hatred was about all that McSween left to his widow, who presently married George L. Barber at Lincoln. It later proved herself to be a good businesswoman — good enough to make a fortune in the cattle business from the four hundred head of cattle John Chisum gave her to settle a debt he had owed McSween. She afterward established a fine ranch near Three Rivers, New Mexico.

George Peppin, known as the “Murphy sheriff” by the McSween faction, lived out his life on his little holding at the edge of Lincoln. He died in 1905. His rival, John Copeland, died in 1902. The street of Lincoln, one of the bloodiest of its size in the world, is silent. Another generation is growing up. William Brady, Major Brady’s eldest son, and Josephina Brady-Chavez, a daughter, live in Lincoln; and Bob Brady, another son of the murdered sheriff, was a long jailer at Lincoln jail. The law has arisen over the ruin wrought by lawlessness. Notably, although the law never punished the participants in this border conflict, the lawlessness was never ended by any vigilante movement. The fighting was so desperate and prolonged that it came to be held as warfare and not as murder. There is no doubt that barring the Kansas-Missouri Border War, this was the greatest of American border wars.

Go To the Next Chapter – The Stevens County War

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

About the Author: Excerpted from the book The Story of the Outlaw: A Study of the Western Desperado, by Emerson Hough; Outing Publishing Company, New York, 1907. This story is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clerical errors and updated for the modern reader. Emerson Hough (1857–1923).was an author and journalist who wrote factional accounts and historical novels of life in the American West. His works helped establish the Western as a popular genre in literature and motion pictures. For years, Hough wrote the feature “Out-of-Doors” for the Saturday Evening Post and contributed to other major magazines.

Also See:

Lincoln County War, New Mexico

Billy The Kid – Teenage Outlaw of the Southwest

Lawrence Murphy – Scoundrel Behind the Lincoln County War

Emerson Hough.

Other Works by Emerson Hough:

The Story of the Outlaw – A Study of the Western Desperado – Entire Text