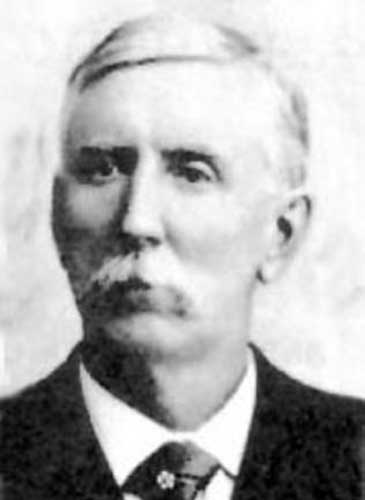

Joseph G. McCoy

Joseph G. McCoy was the founder of the cattle trade in Kansas, the originator of the Abilene Cattle Trail, and a cattle baron in his own right. McCoy was born in Sangamon County, Illinois, on December 21, 1837, the youngest of eleven children to David and Mary (Kirkpatrick) McCoy, natives of Virginia and Kentucky, respectively. He was educated in public schools and at Knox College. In 1861, he started in the cattle business and married Sarah Epler on October 22nd.

In 1867, he conceived the idea of establishing a shipping depot for cattle at some point in the West and knew that the railroad companies were interested in expanding their freight operations. He soon selected Abilene, Kansas, and opened the Abilene Trail through Indian Territory from Texas.

Some people sneered at his ideas, but he demonstrated their practicability. McCoy also built a hotel called the Drover’s Cottage, a stockyard, office, and bank in the little village along the Union Pacific Railroad that would serve as the shipping point.

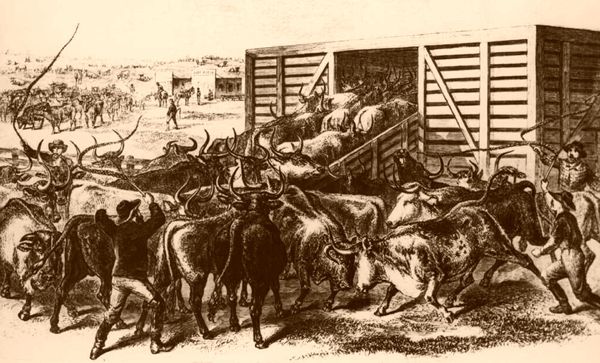

Driving Cattle

McCoy advertised extensively throughout Texas to encourage cattle owners to drive their cattle to market in Abilene. By 1868, about 75,000 cattle were shipped from Abilene. In 1870, thousands of Texas longhorn cattle, which were ideal for cattle trails due to their long legs and hard hoofs, were being driven to the shipping center at Abilene. By 1871, the number had increased to 600,000 or more, and as many as 5,000 cowboys were being paid off during a single day. Abilene soon became known as a rough town in the Old West.

McCoy lived in Abilene, where he was elected mayor in April 1871. Later that month, McCoy recommended and hired James B. “Wild Bill” Hickok to become Abilene’s marshal. It would seem that this was a good choice to tame the lawless town; however, Hickok spent most of his time in the Alamo Saloon, the center of the town’s wildlife, and was not too friendly with the “upstanding” folks of Abilene. Instead, he spent more time at the gaming tables and with the ladies of the evening than he did taking care of his sheriff duties.

By October 1871, the citizens of Abilene had enough of the rowdiness and lawlessness created by the cattle drives. The city fathers told the Texans there could be no more cattle drives through their town and dismissed Hickok as city marshal in December. It was the last big year for Abilene, as more than 40,000 head of cattle were shipped out by rail. New railheads were built to Newton, Wichita, and Ellsworth, becoming the favored shipping points. During its four-year reign, over three million head of cattle were driven up the Chisholm Trail and shipped from Abilene. With the cowboys gone, the town quieted down into a peaceful, law-abiding community.

In the meantime, McCoy’s personal fortune had been exhausted by constant promotion, a family to support, and the shifting winds of the volatile livestock market. His time as an Abilene Cattle Baron had come to an end. He spent some time traveling to some of the new cowtowns but by 1872 was living in Wichita, where he became a promotion agent for American and Texas Refrigerator Car and began to document his experiences in a book entitled Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest, which was published in 1874. In 1880, he was commissioned as a livestock dealer in Kansas City, Missouri, and was employed by the U.S. Census Bureau to report on the livestock industry for the eleventh census. Some years later, he was serving as an agent for the Cherokee Nation and living in Oklahoma. By 1890, he had returned to Kansas and ran unsuccessfully as a candidate for the U.S. Congress.

Joseph McCoy died in Kansas City, Missouri, on October 19, 1915. One story about the cattle baron alleges that McCoy bragged before leaving Chicago that he would bring 200,000 head in 10 years and actually brought two million head in four years, which led to the phrase “It’s the Real McCoy.” However, the origin of the phrase is probably from a Scottish poem published in 1856 that used “The real MacKay.” Other associations of the phrase are with inventor Elijah McCoy’s oil-drip cup, which was preferred by many railroad engineers over other “inferior” products.

Broadway Avenue, Abilene, Kansas 1875.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Abilene – Queen of the Kansas Cowtowns