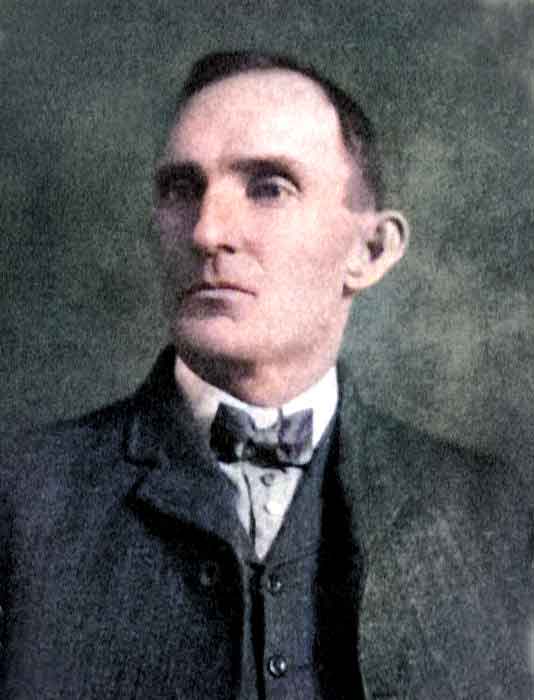

Jim Miller, touch of color LOA.

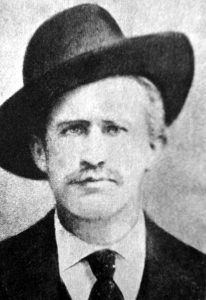

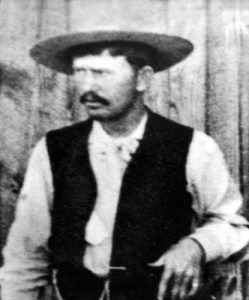

James “Jim” Brown Miller was one of the worst of the many violent men of the Old West. Miller was a law officer, Texas Ranger, outlaw, and professional killer who was said to have killed 12 people during gunfights and more in outlaw activities and assignations. He was often impeccably dressed with good manners; he didn’t smoke or drink and often attended church, earning him the nickname “Deacon Miller.” But, he was a wolf in sheep’s clothing and was seemingly one of those “bad seeds” from an early age.

On October 25, 1861 (some sources list October 24, 1866), Miller was born in Van Buren, Arkansas, to Jacob and Cynthia Basham Miller. When he was just a year old, he and his family moved to Texas in 1862. Jim’s father, Jacob, a stonemason, helped build the first capitol building in Austin. However, somewhere along the line, Jacob died as his mother was listed as a widow in census reports. When the boy was eight, some accounts said he killed his grandparents. However, this has never proven to be true.

By 1880, he was documented as living with his widowed mother and siblings in Coryell County. Four years later, his sister Georgia married John Coop, a man Jim Miller detested. On July 30, 1884, John Coop was killed by a shotgun blast while in bed at his home about eight miles northwest of Gatesville, Texas, in Coryell County. It was well known that Jim did not like his brother-in-law, and he was soon arrested for the murder. He was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. However, his attorneys took the case to the Texas Court of Appeals, where the conviction was reversed on a technicality.

Train Robbery

Afterward, Miller hooked up with an outlaw gang in San Saba County, Texas, robbing trains and stagecoaches and often killing in the process. He also purchased a one-half interest in a saloon in San Saba. At that time, he also embarked on a career as an assassin, casually proclaiming that he would murder anyone for money (accounts of his price vary between $150 and $2,000.) In his newfound career, he eventually earned a reputation for getting the job done quickly and efficiently, usually using a shotgun ambush at night.

In appearance, Miller was a mild-mannered man, never cursed, didn’t drink or smoke, and was very well dressed, wearing a white shirt with a stiff collar, a stick pin on his lapel, a diamond ring, and always wearing a heavy frock coat, regardless of how hot it might be. Despite his occupation, he was often known to attend church and read the bible. He was not a fast-draw gunfighter like many other men of the West but was quick to use a gun when it suited him. In addition to killing for hire, he was known to have killed several men in saloons when arguments erupted over poker games.

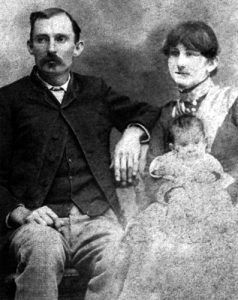

In about 1882, Miller was arrested and disarmed by young San Saba Deputy Sheriff Dee Harkey, later one of the most famous lawmen of the West. Shortly afterward, Miller drifted into McCulloch County, where he raced horses and worked as a cowboy for Emmanuel “Mannen” Clements, Sr., a violent man who was the older cousin of John Wesley Hardin. While there, Miller became good friends with Emmanuel’s son, Emmanuel “Mannie” Clements, Jr., and Mannen’s daughter, Sallie. Jim and Sallie married in McCulloch County on February 15, 1888, and would eventually have four children.

Miller next drifted through southeast New Mexico and West Texas along the Mexican border. Little is known of his activities during these years, but he would later brag: “lost my notch stick on Mexicans that I killed out on the border.”

By 1891, Miller was in Pecos, Texas, where Reeves County Sheriff George A. “Bud” Frazer soon hired him. The 27-year-old Frazer, who had been sheriff for less than a year, was badly in need of a deputy in the frontier town and asked few questions of Miller. In those days, asking too many questions about one’s past was considered rude. It would be a fatal mistake for Frazer.

Miller soon moved his family, along with brother-in-law Mannie Clements, to Pecos, where the family attended church and was an upstanding group by all appearances. At about the same time, cattle rustling and horse theft increased up and down the Pecos Valley, and Miller spent much of his time pursuing the thieves. But, when he never captured any, it raised suspicions in the mind of local gunfighter and hard-case Barney Riggs, who just happened to be Bud Frazer’s brother-in-law. As the increase in thefts had started to occur at about the same time as Miller became a deputy, Riggs pointed out that perhaps Miller should be considered a suspect and suggested that Miller be fired. When Frazer confronted his deputy, Miller laughed off the accusation.

Miller, supported by members of his church and with no proof of the allegations, was kept on by Frazer and continued to serve as a deputy. However, when Miller killed a Mexican prisoner who was “trying to escape,” Frazer investigated. Barney Riggs alleged that Miller had murdered the man because he knew where the deputy had hidden a pair of stolen mules. When Frazer found that Riggs was correct and located the stolen mules, he immediately fired Miller. This would be the beginning of the deadly Frazer-Miller feud, which would last for the next several years.

In the 1892 Pecos Sheriff’s election, Jim Miller opposed Bud Frazer but lost. However, this did not stop Miller from getting appointed as the Pecos City Marshal. Marshal Jim Miller then hired his brother-in-law, Mannie Clements, as his deputy. He surrounded himself with gunmen, including a hard-case gunfighter named Bill Earhart, John Denson, another cousin of John Wesley Hardin’s, and Martin Q. Hardin, who is not known to have been related to John Wesley, but the two referred to themselves as “cousins.”

In May 1893, Sheriff Frazer was away on business, and Miller’s criminal element virtually took over the town. In the meantime, Miller and his henchmen were also hatching a plan to assassinate him upon his return. When the sheriff returned, the plan was to stage a shoot-out on the railroad station platform. Nearby would be a third man who would shoot Frazer, making it appear like a stray bullet had killed him. However, when Con Gibson overheard the plan while in a local saloon, he contacted Frazer to let him know about it. Frazer, in turn, contacted the Texas Rangers, and when Frazer arrived, he was flanked by Texas Rangers. Captain John R. Hughes soon arrested Miller, Clements, and Martin Hardin. The three were indicted on September 7, 1893, for conspiring to kill Frazer. The case was transferred to El Paso to be tried; however, Con Gibson, the primary prosecution witness, fled to nearby Eddy (now Carlsbad,) New Mexico, where Miller’s henchman shot and killed John Denson. With their witness gone, the state was forced to release the three prisoners.

Though Miller had once more escaped the long arm of the law, he did lose his job as marshal and bought a hotel in Pecos. Miller then appeared to be living the life of an honest citizen, and the town settled down. However, word began to spread that Frazer couldn’t handle Miller and had no business being sheriff. The talk naturally built up resentment in the young sheriff.

On April 18, 1894, when Bud Frazer encountered Miller on the street, he yelled at him, “Jim, you’re a cattle rustler and murderer! Here’s one for Con Gibson.” Frazer then opened fire on Miller, striking him in the right arm near the shoulder. Miller fired back but succeeded in only grazing a man named Joe Kraus, a local storekeeper. Frazer then emptied his pistol into Miller’s chest, and he collapsed. Bud then walked away only to find out later that Miller wasn’t dead, amazingly.

Several of his friends picked up Miller and carried him into his hotel. Also surprised that the man wasn’t dead, they discovered a metal breastplate plate that Miller wore under his coat. Now, it became clear why the hired killer always wore a heavy frock coat. However, that information would not be shared with Frazer.

Though Miller survived, he would spend the next several months convalescing, and there were no more conflicts between the two men, though Miller had been making threats the entire time. In November 1894, when the sheriff election came up again, Frazer lost. He then moved to Carlsbad, New Mexico, where he opened a livery stable.

Frazer returned to Pecos the next month to settle his affairs. The ex-sheriff encountered Jim Miller in front of Zimmer’s blacksmith shop on December 26, 1894. Having heard the frequent threats Miller had made against him, Frazer drew his gun, sending two shots into Miller’s right arm and left leg. Jim began firing left-handed without success while Frazer sent two more slugs into Miller’s chest. Amazed again that Miller was still alive and standing, the confused Frazer fled. Only later would the Sheriff find out about Miller’s protective breastplate.

In March 1895, John Wesley Hardin, who had become an attorney while in prison, arrived in Pecos and filed charges of attempted murder against Bud Frazer. The ex-sheriff’s trial was scheduled to be heard in El Paso. However, Hardin was killed before it came to trial, and Frazer was acquitted in May 1896. Miller, of course, was furious and, in the end, would take his final revenge.

Bud Frazer was not Miller’s only target. Barney Riggs, Bud’s brother-in-law, hard-case gunfighter, and the man who had exposed Miller’s thievery while he was a deputy, was also in Jim’s crosshairs. Riggs is also said to have been the only man Killer Jim Miller ever truly feared. In typical fashion, Miller decided that Riggs should also die. In early 1896, two of Miller’s henchmen — John Denson and Bill Earhart, were overhead in Fort Stockton, Texas, muttering threats against Barney Riggs. Later, the pair left for Pecos, Texas, to seek out Miller’s nemesis. However, U.S. Deputy Marshal Dee Harkey wired a warning telegram to Riggs, and when the pair arrived, Barney avoided them. However, on the morning of March 3, he was alone as Riggs was substituting for a friend as a bartender in R.S. Johnson’s Saloon. Denson and Earhart burst into the room. A shot from Earhart grazed Barney, who instantly fired back, killing the other man. He then grappled with Denson before the would-be assassin was able to flee. Riggs followed, and as Denson was running down the street, Riggs shot him in the back of his head, killing him on the spot. Miller’s scheme to eliminate the one man he feared had failed. After the shooting, Riggs surrendered himself. He was later tried for murder and acquitted.

Later that year, even though Bud Frazer knew that Miller was out to get him, he made the mistake of visiting family in nearby Toyah, Texas, in September 1896. On the morning of the 14th, Bud played cards with friends in a saloon when Miller pushed open the door and fired with both barrels, practically blowing Frazer’s head from his body. When Bud’s distraught sister approached Miller with a gun, he said to her: “I’ll give you what your brother got — I’ll shoot you right in the face!”

Once again, the far too lucky and evil Jim Miller was acquitted of the murder of Frazer, his defense being that “he had done no worse than Frazer.” During the trial, a man named Joe Earp (no known relation to the Earp Brothers,) who had testified in his trial, became his next target. Several weeks afterward, Joe Earp was shot down, reportedly by Miller himself, before galloping 100 miles in one night to establish an alibi.

Next, Miller made his way to Memphis in the Texas Panhandle. There, he ran a saloon where he openly boasted of his many murders. He was also said to have worked as a part-time deputy sheriff again, and in August 1898, he was allegedly made a Texas Ranger for a brief period. Whether this is accurate is unknown. There was a thin line between law and crime then, but many accounts indicate he was only masquerading.

In 1899, an attorney named Stanley prosecuted Miller on a charge of subornation of perjury, meaning persuading another to commit perjury. This charge was allegedly related to Joe Earp’s account during Miller’s murder trial of Bud Frazer. Mysteriously, Attorney Stanley soon after died of food poisoning, which history tells was more than likely another of Miller’s work.

Miller then returned to the Pecos area, where he spent some time in Monahans. However, by 1900, he and his wife, Sallie, lived in Fort Worth, where the assassin became involved in real estate and did very well financially. Even so, killing appeared to be in his blood, and his financial situation had little impact on his choice to continue his career as a killer. At that time, the great sheep wars were taking place with the cattlemen, and Miller was quick to hire out to kill the sheepmen at just $150 per job, killing as many as a dozen men. At the same time, numerous feuds were going on regarding fences, which got in the way of the great cattle herds, and Miller was more than happy to help the cattlemen by killing the farmers who fenced their land.

In 1904, Miller ambushed and killed Lubbock lawyer James Jarrott, who had successfully represented several farmers against the big cattle interests. He received $500 for ambushing the attorney. That same year, he also killed a man he did real estate business within Fort Worth. T.D. “Frank” Fore was an honest businessman who threatened to tell a grand jury that Miller was selling lots submerged in the Gulf of Mexico. On March 10, 1904, Miller cornered Fore in the washroom of the Delaware Hotel and shot him to death. As people rushed to see what had happened, Miller fell over Fore’s body, tears in his eyes, exclaiming, “I did everything I could to keep him from reaching for his gun.” Amazingly, Miller was acquitted again.

Jim Miller, touch of color LOA

Continuing his wicked ways, Miller took a job in Indian Territory in 1906 in the small town of Orr, Oklahoma, in the Chickasaw Nation. There lived a U.S. Deputy Marshal, Ben Collins, who also served as an Indian policeman.

Several years earlier, Ben Collins had tried to arrest a man named Port Pruitt, a prominent citizen in Emet, Oklahoma. Resisting arrest, Collins shot him, leaving Pruitt partially paralyzed. Port and his brother publicly swore vengeance on Ben Collins. They soon hired Killer Miller for $1,800 to care for their enemy. On August 1, 1906, as Collins was riding home to his farm, he received a load of buckshot, which knocked him from his horse. However, the young lawman got off four rounds while on the ground; another shotgun blast soon tore through his face. An intense investigation soon began, pointing at Killer Miller and another man named Washmood.

Once again arrested, Miller spent a short time in jail but was soon released on bail. Before Miller could be tried, any witnesses were soon killed, and once again, the prosecution died from a lack of witnesses and evidence.

Next, Miller was accused of killing Pat Garrett on February 28, 1908. Garrett was allegedly killed because of a land dispute, and by some accounts, Miller murdered a paid assassin. However, this is unlikely, as Wayne Brazel confessed to the crime later. Carl Adamson, who was married to a cousin of Sallie Miller, was also with Garrett when he was killed. This led to the rumors that Miller was involved. However, most historians agree that Garrett’s murder happened without the killer’s involvement.

Gus Bobbitt

On December 29, 1908, Emmanuel “Mannie” Clements, Jr., Miller’s longtime friend and cohort, was killed in a saloon fight in El Paso, Texas. Miller swore revenge and, no doubt, would have followed through, except he had been offered $1,700 to kill former U.S. Marshal Allen Augustus “Gus” Bobbitt in Ada, Oklahoma.

At this time, the flourishing town of Ada was a thriving cotton center but also had a violent reputation. In 1908, some 36 people were murdered. Bobbitt had retired from his U.S. Deputy Marshal position after Oklahoma became a state the previous year and moved to a ranch near Roff, Oklahoma. However, though retired, Bobbitt was not quiet about his feelings about many of the events in the area. Several citizens, including saloon owners Jesse West and Joe Allen, were practicing what was known as “Indian Skinning.” This practice involved taking advantage of Native Americans, who had been granted 160 acres each in exchange for their reservation land. Though Oklahoma law required that any such land being sold to whites had to have the approval of the county court judge, several opportunists took advantage of the situation, often getting the Indians drunk and buying their 160 acres for as low as $50.

From left to right: Jim Miller, Joe Allen, Berry Burrell, and Jesse West hanged

by vigilantes in Ada, Oklahoma, 1909.

Appalled at what was happening, Gus Bobbitt began publicizing the events and pushed for changes to elected offices in the town and county. As a result, those who were handsomely profiting hired the notorious Jim Miller to solve the problem. On February 27, 1909, Bobbitt was shot as he drove his wagon home from Ada. He lived for about an hour, but before he died, he instructed his wife on how to dispose of his property, which included $1,000 as a reward for the man who had killed him.

Within no time, a posse was after Bobbitt’s killer and others, hoping to land the reward. Having long escaped “Scot Free,” as he had many times before, Miller was confident that his escape was sloppy this time. The posse soon found his horse at the home of a man named Williamson, who was said to have been yet another one of Miller’s many relatives. Miller borrowed a mare from Williamson, admitting that he had killed a man and threatened to kill Williamson if he talked.

In the end, the posse tracked down the notorious killer and found that Bobbit’s paid assassin was, indeed, Jim Miller, the result of a conspiracy among several individuals. A livestock speculator named Berry Burrell had hired Miller, but he was not alone. Several others involved in the profitable “Indian Skinning” were also part of the murder.

In April, Miller, along with Jesse West, Joe Allen, and Berry B. Burrell, were arrested for the killing of Gus Bobbitt. By April 6, 1909, all the conspirators had been jailed in Ada, Oklahoma. Though it was well-known that Miller and the others had killed Bobbitt in a murder-for-hire scheme, the evidence was not solid. Awareness of the lack of evidence and Miller’s history of never having suffered the consequences of his actions caused a lynch mob of about 50 men to storm the jail on April 19. The mob quickly overpowered the jailers and dragged the four men outside. In an abandoned livery stable behind the jail, the prisoners were bound with baling wire and ropes tossed over the rafters. Miller’s cohorts were hanged first, after which the vigilantes asked him to admit his crimes. Miller then allegedly responded: “Let the record show that I’ve killed 51 men.” Before he died, he also asked for his black broadcloth coat to be draped around his shoulders. He then said, “Let her rip!”

After his death, one respected citizen said of Miller: “He was just a killer — the worst man I ever knew.”

Miller’s body was returned to Texas, where he is buried in the Oakwood Cemetery in Fort Worth.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Also See: