Under the orders of the War Department, Lieutenant Zebulon Montgomery Pike, with a force consisting of two lieutenants, a surgeon, a sergeant, two corporals, 16 privates, and an interpreter, set out in two boats from Belle Fontaine, near St. Louis, Missouri, on July 15, 1806, to ” explore the internal parts of Louisiana.”

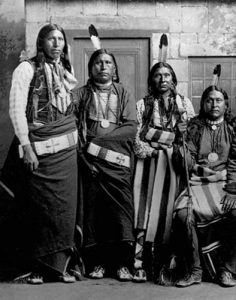

Accompanying him were chiefs and headmen of the Osage and Pawnee Indians, through which nations the expedition was intended to pass. He also took several women and children returning to their nations from captivity among the Pottawatomi, having been freed by the United States government. La Charette was reached on July 21, where Pike found Lieutenant James B. Wilkinson, Dr. John H. Robinson, and another interpreter, all of whom had gone on before, waiting for him.

On September 6, the company arrived near the present town of Harding, Kansas, and passed over the divide separating the Osage from the Neosho Valley. On September 10, he reached the divide between the Neosho and Verdigris Rivers and, on the 11th, camped on the latter stream, not far from the town of Bazaar, in Chase County, Kansas.

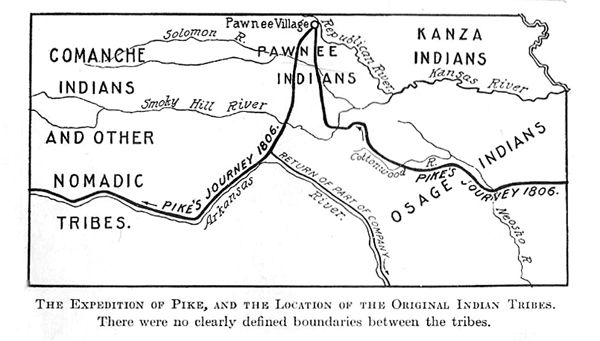

The beautiful prairies, covered with wildflowers and abounding with game, kindled the warmest praises of Pike. On September 12, he wrote that he saw at one view on the flowered plain below buffalo, elk, deer, antelope, and panther from the top of a hill. This was the hunting ground of the Kanza or Kaw Indians, and the animals began to appear almost without numbers. On the 14th, the expedition journeyed through an unending herd of buffalo all day long, which merely opened ranks to let the intruders pass and then closed again as if nothing had happened. On the 15th, a large unoccupied encampment of the Kanza Indians was passed, and Pike observed the buffalo running in the distance, indicating either Indians or white men. On this day, he camped near Tampa in Marion County. Two days later, he reached the Smoky Hill River, and after this, the game began to grow scarcer. He continued his journey to the mouth of the Saline River, which was reached on September 18, and from that point turned almost directly north, and on the 25th, reached the Pawnee village, near where the town of Scandia now stands, in Republic County. Pike was now on the Republican branch of the Kansas River, having crossed the Great Saline, the Little Saline, and Solomon’s Fork.

Sometime before Pike left St. Louis, Missouri, news of his projected expedition was carried to the governor of New Spain (Mexico), and a party of over 300 Spanish troops under Lieutenant Malgares was sent out to intercept him. Between the mouth of the Saline and the Republican Rivers, Pike crossed the trail of this party but was fortunate not to come in contact with the Spaniards at that time. Malgares had been to the Pawnee village before Pike arrived there and had endeavored to poison the minds of the Indians against the Americans. He had partially succeeded, too, for when Pike held a grand council with the tribe on September 29, he noticed that the Pawnee chiefs showed a tendency to look with disdain upon his little force of 20 white soldiers, which certainly made a much less imposing appearance than the large Spanish force of Malgares. Of this council, Pike gives the following explicit account in his journal of the expedition:

“The notes I took at the grand council held with the Pawnee Nation were seized by the Spanish government, and all my speeches to the different nations. But it may be interesting to observe here, in case they should never be returned, that the Spaniards had left several of their flags in this village, one of which was unfurled at the chief’s door the day of the grand council and among various demands and charges I gave them was, that the said flag should be delivered to me. One of the United States flags be received and hoisted in its place. This probably was carrying the pride of nations a little too far, as there had so lately been a large force of Spanish Cavalry at the village, which had made a great impression on the minds of the young men as to their power, consequence, etc., which my appearance with 20 infantry was by no means calculated to remove. After the chiefs had replied to various parts of my discourse but were silent as to the flag, I again reiterated the demand for the flag, adding that it was impossible for the nation to have two fathers, that they must either be children of the Spaniards or acknowledge their American father.’

After a silence of some time, an old man rose, went to the door, took down the Spanish flag, brought it and laid it at my feet, and then received the American flag and elevated it on the staff which had lately borne the standard of his Catholic Majesty. This gave great satisfaction to the Osage and Kaw, who decidedly avow themselves to be under American protection. Perceiving that every face in the council was clouded with sorrow as if some great national calamity was about to befall them, I took up the contested colors and told them ‘that as they had now shown themselves dutiful children in acknowledging their great American father, I did not wish to embarrass them with the Spaniards, for it was the wish of the Americans that their red brethren should remain peaceably round their own fires, and not embroil themselves in any dispute between the white people; and that for fear the Spaniards might return there in force again, I returned them their flag, but with the injunction that it should never be hoisted again during our stay.’ At this, there was a general shout of applause, and the charge was particularly attended to.”

Thus, the United States flag was raised for the first time in the State of Kansas on September 29, 1806.

Pike obtained horses from the Indians and left the Pawnee village on October 7, taking a course a little west of south. On the 8th, he came again upon the Spanish trail and, at one of the camps, counted 59 fires, which, at six men to a fire, signified a force of 354 troopers. Solomon’s Fork was again crossed on the 9th, much farther to the west, and another Spanish camp was found here. The party reached the Smoky Hill Fork on the 13th, not far from the boundary line of the counties of Russell and Ellsworth, and the following day, arrived at the divide between the Arkansas and the Kansas Rivers. Here, Pike and a small party became lost on the prairie and did not turn up for several days. The expedition continued to the Arkansas River, where the lost party under Pike overtook it. The river was crossed on the 19th.

Here, the expedition was divided, with part returning down the Arkansas River and the other portion going up to the mountains to discover the headwaters of the Red River and descend that unknown stream- unknown to the Americans. Canoes were made of buffalo, and deer hides stretched over wooden frames, filled with provisions, arms, and ammunition. In these boats, Lieutenant Wilkinson, six soldiers, and two Osage Indians embarked for Fort Adams on the Mississippi River below Natchez, Mississippi. On January 8, 1807, they reached Arkansas Post, near the mouth of the Arkansas River, after severe hardships and passing through many dangers from hostile Indians. Pike advanced rapidly up the Arkansas River and, on October 31st, saw much crystalline salt on the ground’s surface. At that time, he was not far from the present town of Kinsley in Edwards County, Kansas.

By November 9, he was near where Hartland in Kearny County, Kansas, once stood. Here, at one of the Spanish encampments, he counted 96 fires, indicating that the force had been augmented from 600 to 700 troopers.

A few days later, he crossed into what is now the State of Colorado and, on the 15th, reached Purgatory River, a branch of the Arkansas River. His purpose was to meet with the Comanche Indians near the Arkansas River headwaters, then strike across the country to the head of Red River and descend to Natchitoches according to the original plan.

Thus far, Pike had ascertained the sources of the Little Osage and the Neosho Rivers, had passed around the head of the Kansas River, and had discovered the headwaters of the South Platte River. He was now intent on finding the upper sources of the Red River. What Pike called the third fork was reached on November 23rd. He wrote: “As the river appeared to be dividing itself into many small branches and, of course, must be near its extreme source, I concluded to put the party in a defensible situation; and then ascend the north fork to the high point of the blue mountain, which we conceived would be one day’s march, to be enabled from its pinnacle to lay down the various branches and positions of the country.”

The “third fork” was the St. Charles River, and Pike’s encampment was made at what he called the “grand forks,” or at the junction of the Fountain River with the Arkansas River. The high point he referred to would later be named Pike’s Peak. His men cut the necessary logs the next day and erected a strong breastwork, five feet high on three sides, with the other opening on the south bank of the Arkansas River. Pike, Robinson, Miller, and Brown started for the mountains, leaving all the others at this fort. By the 26th, they had ascended so high that they looked down on the clouds rolling across the plain to the east. The next day, they reached the summit after a very difficult time, having been obliged often to wade in snow waist-deep. Returning, they reached the fort on the 29th, after which the surrounding country was explored for several miles in every direction in a vain search for the source of the Red River.

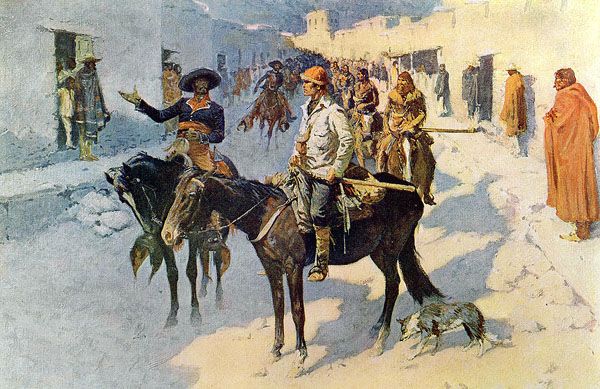

While Pike was in camp on the Rio del Norte River in New Mexico, he and his party were captured by a detachment of Spanish cavalry and conducted to Santa Fe in February 1807. He was well treated, and after being taken to Chihuahua, where his papers were confiscated, he was conducted east through Texas and finally liberated near Natchitoches, Louisiana.

Thus, the project of exploring the Red River was defeated, and one of the expedition’s objectives was not accomplished. The Spanish governor suspected that Pike was leagued with Aaron Burr to detach a portion of Spanish territory. But not a scrap was found to connect him with the “Burr Conspiracy.” The Spanish treated Pike and his men as respectable Americans advanced him $1,000 on the credit of the United States and escorted him to Natchitoches, which town was conceded to be within the American domain. Spain claimed the upper course of the Red River, and to have permitted Pike to explore it would have been tantamount to a recognition that American territory extended to that river. Three years later, Pike’s journal was published, and the wonderful possibilities of Kansas were thus made known to the English-speaking nations.

About the Article: Most of this historic text was published in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. However, the text on this page is not verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing have occurred.

Also See:

Discovery and Exploration of America