The region that now encompasses the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest of northeast Arizona was first inhabited by the Paleo People from 13,500 to 8000 B.C.

“Paleo” means ancient. Evidence suggests that groups of hunter-gatherers migrated across the Bering land-and-ice bridge between Siberia and Alaska when the sea level was several hundred feet lower than it is today. After reaching North America, the Paleo-Indians continued making their way south from Alaska either along the Pacific coast or along an ice-free area east of the Rocky Mountains.

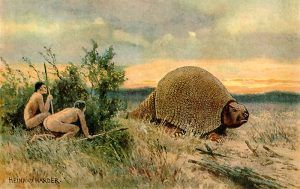

By the end of the last Ice Age, hunter-gatherers roamed the Southwest. During this time, the region was cooler with a grassland environment. People gathered wild plants for food and hunted extinct forms of bison and other large herd animals. The nomads used a device called an atlatl to throw their spears and darts. With their distinctive, elegant fluting, the projectile points of these ancient people helped define the Clovis and Folsom Cultures. Folsom and Clovis camps have been found within Petrified Forest National Park, as well as fluted projectile points made of petrified wood.

In about 500 B.C., the region was inhabited by what archeologists call the Basketmaker era. These people were more sedentary, living in stone-lined pit houses. As the Basketmaker period progressed, settlements moved from the mesa and dune tops to the slopes closer to farmland. They grew corn, squash, and, eventually, beans. They made beautiful baskets and Adamana Brown pottery. Their tool kit changed and broadened. The bow and arrow were introduced about A.D. 500. Petroglyphs throughout the area were created by these people, including images of humans and animals. By about 650 A.D., use of above-ground architecture began to evolve from storage to habitation. It appeared to have been a stressful period, with a major drought from 850 to 900 A.D.Following the Paleo, People were the natives of the Archaic Culture who lived in the region from about 8000 to 500 B.C. By 4000 B.C., the climate had become similar to that of today — it was warmer, and the monsoon pattern of precipitation had evolved. Because many of the large animals of the past were extinct, the people had to broaden their food source, including many different species of plants and animals. At this time, the people transitioned from a nomadic lifestyle to a sedentary agricultural society.

In about 950 A.D., the region was inhabited by what are referred to as the Ancestral Pueblo People, or Anasazi. While most of this period was similar in climate to the present, there was a prolonged widespread drought from 1271 to 1296 A.D. Although a few people still lived in pit houses, above-ground rooms were becoming prominent. Subterranean ceremonial rooms called kivas were introduced, and sites expanded across the landscape. Homes evolved into above-ground pueblos, some with multiple stories. People began to make corrugated, Black-on-Red, and polychrome pottery. Tools included manos and slab metates, petrified wood and obsidian points and scrapers, and locally made pottery. Artifacts link park sites to Wupatki near Flagstaff, the Hopi Mesas near Gallup, New Mexico, the Zuni, and the White Mountains sites. Many petroglyphs were made throughout the Little Colorado River Valley, including solar markers.

After the drought, which extended into the early 14th Century, there was a period of environmental change, the return of long winters and shorter growing seasons. These conditions extended well into the 19th Century. By 1300, A.D.m archeologists believe that the idea of Kachinas became widespread, marked by images of Kachinas in petroglyphs, pictographs, and kiva murals. Polychrome pottery became more elaborate, and Glaze-on-Red was added. Piki stones (for making piki bread) became evident. Their tool kit included small triangular projectile points. The population began to aggregate into larger communities, with over a hundred rooms, kivas, and frequently a plaza located along major drainages or near springs. By the end of the era, most of the Petrified Forest area appears to have been depopulated, but people still used the region for a travel corridor and resources. The Anasazi period lasted until about 1450.

By the time that European explorers came to the area, these ancient villages had been abandoned. Spanish conquistadors who arrived in the area in the 16th century allegedly named it El Desierto Pintado, meaning “Painted Desert. “These first Spanish explorers did not settle the area; however, they were focused on finding routes between their colonies along the Rio Grande and the Pacific Coast. Within the Petrified Forest National Park, Spanish inscriptions have been discovered from the late 1800s, descendants of some of the earliest non-American Indian settlers in the region.

Routes continued to be explored after the Southwest became part of U.S. territories in the mid-1800s. U.S. Army Lieutenant Amiel Whipple, surveying for a route along the 35th Parallel in 1853, passed down a broad sandy wash in the red badlands of the Painted Desert. Impressed with the deposits of petrified wood visible along the banks, Whipple named it Lithodendron (“stone tree”) Creek, the large wash that bisects the Wilderness Area of the park today. The Whipple Expedition was the source of the first published account of the petrified wood in what would become Petrified Forest National Park.

After Whipple’s expedition, an experienced explorer, E. F. Beale, was hired by the U.S. Government as a civilian contractor to build a wagon road along the 35th Parallel. Between 1857 and 1860, Beale made several trips from his ranch at Fort Tejon, California, building and improving the road. On his first journey, Beale was in charge of a government experiment in desert transport that included camels and their drivers. While Beale became convinced of the camels’ value, the government declared the experiment a failure. The wagon road lives on, still visible in spots across the Southwest, part of which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the late 1800s, settlers and private stage companies followed this ancient corridor. Homesteaders developed ranches that took advantage of the rich grasslands that would forever after bear the mark of grazing. In 1884, the Holbrook Times noted: The whole northern portion of the territory seems to be undergoing a great change… Our plains are stocked with thousands of cattle, horses and sheep… Cattle would graze in the Petrified Forest until the mid-20th century, and ranches are still some of the park’s best neighbors.

In 1904 and 1905, conservationist John Muir explored the Petrified Forest, and the following year, on December 8, 1906, the Petrified Forest National Monument was created by President Theodore Roosevelt.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Petrified Forest National Park

Sources:

National Park Service

North Dakota Studies

Paleo Indian Period of America