Established in 1610, Santa Fe, New Mexico, is the third oldest city founded by European colonists in the United States. Only St. Augustine, Florida, founded in 1565, and Jamestown, Virginia, are older. It is also the oldest capital city in the U.S., serving under five different governments; Spain, Tewa Puebloans, Mexico, the Confederate States of America, and the United States. Built upon the ruins of an abandoned Tanoan Indian village, Santa Fe was the capital of the “Kingdom of New Mexico,” which was claimed for Spain by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado in 1540. Its first governor, Don Pedro de Peralta, gave the city its full name, “La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís,” or “The Royal City of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi.”

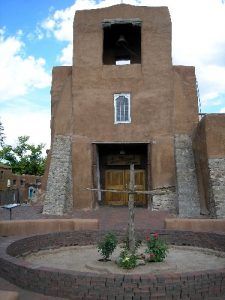

San Miguel Chapel in Santa Fe is the oldest church in the continental United States, constructed around 1610. The Palace of the Governors was built between 1610 and 1612 and is the oldest government building in the country.

During the next 70 years, the Spanish colonists and missionaries sought to subjugate and convert some 100,000 Pueblo Indians in the region. However, in 1680, the Pueblo Indians revolted, killing almost 400 Spanish colonists and driving the rest back into Mexico. The conquering Indians then burned most of the buildings in Santa Fe except for the Palace of the Governors and the San Miguel Chapel.

The Pueblo Indians occupied Santa Fe until 1693 when Don Diego de Vargas reestablished Spanish control. At this time, Santa Fe grew and prospered as a city but was interrupted by frequent Indian attacks by the Comanche, Apache, and Navajo tribes. As a result, Santa Fe citizens allied with the Pueblo Indians, which brought a more peaceful settlement. However, the Spanish policy of a closed empire heavily influenced many people’s lives in Santa Fe during these years because trade was restricted to Americans, British, and French.

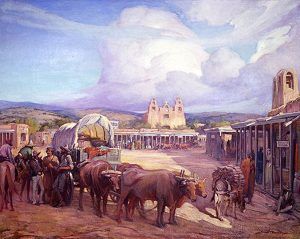

Santa Fe remained Spain’s provincial seat until 1821 when Mexico won its independence from Spain, and Santa Fe became the capital of the Mexican territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo, México. The Spanish policy of a closed empire ended at this time, and American trappers and traders moved into the region. William Becknell soon opened the l,000-mile-long Santa Fe Trail, leaving from Franklin, Missouri, with 21 men and a packed train of goods. Before long, Santa Fe would become the primary destination of hundreds of travelers seeking to trade with the city or move further west.

In 1837, northern New Mexico farmers rebelled against Mexican rule, killed the provincial governor in what has been called the Chimayó Rebellion (named after a village north of Santa Fe), and occupied the Santa Fe. However, the insurrectionists were soon defeated.

On August 18, 1846, during the early period of the Mexican-American War, an American army general, Stephen Watts Kearny, took Santa Fe and raised the American flag over the Plaza. There, he built Fort Marcy to prevent an uprising by Santa Fe citizens, though it was never needed.

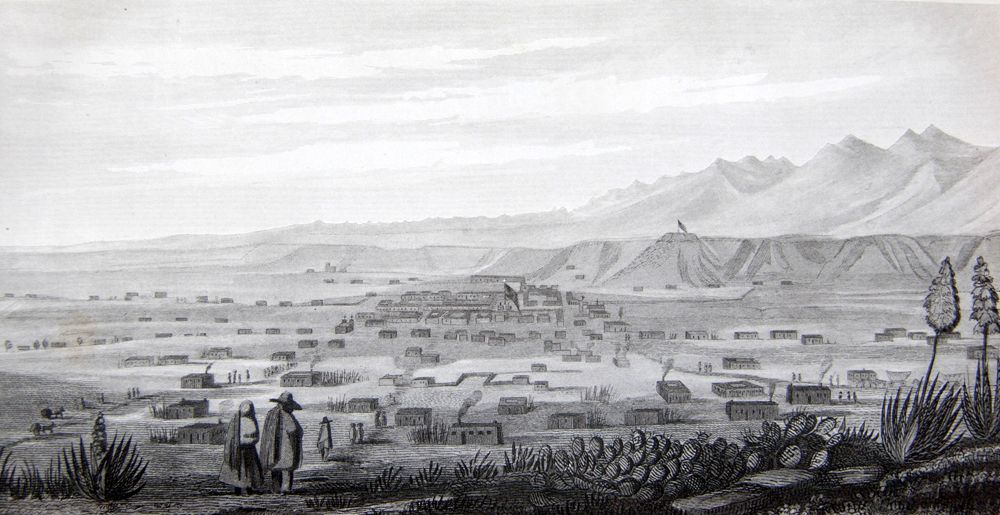

Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1846 by James Albert, a member of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. The American flag may be seen on the heights overlooking the town at Fort Marcy.

Two years later, in 1848, Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ceding New Mexico and California to the United States.

As part of the Confederate New Mexico Campaign of the Civil War, Brigadier General Henry Sibley occupied the city, flying the Confederate flag over Santa Fe for 27 days in March and April of 1862. Sibley was forced to withdraw after Union troops destroyed his logistical trains following the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

With the arrival of the telegraph in 1868 and the coming of the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe Railroad in 1880, Santa Fe and New Mexico Territory underwent an economic revolution. Corruption in government, however, accompanied the growth, and President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Lew Wallace as a territorial governor to “clean up New Mexico.” Wallace did such a good job that Billy the Kid threatened to come up to Santa Fe and kill him.

New Mexico gained statehood in 1912, with Santa Fe remaining the capital city. At that time, Santa Fe’s population was approximately 5,000 people.

Route 66 originally went through Santa Fe during its early years. Following the Old Pecos Trail from Santa Rosa, the path wound through Dilia, Romeroville, and Pecos to Santa Fe. Beyond the capital, Route 66 continued on a particularly nasty stretch down La Bajada Hill toward Albuquerque. One of the most challenging sections of the old road, the 500-foot drop along narrow switchbacks, struck terror in the hearts of many early travelers, so much so that locals were often hired to drive vehicles down the steep slope. Due to the political maneuverings of the New Mexico Governor in 1937, Route 66 was rerouted, bypassing Santa Fe and the Pecos River Valley. Having lost his re-election, Governor Hannett blamed the Santa Fe politicians for losing and vowing to get even; he rerouted the highway in his last few months as governor. So hastily was the road built that it barreled through public and private lands without the benefit of official right-of-ways.

By the time the new governor was in place, a new highway had connected Route 66 from Santa Rosa to Albuquerque, bypassing the capital city and many businesses. The new route was more direct and reduced some treacherous road conditions. It was along this path that I-40 would be built many years later.

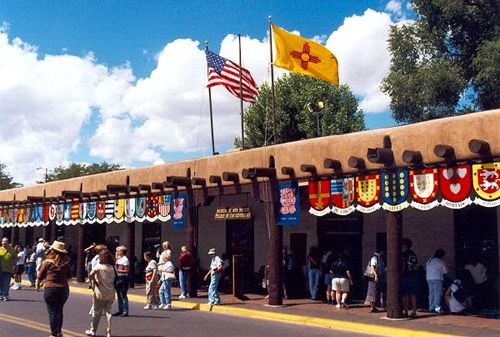

For many years this picturesque city has consciously attempted to preserve and display a regional architectural style. By a law passed in 1958, new and rebuilt buildings, especially those in designated historic districts, must exhibit a Spanish Territorial or Pueblo style of architecture, with flat roofs and other features suggestive of the area’s traditional adobe construction.

In addition to serving as the state capital, the city depends economically on art, tourism, construction, and real estate development. Set at the base of the Sangre de Cristo mountains, the city’s climate and cultural attractions have drawn an influx of new residents with above-average income and educational levels. Restaurants, boutiques, and galleries line the streets of the city center and Canyon Road.

The growth boom flagged temporarily in the mid-1990s when Debbie Jaramillo, who opposed tourism, was elected mayor. She was voted out after serving one term. The city continues to face the challenges of continuing drought conditions and a widening divide between locals and recent arrivals. Still, art and tourism remain Santa Fe’s biggest industries.

Nestled at 7,000 feet in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, Santa Fe boasts a population of almost 84,000 people. While in Santa Fe, visit the La Fonda Hotel, which has been providing a restful place for weary travelers since 1920. In 1926 the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad acquired the hotel, which they leased to Fred Harvey. From 1926 through 1969, the La Fonda was one of the famous Harvey Houses. Reportedly the La Fonda also hosts a resident ghost.

This 800-year-old Adobe house in Santa Fe, New Mexico, is claimed to be the oldest house in the United States.

Visitors also can see the historic Palace of the Governors, and the San Miguel Mission Church, visit Santa Fe’s many museums and stroll through numerous galleries and boutiques while visiting beautiful Santa Fe, New Mexico.

One other interesting note is that Santa Fe is reportedly extremely haunted. It is one of the few cities that offers a full schedule of “ghost tours” and “ghost walks” year-round, with as many as five operators conducting tours from Santa Fe’s historic plaza. These tours primarily focus on the ten-block historic area of Santa Fe, featuring such places as the La Posada and La Fonda Hotels, the Grant Corner Inn, the Palace of Governors, the oldest house in the nation, and other historic buildings. Some tours also include area superstitions and Santa Fe’s history of vigilantes, gunfights, murders, and hangings.

The treacherous road along the La Bajada Hill, located about ten miles southwest of Santa Fe, was once utilized by the Spanish moving along the El Camino Real and later became part of the pre-1937 path of Route 66. In 2017, Cochiti Pueblo blocked access to La Bajada Hill to prevent further abuse from visitors. Barbed wire fences now block roads at both the top and the bottom of the hill, and violators are accessed hefty fines.

Today’s Route 66 travelers should take Cerrillos Road (NM 14) as it leaves downtown Santa Fe making its way to the southwest for 7.5 miles before joining up with I-25. Continue on the Interstate for 18 miles and use exit #258, and travel about six miles to San Domingo Pueblo.

A great side trip presents itself along this route. Just 6.3 miles to the south of the junction of NM 14 and I-25 is El Rancho de los Golondrinas, just north of the village of La Cienega. This living history museum is a recreated Spanish Colonial village on over 200 acres. Take Exit #276 to the west frontage road, and turn right onto Los Pinos Road to the museum.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See: