“This is where we were born and raised… It is our native country. It is impossible for us to leave.”

– Ollokot (Frog)

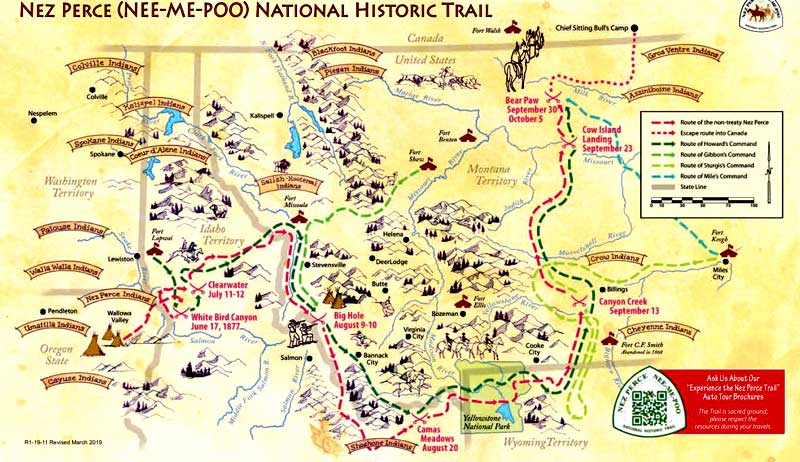

The Nez Perce National Historic Trail follows the route taken by a large band of the Nez Perce Indian tribe in 1877 when they attempted to flee from the U.S. Cavalry and get to Canada to avoid being forced onto a reservation. The 1,170-mile trail goes through Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, commemorating the significant sites and events during their 126-day journey.

The Nez Perce (Nimíipuu or Nee-Me-Poo) Trail was created in 1986 as part of the National Trails System Act and is managed by the U.S. Forest Service. It stretches from Wallowa Lake, Oregon, to the Bear Paw Battlefield near Chinook, Montana. It connects 38 sites across these four states that are part of the National Park Service’s Nez Perce National Historical Park.

Nez Perce National Historic Trail.

Since aiding the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1805, white explorers and settlers knew the Nez Perce Indians as friends. The Nez Perce lived in bands, welcoming traders and missionaries to a land framed by rivers, mountains, prairies, and valleys of present-day southeastern Washington, northeastern Oregon, and north-central Idaho. They moved throughout the region, including parts of what are now Montana and Wyoming, to fish, hunt, and trade.

After Great Britain and the United States settled a long-running disagreement over settlement and control of what was known then as Oregon country in 1846, American settlers began moving westward on the Oregon Trail in great numbers. The creation of the Oregon Territory in 1848 and Washington in 1853 triggered the treaty process.

Fifty years after the Lewis and Clark came through, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Ingalls Stevens met in council with Nez Perce leaders, which resulted in the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla with the U.S. Government. In this treaty, the Nez Perce agreed to cede 7.5 million acres of tribal land while retaining the right to hunt and fish in their “usual and accustomed places,” including some 5,000 square miles in Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. This area was set aside as the Nez Perce reservation, guaranteeing the tribe’s rights to their ancestral homeland in perpetuity. The Treaty of 1855 was ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1859.

However, in 1860, encroaching prospectors struck gold in Idaho, and within no time, thousands of miners, merchants, and settlers overran Nez Perce’s land, seized resources, and committed depredations against tribal members. In 1863, the federal government responded with new treaty talks, wanting to renegotiate the treaty and shrink the reservation to approximately one-tenth its original size, which included their treasured Wallowa region of northeastern Oregon and the Payette Lake region.

Many chiefs refused and angrily departed. Amid uncertainty, pressure, and promises, the remaining chiefs reluctantly agreed to a reservation 90 percent smaller than the 1855 treaty. Without authority, they ceded the lands of the Nez Perce, who left the council, in a document called “the Thief Treaty.” The white negotiators and the federal government distinguished those who signed as “treaty” Nez Perce; those who had not were the “non-treaty.” The 1863 Treaty was ratified by Congress in 1867.

For some years, non-treaty Nez Perce lived in the Wallowas and other locations within their traditional homelands. However, conflict with newcomers increased, particularly in the Wallowa region, the home of Chief Joseph and his band. Settlers petitioned the government to relocate the Nez Perce to the reduced 1863 Treaty reservation in Idaho, and in 1877, the U.S. Army was commanded to do so.

In May 1877, General Oliver Otis Howard and the nontreaty Nez Perce chiefs held a council at Fort Lapwai in Lapwai, Idaho. Howard summarily ordered them to bring their families and livestock to Lapwai in 30 days – or the army would make them comply by force. The chiefs argued the time was inadequate to gather the people and their livestock and asked for an extension, which Howard brusquely refused. Years of high-handedness, mistreatment, and the prospect of losing their homelands provoked several young warriors to vengeance. Riding from camp at Tolo Lake, Idaho, they avenged past murders of relatives by killing some white settlers.

Forced to abandon hopes for a peaceful move to the Lapwai Reservation, the Nez Perce chiefs saw a flight to Canada as their last promise for peace. The flight of the Nez Perce began on June 15, 1877. Led by Chiefs Joseph, Looking Glass, White Bird, Ollokot, Lean Elk, and others, 800 men, women, and children moved northeast, hoping to seek safety with their Crow allies. Only 250 were warriors — the rest were women, children, the elderly, and the sick. On June 17, the U.S. Army and volunteer soldiers approached a Nez Perce camp on Whitebird Creek in western Idaho. When a party of six warriors bearing a flag of truce approached the soldiers, one of the volunteers fired at them, thus precipitating the Nez Perce War of 1877.

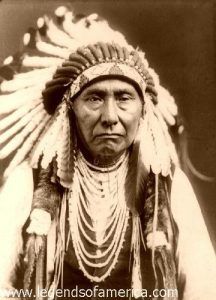

After defeating the cavalry force at the Battle of White Bird Canyon, the flight intensified, and more than a dozen more battles and skirmishes would be fought in the next several months. Fighting the army all along the trail, the number of Nez Perce was severely reduced. Just 40 miles from Canada, they were trapped at Snake Creek at the base of the Bears Paw Mountains in Montana by the U.S. Army. After a five-day fight, the remaining 431 members of the tribe were beaten, and Chief Joseph surrendered on October 5, 1877, with a speech that became famous.

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohulhulsote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men is dead.

It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are–perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead.

Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

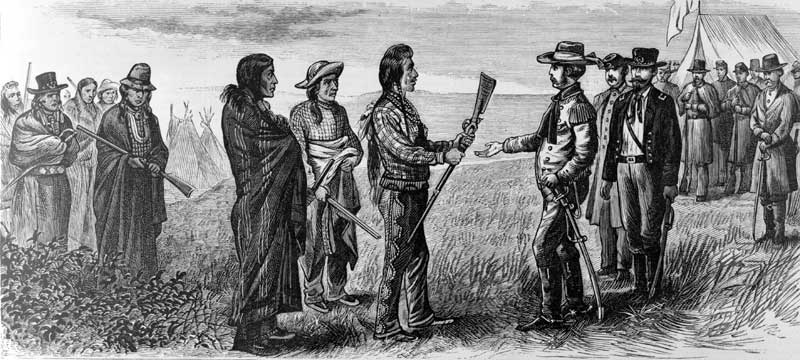

Chief Joseph Surrenders by G.M. Holland. 1877.

After their surrender, about 200-300 Nez Perce managed to avoid the army pickets and cross into Canada, while the remaining survivors were sent to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. Today, descendants of non-treaty bands live among three groups: the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in Washington, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon, and the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho.

General William Tecumseh Sherman called the Nez Perce saga “the most extraordinary of Indian wars.”

Today, their route is designated the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail by an act of Congress. With the cooperation of State Highway Departments and County Commissioners in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, over 1500 miles of federal, state, and county roads have been designated the Nez Perce National Historic Trail Auto Route. The route roughly parallels the course traveled by the Nez Perce bands during their historic 1877 flight.

The trail starts at Wallowa Lake, Oregon, then heads northeast and crosses the Snake River at Dug Bar. It enters Idaho at Lewiston and cuts across north-central Idaho, entering Montana near Lolo Pass. It then travels through the Bitterroot Valley, after which it re-enters Idaho at Bannock Pass and travels east back into Montana at Targhee Pass to cross the Continental Divide. It bisects Yellowstone National Park and then follows the Clark Fork of the Yellowstone River out of Wyoming into Montana. The trail heads north to the Bear’s Paw Mountains, ending 40 miles from the Canadian border south of Chinook, Montana.

“We, the surviving Nez Perces, want to leave our hearts, memories, and hallowed presence as a never-ending revelation to the story of the event of 1877. This trail will live in our hearts. We want to thank all who visit this sacred trail that will share our innermost feelings. Because their journey makes this an important time for the present, past, and future.”

– Frank B. Andrews, Nez Perce descendant

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2024.