Native Americans in the Civil War.

Various tribes of Native American tribes were involved in the Civil War. An estimated 20,000 Native Americans fought on both sides, with some reaching high ranks in both armies. Many more helped in support roles, such as supply, sabotage, land guides, river pilots, and spies. They participated in numerous battles, including Pea Ridge, Arkansas; Antietam, Maryland; Second Manassas, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor; and Petersburg in Virginia.

Native American allegiances varied during the Civil War but were often motivated by a common desire to protect tribal lands and lifeways. Approximately 3,503 Native Americans served in the Union Army, hoping their support would ensure the federal government to honor treaties recognizing tribal land rights.

Though exact numbers are not known, many more Native people allied with the Confederacy, in part to protect slavery in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) as well as a promise by the Confederate government that it would recognize an independent Native American country following the war’s conclusion.

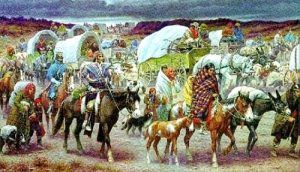

Having survived removal from their ancestral homelands in the Southeast in the 1830s and 1840s, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, and Seminole Nations signed Confederate treaties that guaranteed title to territories west of the Mississippi River. Elite tribal members’ enslavement of African Americans further motivated Southern allegiance.

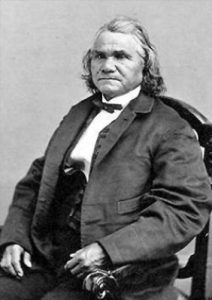

In 1861, the Cherokee Nation in the West numbered 21,000 and was experiencing its own internal civil war. The Nation was divided, with one side led by principal Chief John Ross and the other by renegade Stand Watie. Although Ross vowed to remain neutral, Confederate victories at First Manassas, Virginia, and Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, forced the Cherokee to reassess their position. The Federal government had abandoned Indian territory early on in the war, and all other Native American nations on the Cherokee borders were Confederate, leaving the Nation vulnerable to Confederate occupation. Stand Watie received a commission as a colonel in the Confederate Army and was assigned command of a battalion made up of Cherokee.

Reluctantly, on October 7, 1861, Ross signed a treaty transferring all obligations due to the Cherokee from the U.S. Government to the Confederate States. In the treaty, the Cherokee were guaranteed protection, rations of food, livestock, tools, and other goods, as well as a delegate to the Confederate Congress at Richmond. In exchange, the Cherokee would furnish ten companies of mounted men and allow the construction of military posts and roads within the Cherokee Nation. However, no Indian regiment was to be called on to fight outside Indian Territory. As a result of this agreement, the 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles, led by Colonel John Drew, was formed.

In January 1862, William Dole, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, asked Native American agents to “engage forthwith all the vigorous and able-bodied Indians in their respective agencies.” The request resulted in the assembly of the 1st and 2nd Indian Home Guard in Kansas, which included Delaware, Creek, Seminole, Kickapoo, Seneca, Osage, Shawnee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw.

Indian Home Guards.

Following the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, on March 7-8, 1862, Colonel John Drew’s Mounted Rifles defected to the Union forces in Kansas, where they joined the Indian Home Guard.

In the summer of 1862, Federal troops captured Chief John Ross, who was paroled and spent the remainder of the war in Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, proclaiming Cherokee loyalty to the Union.

With John Ross gone, Colonel Stand Watie was chosen principal chief of the Cherokee Nation and immediately drafted all Cherokee males aged 18-50 into Confederate military service. Watie was a daring cavalry officer considered a genius in guerilla warfare.

On October 23-24, 1862, Delaware, Shawnee, Osage, and other Indians attacked the Wichita Agency in Oklahoma. During the Tonkawa Massacre, which was considered a major Union victory, Native American cavalrymen killed five Confederate agents, took the Rebel flag, $1,200 in Confederate currency, 100 ponies, and burned correspondence along with the Agency buildings. During the attack on the Confederate-held agency, the Confederate Indian agent Matthew Leeper and several other whites were killed.

Colonel Stand Watie was promoted to brigadier general in May 1864 and commanded the Indian Cavalry Brigade — composed of Cherokee, Creek, Osage, and Seminole. He achieved one of his greatest successes at Pleasant Bluff, Oklahoma, on June 10, 1864, capturing the Union steamboat J.R. Williams, which was loaded with supplies valued at $120,000. At the Second Battle of Cabin Creek in Indian Territory, his cavalry brigade captured 129 supply wagons and 740 mules, took 120 prisoners, and left 200 casualties. At the war’s end, General Stand Watie was the last to surrender, laying down arms two months after General Robert E. Lee and a month after General E. Kirby Smith, commander of all troops west of the Mississippi.

The Cherokee Nation was the most negatively affected of all Native American tribes during the Civil War, its population declining from 21,000 to 15,00 by 1865. Despite the Federal government’s promise to pardon all Cherokee involved with the Confederacy, the entire Nation was considered disloyal, and those rights were revoked.

In the east, many tribes that had not been moved westward also took sides in the Civil War. The Thomas Legion, an Eastern Band of Confederate Cherokee led by Colonel William Holland Thomas, fought in the Tennessee and North Carolina mountains. Another 200 Cherokee formed the Junaluska Zouaves. Nearly all Catawba adult males served the South in the 5th, 12th, and 17th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, Army of Northern Virginia. They distinguished themselves in the Peninsula Campaign at Second Manassas, Antietam, and the Petersburg trenches. A monument in Columbia, South Carolina, honors the Catawba’s service in the Civil War.

The Pamunkey and Lumbee chose to serve the Union in Virginia and North Carolina. The Pamunkey served as civilian and naval pilots for Union warships and transports, while the Lumbee acted as guerillas. Members of the Iroquois Nation joined Company K, 5th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, while the Powhatan served as land guides, river pilots, and spies for the Army of the Potomac. During the Civil War, no distinction was made when a Native American joined the U.S. Colored Troops. Well into the twentieth century, the word “colored” included not only African Americans but Native Americans as well. Individual accounts reveal that many Pequot from New England served in the 31st U.S. Colored Infantry of the Army of the Potomac and other U.S. Colored Troops regiments.

The most famous Native American unit in the Union Army in the east was Company K of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters. Primarily comprised of Ottawa, Delaware, Huron, Oneida, Potawatomi, and Ojibwa men, they were assigned to the Army of the Potomac. Formed in 1863, the American Indian men of Company K wished to enlist earlier but had been denied. Just as General Ulysses S. Grant assumed command, Company K participated in the Battle of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania and captured 600 Confederate troops at Shand House east of Petersburg, Virginia. In their final military engagement at the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864, the Sharpshooters found themselves surrounded with little ammunition. A lieutenant of the 13th U.S. Colored Troops described their actions as “splendid work. Some of them were mortally wounded, and drawing their blouses over their faces, they chanted a death song and died – four of them in a group.”

The mentality of Company K embodied that of many of the Native Americans who chose to serve — by demonstrating loyalty on the battlefield, they hoped to be rewarded. They also saw war service as a means to end discrimination and relocation from ancestral lands to western territories.

Instead, the United States government continued to implement policies that removed American Indians from their ancestral homes. Battles of the ongoing American Indian Wars at times collided with those of the Civil War as the great push of Westward Expansion continued during the clash of the Union and Confederacy. While the war raged and African Americans were proclaimed free, the U.S. government continued its policies of pacification and removal of Native Americans.

At the war’s end, General Ely S. Parker, a member of the Seneca tribe and General Ulysses S. Grant’s military secretary, drew up the articles of surrender that General Robert E. Lee signed at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Parker, a trained lawyer once rejected for army service because of his race, was the highest-ranking American Indian in the Union army, a lieutenant colonel.

At Appomattox, General Lee is said to have remarked to Parker: “I am glad to see one real American here,” to which Parker replied, “We are all Americans.”

The war exacted a terrible toll on Indigenous people. One-third of all Cherokee and Seminole in Indian Territory died from violence, starvation, and war-related illness. Despite their sacrifice, American Indians would discover that their tribal lands were even less secure after the war.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

City of Alexandria, Virginia

National Museum of the American Indian

National Museum of Civil War Medicine

Wikipedia