Trail of Tears painting by Robert Lindneux.

Long time we travel on way to new land. People feel bad when they leave old nation. Women cry and make sad wails. Children cry and many men cry, and all look sad, like when friends die, but they say nothing and just put heads down and keep on go towards West. Many days pass, and people die very much. We bury close by Trail.

— Survivor of the Trail of Tears

As part of President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Policy of 1830, the Cherokee Nation was forced to give up its lands east of the Mississippi River and migrate to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma.)

During the forced march, over 4,000 of the 15,000 Indians died of hunger, disease, cold, and exhaustion. In the Cherokee language, the event is called Nunna daul Tsuny — “the trail where they cried.”

The Indian Removal Act was spawned by the rapidly expanding population of new settlers, creating tensions with the American Indian tribes. Even Thomas Jefferson, who often cited the Great Law of Peace of the Iroquois Confederacy as the model for the U.S. Constitution, supported Indian removal as early as 1802.

However, Jefferson’s policy also allowed Indians to remain east of the Mississippi River as long as they became “civilized,” meaning they were to settle in one place, adopt democracy, and divide communal land into private property to be utilized for farming.

Also, in 1802, Georgia gave up its claims to land in the western part of the state to the U.S. Government. These lands became the states of Alabama and Mississippi. In exchange, Georgia expected that the government would remove the Indian tribes, thus allowing the State of Georgia complete control of the land within its borders.

When this didn’t immediately happen, white settlers began to resent the Cherokee. Pressure was put on the tribe to move voluntarily. However, their homeland, overlapping Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama, had been their place of residence for generations, and they did not want to make a move.

In 1819, Georgia appealed to the U.S. government to remove the Cherokee from Georgia’s lands, and when the appeal failed, attempts were made to purchase the territory. The following year, in 1820, the Cherokee Nation was founded, which included elected public officials and a governmental system modeled after the United States. John Ross was elected its principal chief, and tribal members were elected to its Senate and House of Representatives. One of the new government’s first tasks was to enact a law that forbade the sale of any of the Cherokee lands on punishment of death.

Old Cherokee National Capitol Building.

In 1825, Ross and Major John Ridge, the speaker of the Cherokee National Council, established a capital near present-day Calhoun, Georgia. A written constitution was drafted two years later, declaring the Cherokee Nation a sovereign and independent nation.

When gold was discovered in White County, Georgia, in 1828, the state began to push even harder to remove the Indians. The Georgia legislature soon outlawed the Cherokee government and confiscated tribal lands. When the Cherokee appealed for federal protection, President Andrew Jackson rejected them.

When the State of Georgia moved to extend state law over Cherokee lands in 1830, the Cherokee Nation took the matter before the U.S. Supreme Court. A year later, the court ruled that the Cherokee were not a sovereign and independent nation. Another court ruling in 1832 stated that Georgia could not impose laws in Cherokee territory since only the national government had authority in Indian affairs.

But, these court rulings would make no difference, as while the cases were before the courts, President Andrew Jackson authorized the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Once an ally of the Cherokee, Jackson was fully committed to the policy of Indian removal, which provided for the government to negotiate removal treaties, exchanging Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. The first treaty was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek with the Choctaw, which moved some 14,000 Choctaw west from the Mississippi River along the Red River. However, about 7,000 of the Choctaw tribe remained in Mississippi.

The Jackson Administration began to put pressure on the Cherokee and other tribes to sign treaties of removal, but the Cherokee rejected any proposals. However, when Jackson was reelected in 1832, some Cherokee believed removal was inevitable. A Treaty Party, led by Major John Ridge, believed that it was in the best interest of the Cherokee Nation to get the best possible terms from the U.S. government. Cautiously, Ridge began unauthorized talks with the Jackson administration.

However, Chief John Ross and most Cherokee people opposed removal. In 1832, Ross canceled the tribal elections, the Council impeached Ridge, and a member of the Ridge Party was murdered. The “Treaty Party” responded by forming their council, representing only a small minority of the Cherokee people. Both the Ross government and the Ridge Party sent independent delegations to Washington.

In the meantime, the State of Georgia was so sure that the Cherokee would be removed they began holding lotteries to divide up the Cherokee tribal lands among white Georgians.

In 1835, Jackson appointed a treaty commissioner named Reverend John F. Schermerhorn, who offered to pay the Cherokee Nation 4.5 million dollars to move. In October 1835, the Cherokee Nation rejected the terms. Chief Ross and John Ridge traveled to Washington to open new negotiations but were turned away and told to deal with Schermerhorn.

Schermerhorn soon organized a group of pro-removal members and issued a summons for the Cherokee members’ attendance. Only about 500 of the Cherokee (out of thousands) attended, but the Treaty of New Echota was agreed to. This treaty allowed the Cherokee Nation to cede its lands in exchange for $5,700,000 and new lands in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Though more than nine-tenths of the tribe repudiated the actions and were not signed by a single elected tribal official, Congress ratified the treaty on May 23, 1836.

Chief Ross and the Cherokee National Council maintained that the document was a fraud and presented a petition with more than 15,000 Cherokee signatures to Congress in the spring of 1838. Other white settlers also were outraged by the questionable legality of the treaty. On April 23, 1838, Ralph Waldo Emerson appealed to Jackson’s successor, President Martin Van Buren, urging him not to inflict “so vast an outrage upon the Cherokee Nation.” But it was not to be.

As the deadline for voluntary removal on May 23, 1838, approached, President Van Buren appointed General Winfield Scott to lead the forcible removal operation. Commanding some 7,000 troops, Scott arrived in Georgia on May 26, beginning a forcible evacuation at gunpoint. An estimated 17,000 Cherokee, along with about 2,000 black slaves, were forced to move over the next three weeks. The swift and brutal process drove men, women, and children out of their homes, sometimes with only the clothes on their backs. They were then gathered in camps where conditions were terrible. Many Cherokee died while waiting in the camps, where food and supplies were limited and disease was rampant.

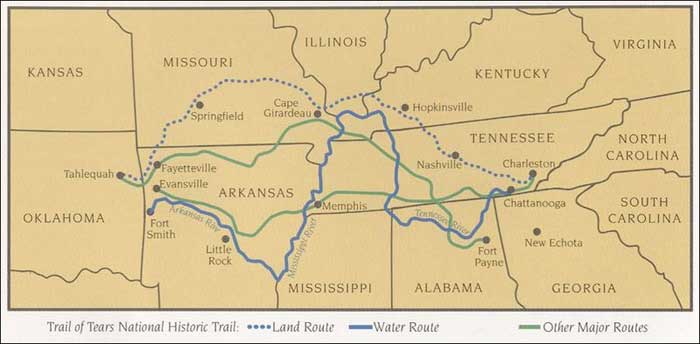

Trail of Tears Routes, National Park Service.

Fortunately, about 1,000 Cherokee escaped to the North Carolina mountains. Others who lived on individually owned land (rather than tribal domains) were not subject to removal. Those lucky enough not to have been evacuated would eventually form new tribal groups, including the Eastern Band Cherokee, based in North Carolina, that still exist today.

Two routes were utilized to move thousands of Cherokee. The first of three detachments, totaling about 2,800 people, left on June 6 by steamboats and barges on the Tennessee River at present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee. After several transfers, including a short railroad detour, they were at the mouth of Salisaw Creek near Fort Coffee on June 19, 1838. The other two groups suffered more because of a severe drought and disease (especially among the children), and they did not arrive in Indian Territory until the end of the summer.

The rest of the Cherokee were not so fortunate and were forced to travel to the Indian Territory on overland trails. For those forced to march by land, the Cherokee petitioned for a delay until cooler weather would make the journey less hazardous. Chief Ross, who had finally accepted defeat, also managed to have the remainder of the removal turned over to the supervision of the Cherokee Council.

Organized into detachments of 700 to 1,600 people, each headed by a conductor and an assistant appointed by Chief John Ross, the marches began on August 28, 1838, and consisted of 13 groups.

The most commonly used overland route followed a northern alignment, while other detachments followed more southern routes and other slight variations. The northern route began in Tennessee and crossed southwestern Kentucky and southern Illinois. After crossing the Mississippi River north of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, these detachments trekked across southern Missouri and northwest Arkansas before arriving in Oklahoma near present-day Westville.

Along the 2,200-mile journey, road conditions, illness, cold, and exhaustion took thousands of lives, including Chief John Ross’ wife, Quatie. Though the federal government officially stated some 424 deaths, an American doctor traveling with one of the parties estimated that 2,000 people died in the camps and another 2,000 along the trail. Other estimates have been stated that conclude that almost 8,000 of the Cherokee died during the Indian Removal.

When they finally reached Oklahoma, U.S. troops from Fort Gibson and the Arkansas River often met the groups. Most of the Cherokee went to live with those who had already arrived, settling near present-day Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Problems quickly developed among the new arrivals and those Cherokee who had already settled. Reprisals were taken against the group that had signed the Treaty of New Echota, leading to the assassinations of Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot. Only Stand Watie eluded his assassins.

As these problems were resolved, the Cherokee adapted to their new homeland and reestablished their system of government. The population of the Cherokee Nation eventually rebounded, and today, the Cherokee are the largest American Indian group in the United States.

Ultimately, the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole Nation members suffered the same fate as the Cherokee.

Considered one of the most regrettable episodes in American History, the U.S. Congress designated the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail in 1987. Commemorating the 17 Cherokee detachments, the trail encompasses about 2,200 miles of land and water routes and traverses portions of nine states.

The National Park Service administers the Trail of Tears in partnership with other federal agencies, state and local agencies, non-profit organizations, and private landowners.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

“I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes and driven at the bayonet point into the stockades. And in the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning, I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and forty-five wagons and started toward the west… On the morning of November 17, we encountered a terrific sleet and snowstorm with freezing temperatures, and from that day until we reached the end of the fateful journey on March 26, 1839, the sufferings of the Cherokees were awful. The trail of the exiles was a trail of death. They had to sleep in the wagons and on the ground without fire. And I have known as many as twenty-two of them to die in one night of pneumonia due to ill-treatment, cold, and exposure…”

— Private John G. Burnett, 2nd Regiment, 2nd Brigade, Mounted Infantry, Cherokee Indian Removal 1838-39

Also See:

Cherokee – Forced From Their Homeland on the Trail of Tears

Chief John Ross of the Cherokee Nation