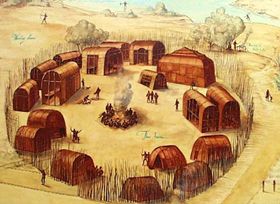

Powhatan village.

The Powhatan tribe, also spelled Powatan and Powhatan, is a Virginia Indian tribe that dominated eastern Virginia when the English settled Jamestown in 1607. Their name means “falls in a current of water.” When European settlers arrived in the Chesapeake Bay, the region was occupied by approximately 14,000-21,000 Powhatan Indians, concentrated in some 200 villages along the rivers. They were also known as Virginia Algonquian, as they spoke an eastern Algonquian language known as Powhatan.

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a paramount chief named Wahunsunacawh created a powerful organization by affiliating 30 tribes, including not only the Powhatan but also the Arrohateck, Appomattoc, Pamunkey, Mattaponi, Chiskiack, and others. This organization was known as the Powhatan Confederacy. Wahunsunacawh came to be known by the English as “Chief Powhatan.” Though all of the tribes within the Confederacy had their own chief, all paid tribute to Chief Powhatan.

Their territory included the tidewater section of Virginia from the Potomac River south to the divide between the James River and Albemarle Sound. It extended into the interior as far as the falls of the principal rivers about Fredericksburg and Richmond. They also occupied the Virginia counties east of Chesapeake Bay and possibly included some tribes in lower Maryland.

The Powhatan tribes were visited by some of the earliest explorers of the period of discovery, and in 1570, the Spaniards established a Jesuit mission, which had but a brief existence. Fifteen years later, the southern tribes were brought to the notice of the English settlers at Roanoke Island, but little was known of them until the establishment of the Jamestown settlement in 1607.

The Powhatan were not only hunters and gatherers but were also farmers, cultivating several varieties of maize, beans, certain kinds of melons or pumpkins, roots, and 2-three types of fruit trees. They lived in oblong houses with rounded roofs, which varied in length up to 36 yards. Many of their towns were enclosed with palisades, consisting of posts planted in the ground and standing 10 or 12 feet high. A triple stockade was sometimes made when great strength and security were required. These enclosing walls sometimes encompassed the whole town; in other cases, only the chief’s house, the burial house, and the more important dwellings were thus surrounded.

They believed in many minor deities, worshipping things of nature that could harm them, such as fire, water, lightning, and thunder. The office of chief was hereditary through the female line, passing first to the brothers, if there were any, and then to the male descendants of sisters, but never in the male line.

Although early interactions between the English and the Powhatan were sometimes violent and exploitative on both sides, leaders of both peoples realized the mutual benefit derived from peaceful relations. The marriage of Powhatan’s daughter, Pocahontas, to settler John Rolfe in 1614 ensured a few years of peace. However, with the death of Pocahontas in 1617 and the death of Powhatan a year later, the peace came to an end.

When Chief Powhatan died, he was succeeded by his brother Opechancanough. Unfortunately for the English settlers, Opechancanough was the deadly foe of the whites and at once began secret preparations for a general uprising. On March 22, 1622, a simultaneous attack was made along the whole frontier, in which 347 of the English were killed in a few hours, and every settlement was destroyed except those immediately around Jamestown, where the whites had been warned in time.

As soon as the English could recover from the first shock, a war of extermination was begun against the Indians. It was ordered that three expeditions should be undertaken yearly against them so that they might have no chance to plant their corn or build their wigwams, and the commanders were forbidden to make peace upon any terms whatever. A large number of Indians were at one time induced to return to their homes by promises of peace, but all were massacred in their villages, and their houses burned. The ruse was attempted a second time but was unsuccessful. The war lasted 14 years until both sides were exhausted when peace was made in 1636. The greatest battle was fought in 1625 at Pamunkey, where Governor Francis Wyatt defeated nearly 1,000 Indians and burned their principal village.

Powhattan Warrior by John White.

Peace lasted until the spring of 1644 when Opechancanough led one last uprising, killing 300-500 colonists. This time, however, he was captured. While imprisoned at Jamestown, he was shot by a guard and later died of his wounds. His death broke the Confederacy, and the tribes made separate peace treaties. They were put upon reservations, which were constantly reduced in size by sale or by confiscation upon slight pretense.

About 1656, the Cherokee from the mountains invaded the lowlands. The Pamunkey chief, with 100 of his men, joined the whites in resisting the invasion, but they were almost all killed in a desperate battle on Shocco Creek near Richmond. By 1669, the population of Powhatan Indians in the area had dropped to about 1,800, and by 1722, many of the tribes comprising the empire of Chief Powhatan were reported extinct.

In 1675, some Conestoga, driven by the Iroquois from their country on the Susquehanna River, entered Virginia and committed several depredations. The Virginian tribes were accused of these acts, and several unauthorized expeditions were led against them by Nathaniel Bacon, resulting in several Indians being killed and villages destroyed. The Indians, at last, gathered in a fort near Richmond and made preparations for defense. In August 1676, the fort was stormed, and the whites massacred men, women, and children. The adjacent stream was known as Bloody Run after this circumstance. The scattered survivors asked for peace, granted on the condition of an annual tribute from each village.

In 1722, a treaty was made at Albany, New York, by which the Iroquois agreed to cease their attacks upon the Powhatan tribes, who were represented at the conference by four chiefs. With the Treaty of Albany, the history of the Powhatan tribes practically ceased, and the remnants of the confederacy dwindled nearly to extinction.

About 1705, the Powhatan were described as “almost wasted.” They then had 12 villages, 8 of which were on the Eastern shore, the only one of consequence being Pamunkey, with about 150 souls. Those on the Eastern shore remained until 1831, when the few surviving individuals, having become so much mixed with African-American blood as to be hardly distinguishable, were driven off during the excitement caused by the slave rising under Nat Turner. Some of them had previously joined the Nanticoke.

Despite all these odds, however, the Powhatan have survived. Today, there are eight Powhatan Indian-descended tribes recognized by the State of Virginia. Most of these tribes are still working to obtain Federal recognition. Another band called the Powhatan Renape to have official headquarters in New Jersey. The state also recognizes these people.

The Powhatan Indians speak English today as their original language has long been lost. However, efforts are currently being made to reconstruct it.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See:

Chief Powhatan – Wahunsunacawh

Opechancanough – Powhatan Chief

See Sources.