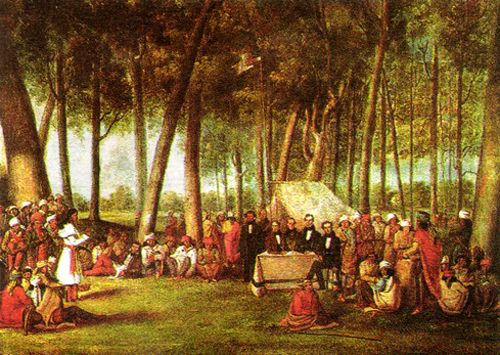

Kee-Waw-Nay Potawatomi Village, council between Potawatomi leaders and U.S. government representatives on July 21, 1837, to settle details for the impending removal of the Potawatomi from northern Indiana. Painted by George Winters.

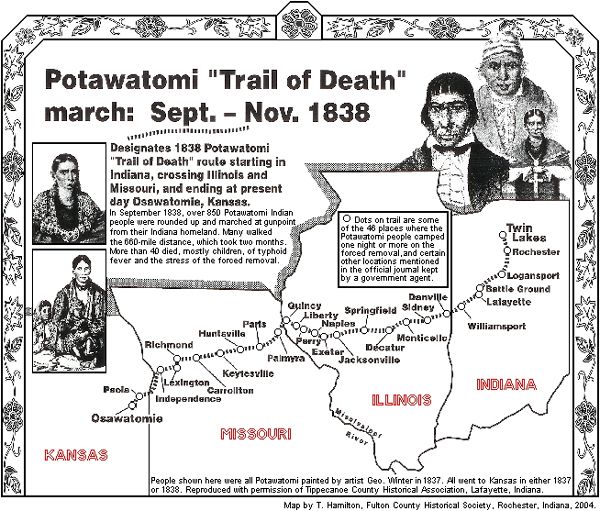

In September 1838, 859 Potawatomi Indians were forced from their homeland near Plymouth, Indiana, and made to march 660 miles to present-day Osawatomie, Kansas. At gunpoint, the tribe began the march on September 4, 1838. During the two-month journey, 42 members of the tribe, mostly children, died of typhoid fever and the stress of the forced removal, and about as many had escaped along the journey. When they arrived in Osawatomie, Kansas, that November, there were only 756 of the tribe left.

Native American tribes began to be forced from their homelands in 1830 when the Federal Government passed the Indian Removal Act. As more and more European immigrants arrived in the United States, the government determined that more room was needed for them, pushing the Indians to unpopulated lands west of the Mississippi River. The Indian Removal Act was explicitly enacted to remove the Five Civilized Tribes from the southeast. Later, it would lead to multiple treaties with other tribes east of the Mississippi River.

Negotiations with various Potawatomi bands began in 1832 to move them from their homelands in Indiana to lands in Kansas. While many complied over the next several years, Chief Menominee and his band at Twin Lakes, Indiana, refused to sign the treaties.

By August 1838, most of the Potawatomi bands had migrated peacefully to their new lands in Kansas, but Chief Menominee’s band stayed at their Twin Lakes village. Hundreds of others who did not want to leave their homeland joined Menominee’s band, which grew from four wigwams in 1821 to 100 in 1838. As a result, Indiana Governor David Wallace ordered General John Tipton to mobilize the state militia to remove the tribe forcibly.

On August 30, General Tipton and 100 soldiers arrived at the Twin Lakes Village and began to round up the tribe, burning their crops and homes to discourage them from trying to return. Five days later, on September 4, the march began with more than 850 Indians and a caravan of 26 wagons to help transport their goods. Chief Menominee and two other chiefs, No-taw-kah and Pee-pin-oh-waw, were placed in a horse-drawn jail wagon while their people walked or rode horseback behind them. Each day, the trek began at 8:00 a.m. and continued until 4:00 p.m., when they rested for the evening and were given their only meal of the day.

Father Benjamin M. Petit

The tribe was accompanied by a young priest, Father Benjamin M. Petit. Along the way, he ministered to the tribe spiritually, emotionally, and physically, tending to the sick. That fall, there was a terrible drought, and unfortunately, what little water they found was usually stagnant, causing many of them to get sick with what was probably typhoid. As more and more died along the way, Father Petit baptized the dying children, blessed each grave when someone died, and conducted Mass each day, though he also grew sick along the journey.

On October 13, 1838, while traveling along the Osage River in Missouri, he wrote a letter describing the march to Bishop Simon Brute, Vincennes, Indiana.

“The order of march was as follows: The United States flag, carried by a dragoon; then one of the principal officers, next the staff baggage carts, then the carriage, which during the whole trip was kept for the use of the Indian chiefs, then one or two chiefs on horseback led a line of 250 to 300 horses ridden by men, women, children in single file, after the manner of savages.

On the flanks of the line at equal distance from each other were the dragoons and volunteers, hastening the stragglers, often with severe gestures and bitter words. After this cavalry came a file of forty baggage wagons filled with luggage and Indians. The sick were lying in them, rudely jolted, under a canvas which, far from protecting them from the dust and heat, only deprived them of air, for they were as if buried under this burning canopy – several died.”

Across the great prairies of Illinois, they marched, crossed the Mississippi River at Quincy, Missouri, made their way along the rivers in Missouri, and entered Kansas Territory south of Independence, Missouri. When they arrived at present-day Osawatomie, Kansas, on November 4, 1838, 42 of the 859 Potawatomi had died. Despite the government’s promise, Winter was coming on, and there were no houses. The Potawatomi were upset, and Father Petit, who was very sick then, stayed with them for a few weeks. He arranged with Jesuit Father Christian Hoecken, who operated St. Mary’s Sugar Creek Mission, for the Indians to move to the site. Located about 20 miles south of Osawatomie, near present Centerville, Kansas, the mission had been established the previous year for a group of Potawatomi, including Chiefs Kee-wau-nay and Nas-waw-kay, who had relocated voluntarily.

Map courtesy Fulton County Historical Society, Rochester, Indiana.

A few weeks later, on January 2, 1839, Father Petit set out for Indiana, accompanied by Abram “Nan-wesh-mah” Burnett. At the time, Burnett had to hold Petit on his horse, as the priest was sick with sores all over his body. When they reached Jefferson City, Missouri, Petit was so sick he could no longer ride a horse and was forced to ride in a wagon. The pair reached the Jesuit seminary in St. Louis, Missouri, on January 15. Father Petit was too sick to travel further. He died at the seminary on February 10, 1839, at the age of 27. He was initially buried in the Jesuit Cemetery in St. Louis, but years later, in 1856, he was re-interred at Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. Today, many of the Potawatomi feel that Father Petit is a saint.

The St. Mary’s Sugar Creek Mission was the actual end of the Potawatomi Trail of Death. Though they still had no houses, they found shelter along the creek bank’s steep, rocky walls, where they could hang blankets and keep warm with campfires. Thus, they spent that first winter in Kansas. Later, they built wigwams and log cabins and lived at the mission for the next ten years.

Three years after their arrival, Mother Rose Philippine Duchesne came to the mission in 1841, where she taught school to the young members of the tribe. She established the first Indian school for girls west of the Mississippi River. By then, she was 72 years old, and her health was failing. Unable to do much work, she dedicated herself to a contemplative prayer ministry, urging the Indians to name her Quah-kah-ka-num-ad, “Woman-Who-Prays-Always.” She was canonized in 1988 as the first female saint west of the Mississippi River.

The Potawatomi of the Woods Mission Band remained in eastern Kansas for ten years. In 1848 they moved further west to St Marys, Kansas, close to the Prairie Band Potawatomi Reservation at Mayetta, Kansas. During their years at the mission, more than 600 of the Potawatomi died, many of them shortly after their arrival. Chief Alexis Menominee died on April 15, 1841, at the age of 50. All are buried at the site.

In 1861, the Potawatomi were offered a new treaty that gave them land in Oklahoma. Those who signed this treaty became the Citizen Band Potawatomi because they were given U.S. citizenship. Today, their headquarters is in Shawnee, Oklahoma.

Though the mission is no longer there, the site commemorates the Potawatomi struggle at the St. Philippine Duchesne Memorial Park. In the 1980s, the Eastern Kansas Diocese bought 450 acres where the original Sugar Creek Mission stood. The St. Philippine Duchesne Memorial Park was dedicated in 1988 with a large circular altar and a 30-foot tall metal cross. The park also features seven wooden crosses with metal plaques to honor those who died there and several interpretive signs that display information about the Potawatomi Indians and the original mission buildings.

Today, the Potawatomi Trail of Death has been declared a Regional Historic Trail. Since 1988, a commemorative caravan has followed the same trail every five years, starting at the Chief Menominee statue south of Plymouth, Indiana, and ending at the St. Philippine Duchesne Memorial Park near Centerville, Kansas.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

St. Philippine Duchesne Memorial Park near Centerville, Kansas.

Also See:

Cherokee – Forced From Their Homeland on the Trail of Tears

Native Americans – First Owners of America