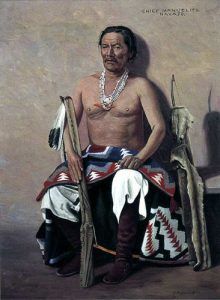

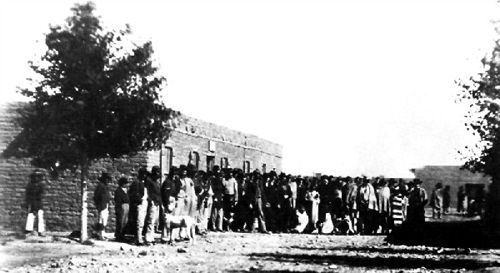

Navajo Prisoners taking the “Long Walk”, touch of color LOA.

“Officials called it a reservation, but to the conquered and exiled Navajos, it was a wretched prison camp.” — David Roberts, Smithsonian Magazine

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, was an Indian removal effort of the United States government in 1863 and 1864. Early relations between Anglo-American settlers of New Mexico were relatively peaceful, but the peace began to disintegrate following the killing of a respected Navajo leader named Narbona in 1849. By the 1850s, the U.S. government had begun establishing forts in Navajo territory, namely Fort Defiance, Arizona, and Fort Wingate, in northeast New Mexico. Further, the Bonneville Treaty of 1858 reduced the extent of land, and the relatively pro-Navajo local U.S. Army leader and Indian agent was reassigned to West Point.

By the 1860s, as more and more Americans pushed westward, they met increasingly fierce resistance from the Mescalero Apache and Navajo people, who fought to maintain control of their traditional lands and way of life. Under the leadership of the new commander of Fort Defiance, William T. H. Brooks, the Navajo, and the U.S. Army began a destructive cycle of raids and counter-raids culminating in the near-sacking of Fort Defiance by approximately 1,000 Navajo warriors under the leadership of Manuelito and Barboncito on April 30, 1860.

Despite another treaty signed on February 15, 1861, relations quickly got worse when a dispute over a horse race of questionable fairness resulted in the massacre of 30 Native Americans on the orders of Colonel Manuel Chaves, commander of Fort Wingate. Following this massacre, which took place on September 22, 1861, military leaders began drafting plans to send the local Navajo on the Long Walk.

Originated by General James H. Carleton, New Mexico’s U.S. Army commander, the plan called for the removal of the Navajo from their native lands, including areas in northeastern Arizona, through western New Mexico, and north into Utah and Colorado.

To accomplish their plan, the U.S. Army made war on the Mescalero Apache and Navajo Indian tribes, destroying their fields, orchards, houses, and livestock. Before the Indians were even defeated, Congress authorized the establishment of Fort Sumner, New Mexico, at Bosque Redondo on October 31, 1862, a space 40 miles square.

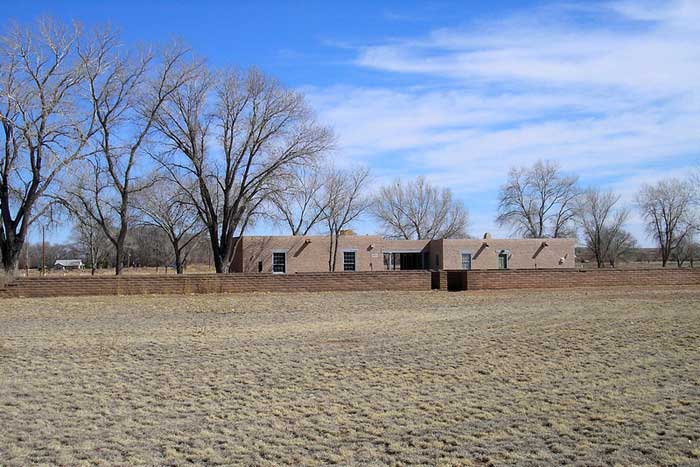

Though some officers specifically discouraged the selection of Bosque Redondo as a site because of its poor water and minimal provisions of firewood, it was established anyway. It was to be the first Indian reservation west of Oklahoma. The plan was to turn the Apache and Navajo into farmers on the Bosque Redondo with irrigation from the Pecos River. They were also to be “civilized” by attending school and practicing Christianity.

Bosque Redondo Reservation

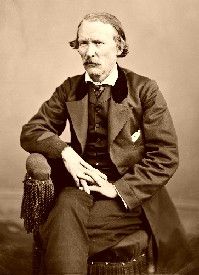

The Apache and Navajo, who had survived the army attacks, were starved into submission. During a final standoff at Canyon de Chelly, the Navajo surrendered to Kit Carson and his troops in January 1864. Following orders from his U.S. Army commanders, Carson directed the destruction of their property and organized the Long Walk to the Bosque Redondo reservation, already occupied by Mescalero Apache.

Soon, 8,500 men, women, and children were marched almost 300 miles from northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico to Bosque Redondo, a desolate tract on the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico. Traveling in harsh winter conditions for almost two months, about 200 Navajo died of cold and starvation. More died after they arrived at the barren reservation. The forced march, led by Kit Carson, became known by the Navajo as the “Long Walk.”

Some Navajo managed to escape the Walk, variously surviving in the territory of the Chiricahua Apache, the Grand Canyon, Navajo Mountain, and in Utah.

The ill-planned site, named for a grove of cottonwoods by the river, turned into a virtual prison camp for the Indians. The brackish Pecos water caused severe intestinal problems in the tribe, and disease ran rampant. Armyworm destroyed the corn crop, and the wood supply at the Bosque Redondo was soon depleted. Most of the Mescalero Apache eluded their military guards and abandoned the reservation on November 3, 1865; but, for the Navajo, another three years passed before the United States Government recognized that their plan for Americanizing the Navajo had failed.

Bosque Redondo was hailed as a miserable failure, the victim of poor planning, disease, crop infestation, and generally poor conditions for agriculture. The Navajo finally acknowledged sovereignty in the historic treaty of 1868.

The Navajo returned to their land along the Arizona-New Mexico border hungry and in rags. Though their territory had been reduced to an area much smaller than what they had occupied before the departure to Bosque Redondo, they were one of the few tribes that were allowed to return to their native lands. The U.S. government issued them rations and sheep, and within a few years, the Navajo multiplied their livestock numbers and began to prosper once again.

Today the Navajo Nation is the largest Native American community in the United States.© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2023.

“Cage the badger, and he will try to break from his prison and regain his native hole. Chain the eagle to the ground – he will strive to gain his freedom, and though he fails, he will lift his head and look up at the sky, which is home – and we want to return to our mountains and plains, where we used to plant corn, wheat, and beans.”

— Written by a Navajo in 1865

Also See:

Kit Carson – Legend of the Southwest