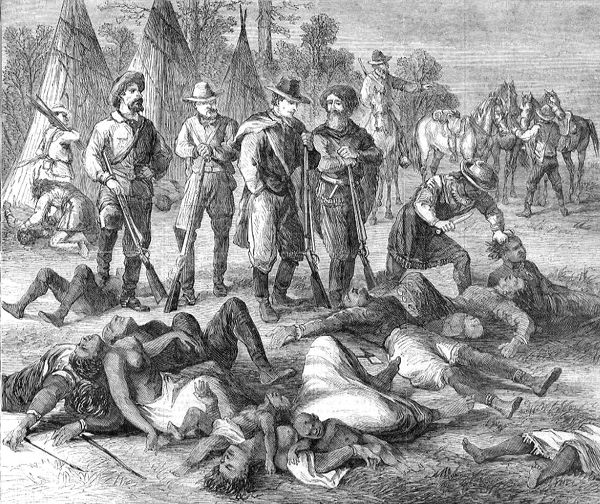

“The greatest slaughter of Indians ever made by U.S. Troops.”

–– Lieutenant Gus Doane, commander of F Company

The Marias Massacre is a little-known one-sided incident in Montana on January 23, 1870. Though receiving little attention in history, the massacre, which killed some 200 Piegan Indians, primarily women, and children, was described by one company commander as “the greatest slaughter of Indians ever made by U.S. troops.”

Before this event, relations between the Blackfeet Confederacy comprised the Blackfeet, Blood, and Piegan tribes, and the white settlers had been hostile for several years. Amidst low-level hostilities in 1869, a young warrior named Owl Child stole several horses from Malcolm Clarke, a white trader. Afterward, Clarke tracked down Owl Child and beat him in front of his camp for the offense. Humiliated, Owl Child, with a band of rogue Piegans, sought revenge and killed Clarke.

The killing inflamed the public, which caused General Philip Sheridan to send out a band of cavalry led by Major Eugene Baker to track down and punish the offending party.

On January 23, 1870, the cavalry received a scouting report that the Piegan, led by Mountain Chief, was camped along the Marias River. At first light, 200 dismounted U.S. cavalrymen lay spread out in ambush along the snowy bluffs overlooking the Marias River. As they awaited the command to fire, the camp chief came out of his lodge, walking toward the bluffs, waving a safe-conduct paper. It was not Mountain Chief who had been forewarned and had already left the area. Instead, it was Piegan leader Heavy Runner who had enjoyed friendly relations with the white men. When an Army scout named Joe Kipp shouted that this was the wrong camp, he was threatened with silence. Another scout, Joe Cobell, then fired the first shot, killing Heavy Runner and the massacre ensued.

The site of the Marias Massacre, photo by Dean Hellinger

In those early morning hours, the Indian camp was unprotected as most men were out hunting. Bullets riddled the lodges, collapsing some into smoking fire pits and suffocating the half-awake victims. When the carnage was over, 173 lay dead – primarily women, children, and the elderly. 140 others were captured, later to be turned loose without horses, adequate food, and clothing. As the refugees made their way to Fort Benton, some 90 miles away, many of them froze to death.

In the meantime, Major Eugene Baker led his troops downstream to find the actual target designated clearly in his orders. However, by the time they arrived, Mountain Chief and his band had fled to safety in nearby Canadian territory.

Only one cavalryman died in the massacre after falling off his horse and breaking his leg. Lieutenant Gus Doane, commander of F Company, described the massacre as “the greatest slaughter of Indians ever made by U.S. troops.”

Afterward, a brief storm of outraged protest occurred in Congress and the eastern press. However, General William Sherman deflected a public inquiry by silencing the protests of General Alfred Sully, the Bureau of Indian Affairs superintendent of Montana Indians, and Lieutenant William Pease, the Piegan Indian Agent who had reported the damning body count. Sherman responded by issuing a press release denying military guilt and insisting that most of the dead Piegans were warriors in Mountain Chief’s camp.

Many blamed Major Baker, a known alcoholic, for the massacre and failure to capture Mountain Chief’s men. However, General Sheridan expressed his confidence in Baker’s leadership in the subsequent controversy. Between Sheridan and Sherman’s statements, an official investigation into the incident never occurred.

Though the incident was as significant as many others, such as the Bear River, Sand Creek, and Washita Massacres, history has overlooked this incident, with little mention of the event in the books and journals of the past. No sign or monument marks the site of the mass grave of the Piegan victims.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2022.

Also See:

The Blackfeet Indians – “Real” People of Montana

Myths & Legends of the Blackfeet