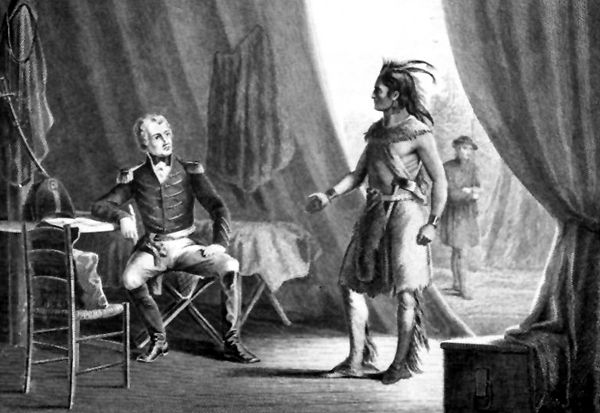

Creek surrender to President Jackson

Signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830, the Indian Removal Act authorized the president to grant unsettled lands west of the Mississippi River in exchange for Indian lands within existing state borders.

Before becoming president, Jackson had been a long-time proponent of Indian removal. In 1814, he commanded the U.S. military forces that defeated a faction of the Creek during the Creek War of 1813-1814. After their defeat, the Creek Nation lost 22 million acres of land in southern Georgia and central Alabama.

The following year, in 1815, and again in 1818, Jackson marched against the Seminole Indians in Spanish-held Florida to punish them for their practice of harboring fugitive slaves. As a result of the attack in 1818, the Spanish government realized that it could not defend Florida against the United States. The following year, Spain sold Florida to the United States.

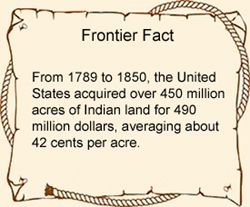

In addition to leading the charge against some tribes, Jackson was also instrumental in negotiating nine out of eleven treaties between 1814 and 1824. They divested their eastern lands in exchange for lands in the west. Of those tribes who signed treaties during this time, they did so for strategic reasons – hoping to retain control over part of their territory by ceding some portions; and to protect themselves from harassment by white settlers.

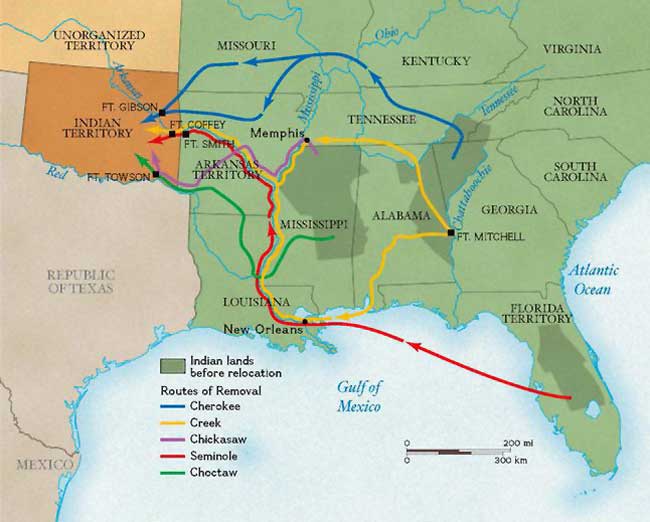

As a result of these treaties, the Federal Government gained control over three-quarters of Alabama and Florida and parts of Georgia, Tennessee, Mississippi, Kentucky, and North Carolina. However, this “voluntary” Indian migration resulted in only a small number of Creek, Cherokee, and Choctaw Indians moving westward. Many others resisted the relocation policy, and the Creek and Seminole waged war to protect their territory.

But, as more and more white settlers made their way to the South, their protests became louder. They began to pressure the Federal Government to acquire more Indian lands to expand their farms to raise cotton and remove the Indians who they felt were obstructing progress. The tribes became even more of an “obstacle” after gold was discovered in Georgia, and the pressure on the government increased.

In the meantime, several tribes began to adopt white practices, such as farming, education, and holding slaves, to ward off hostility and co-exist with the new settlers. In the end, however, their efforts would be for naught.

When Andrew Jackson was elected president in 1828, the policy of Indian Removal became even more prevalent. Early in 1829, he called for an Indian Removal Act in his first year in office and worked quickly towards that goal. Even though there was significant opposition by many Christian missionaries, and others including future president Abraham Lincoln, and Tennessee Congressman Davy Crockett, most European Americans favored the passage of the Indian Removal Act. In the south, the settlers were particularly eager to rid themselves of the “Five Civilized Tribes,” especially the state of Georgia, which was involved in a contentious jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokee Nation.

After a bitter debate in Congress, the Indian Removal Act was passed on May 26, 1830. It was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson two days later, on May 28. In his Second Annual Message to Congress on December 6, 1830, Jackson’s comments on Indian removal begin with these words: “It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation. Two important tribes accepted the provision made for their removal at the last session of Congress, and it is believed that their example will induce the remaining tribes to seek the same obvious advantages.”

While Native American removal was supposed to be voluntary, in practice, tremendous pressure was put on Native American leaders to sign removal treaties. Some Native American leaders who had previously resisted removal soon began to reconsider their positions, especially after Jackson’s landslide re-election in 1832. Affected tribes included the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and the Seminole.

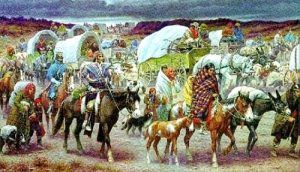

The Removal Act paved the way for the reluctant and often forcible emigration of tens of thousands of American Indians to the West. The first removal treaty signed after the Removal Act was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek on September 27, 1830, in which the Choctaw in Mississippi ceded their land east of the Mississippi River. The Treaty of New Echota was signed in 1835, which resulted in the removal of the Cherokee in the fall and winter of 1838 and 1839.

During the removal, approximately 4,000 Cherokee died on this forced march, which became known as the “Trail of Tears.” The Seminole, however, did not leave peacefully and resisted removal, resulting in the Second Seminole War, which lasted from 1835 to 1842. Eventually, they were forced to move, except for just a few who escaped.

By 1837, the Jackson administration had removed 46,000 Native American people from their land east of the Mississippi River. It had secured treaties, which led to the removal of a slightly larger number.

Indian Removal Act:

U. S. Government, 21st Congress, 2nd Session

Chapter CXLVIII – An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories and for their removal west of the Mississippi River.

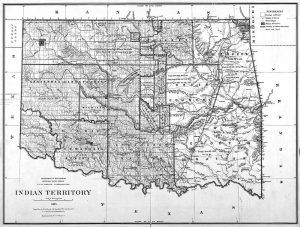

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That it shall and may be lawful for the President of the United States to cause so much of any territory belonging to the United States, west of the river Mississippi, not included in any state or organized territory, and to which the Indian title has been extinguished, as he may judge necessary, to be divided into a suitable number of districts, for the reception of such tribes Indians as may choose to exchange the lands where they now reside, and remove there; and to cause each of said districts to be so described by natural or artificial marks, as to be easily distinguished from every other.

Section 2 – And be it further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the President to exchange any or all of such districts, so to be laid off and described, with any tribe or nation within the limits of any of the states or territories, and with which the United States has existing treaties, for the whole or any part or portion of the territory claimed and occupied by such tribe or nation, within the bounds of any one or more of the states or territories, where the land claimed and occupied by the Indians, is owned by the United States, or the United States are bound to the state within which it lies to extinguish the Indian claim thereto.

Section 3 – And be it further enacted, That in the making of any such exchange or exchanges, it shall and may be lawful for the President solemnly to assure the tribe or nation with which the exchange is made, that the United States will forever secure and guaranty to them, and their heirs or successors, the country so exchanged with them; and if they prefer it, that the United States will cause a patent or grant to be made and executed to them for the same: Provided always, that such lands shall revert to the United States, if the Indians become extinct, or abandon the same.

Section 4 – And be it further enacted, That if, upon any of the lands now occupied by the Indians, and to be exchanged for, there should be such improvements as add value to the land claimed by any individual or individuals of such tribes or nations, it shall and may be lawful for the President to cause such value to be ascertained by appraisement or otherwise, and to cause such ascertained value to be paid to the person or persons rightfully claiming such improvements. And upon the payment of such valuation, the improvements so valued and paid for, shall pass to the United States, and possession shall not afterward be permitted to any of the same tribe.

Section 5 – And be it further enacted, That upon the making of any such exchange as is contemplated by this act, it shall and may be lawful for the President to cause such aid and assistance to be furnished to the emigrants as may be necessary and proper to enable them to remove to, and settle in, the country for which they may have exchanged; and also, to give them such aid and assistance as may be necessary for their support and subsistence for the first year after their removal.

Section 6 – And be it further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the President to cause such tribe or nation to be protected, at their new residence, against all interruption or disturbance from any other tribe or nation of Indians, or from any other person or persons whatever.

Section 7 – And be it further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the President to have the same superintendence and care over any tribe or nation in the country to which they may remove, as contemplated by this act, that he is now authorized to have over them at their present places of residence.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See: