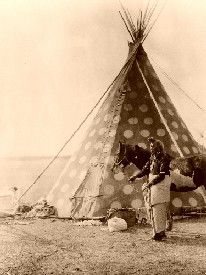

Blackfeet tribesman looks out over Glacier National Park, 1910. By Roland Reed.

The Blackfeet Confederacy is the name given to four Native American tribes in the Northwestern Plains, including the North Piegan, South Piegan, Blood, and the Siksika tribes. They initially occupied a large territory stretching from the North Saskatchewan River in Canada to the Missouri River in Montana. The four groups, sharing a common language and culture, had mutual defense treaties, gathered for ceremonial rituals, and freely intermarried.

Typical of the Plains Indians in many aspects of their culture, the Blackfeet, also known as Blackfoot in Canada, were nomadic hunter-gatherers who lived in teepees and subsisted primarily on buffalo and gathered vegetable foods.

Originally living in the northern Great Lakes Region, the Blackfeet was among the first tribes to move Westward. Thought to have been pushed out by their arch enemies, the Cree Indians, the Blackfeet began to roam the northern plains from Saskatchewan to the Rocky Mountains.

Oral tradition indicates that buffalo were first hunted in drives, and deer and smaller game were caught with snares. Although fish were abundant, they were eaten only when no other meat source was available.

The Blackfeet separated into bands near wooded areas of approximately 10 to 20 lodges during the winter, each encompassing somewhere between 100 and 200 people. Each band, led by a Chief, was large enough to defend against attacks but small enough to be mobile should provisions run short. The size also provided for buffalo hunts in the timbered regions where buffalo often wintered, sheltered from the storms, making them easy prey. Bands were defined by residence rather than kinship, and members could join other bands whenever they liked. Leaders of each band were an informal process, defined by wealth, war success, and ceremonial experiences.

When the buffalo moved out onto the grasslands in the spring, the Blackfeet followed after all trace of the winter had ended. The Blackfeet lived in large tribal camps during the summer, hunting buffalo and engaging in ceremonial rituals. In mid-summer, the people grouped for a major tribal ceremony, the Sun Dance. The assembly provided ceremonial rituals, social purposes, and warrior societies based on brave acts and deeds. Large buffalo hunts provided food and offerings for the ceremonies. After the Sun Dance assembly, the Blackfeet separated again to follow the buffalo.

The Blackfeet first saw horses in 1730, when the Shoshone tribe attacked them on horseback. For this reason, the Blackfeet were pleased when Europeans began to arrive, allowing them to gain horses themselves. However, their sentiments changed quickly as smallpox epidemics ravaged their population in the mid-1800s. Though they continued to trade buffalo hides, horses, and guns with the encroaching settlers, they primarily obtained their horses through trade with the Flathead, Kutenai, and Nez Perce tribes.

On January 23, 1870, one of the worst slaughters of Indians by American troops occurred, known as the Marias Massacre. While the U.S. Cavalry was looking for a band of hostile Blackfeet Indians led by Mountain Chief, they stumbled instead onto a peaceable band of Piegan Indians led by Chief Heavy Runner.

The cavalrymen spread out in an ambush position along the snowy bluffs overlooking the Marias River in the early morning hours. The encampment was unprotected as most of the men were out hunting, and before the command to fire was made, Chief Heavy Runner emerged from his lodge waving a safe-conduct paper. When an Army scout named Joe Kipp shouted that this was the wrong camp, he was threatened with silence. Another scout, Joe Cobell, then fired the first shot, killing Heavy Runner, and the massacre ensued.

When the carnage was over, 173 lay dead – primarily women, children, and the elderly. One hundred forty others were captured and later turned loose without horses, adequate food, and clothing.

As the refugees made their way to Fort Benton, Montana, some ninety miles away, many of them froze to death. In the meantime, Mountain Chief and his people had escaped across the border into Canada.

The Blackfeet maintained their traditions and culture until the white settlers made the buffalo almost extinct. In 1877, the Canadian Blackfeet felt compelled to sign a treaty that placed them on a reservation in southern Alberta. With the buffalo nearly extinct in Montana, many Blackfeet starved and were forced to depend upon the Indian Agency for food.

During the early 1800s, the Blackfeet had an estimated population of approximately 20,000. However, the diseases brought on by the white settlers, including smallpox and measles, along with starvation and war, reduced their number to less than 5,000 by the turn of the century.

In the face of these adversities, the Blackfeet have not lost their culture or language. Today, there are approximately 25,000 Blackfeet members. The Piegan Blackfeet are located on the Blackfeet Nation in northwestern Montana near Browning. The other three tribes, known as the Blackfoot, are primarily located in Alberta, Canada.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2024.

Contact Information:

Blackfeet Nation

P.O. Box 850

Browning, Montana 59417

406-338-7521/7522

Also See: