Located in Jefferson County, about 32 miles northeast of Natchez, Mississippi, Rodney was once such an important city that it nearly became Mississippi’s capital. Today, it is a ghost town with only a handful of area residents.

Long before a settlement was ever formed here, the location was a popular Mississippi River crossing for many Native Americans. It was also an early crossing place for travelers along the El Camino Real, the old Spanish “Royal Road.” Today, the old townsite isn’t on the Mississippi River anymore but about two miles inland.

Though Great Britain controlled the area as a result of the French and Indian War, it was first settled by the French in January 1763 and called Petit Gulf to distinguish it from the larger port of Grand Gulf.

In 1774, General Phineus Lyman from New England led an expedition through the area to organize a settlement on the Big Black River. Captain Matthew Phelps, a member of the expedition, described the area — Firm rock lies on the east side of the Mississippi River for about a mile. The land near the river is high, broken, and rich, and several plantations have been established.

The Spanish took control of West Florida from the British in 1781. Spain would hold the site until 1791, when a Spanish land grant deeded the site to Thomas Calvit, a prominent territorial Mississippi landholder. As settlements along the Mississippi River grew, so did the importance of the port of Petit Gulf. In 1814, the name of the town was changed to honor Judge Thomas Rodney, the territorial magistrate who presided at the Aaron Burr hearing.

One of the area’s earliest and most influential settlers was Dr. Rush Nutt, a physician, planter, scientist, and author of a multi-volume diary of travels on the Natchez Trace. A native of Virginia, Nutt grew up to earn a medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania. After graduating, he went on horseback to tour the “Southwest” in 1905. Settling in Petit Gulf, he married, set up a medical practice, and bought a large plantation. Calling his plantation Laurel Hill, he built a large mansion in about 1815.

The two-story frame structure, designed along simple lines with overhanging eaves protecting double galleries, was located about a mile southwest of Rodney. Becoming a planter, Dr. Nutt began experiments to develop a better cotton strain by crossing Mexican cotton with a local variety. Easy to pick and immune from rot, the successful strain became known as Petit Gulf or Nutt cotton and soon spread across the South and overseas. Nutt also improved the Whitney Cotton Gin and was the first in Mississippi to use a steam engine to drive the cotton gins.

He also encouraged his neighbors to use field peas as fertilizer, plow under cotton and corn stalks rather than burning them, and popularize contour plowing to prevent hillside erosion. In addition to his agricultural success, he was active in the civic affairs of early Mississippi and the town of Rodney. He was one of three founders of the nearby Oakland College. His son, Haller Nutt, shared his enthusiasm. Haller would later build the famous unfinished mansion of Longwood in Natchez, Mississippi. Dr. Nutt died in 1837 and is thought to be buried in the overgrown family cemetery near the old Laurel Hill Plantation House. The mansion was a private home until it burned down in 1982, leaving only the brick foundation and chimney behind.

When Mississippi was admitted as a state in 1817, Petit Gulf very nearly became the state’s first capitol, missing out to old Washington, near Natchez, by only three votes. In 1818, the Mississippi Legislature granted a charter of incorporation to the Presbyterian Church. In the beginning, the congregation would meet wherever they could, including at a local barroom.

A sketch of Rodney, in 1828, by French naturalist and painter Charles Lesueur revealed about 20 buildings leading from the river to the prominent bluff behind the town. That same year, the Town of Rodney was incorporated. By 1830, as river transportation continued to increase, Rodney had grown to a population of about 200, plus numerous area residents in the outlying area. It then sported 20 stores, a church, a newspaper, and the state’s first opera house. That same year, nearby Oakland College was established by Dr. Jeremiah Chamberlain. The Presbyterians also began to build their church in Rodney, which still stands today and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The two-story red brick building was dedicated on January 1, 1832. The dedication sermon was preached by Reverend Dr. Jerimiah Chamberlain, founder and president of Oakland College (now Alcorn University). The two-story red brick church was constructed in a Federal architectural style, with stepped parapets on the gable ends. The church bell was said to have been partially cast with 1,000 Silver dollars donated by church members. Before long, the city was known for its county fairs, a jockey club, a lecture hall, theatre groups, and its own quality schools. On several occasions, traveling actors and musicians on the passing steamboats entertained Rodney residents at the Masonic Hall.

Rodney gained its first newspaper, called The Southern Telegraph, in 1834. The four-page weekly was printed every Tuesday. Over the years, the newspaper changed editors and names, becoming the Rodney Standard and the Rodney Telegraph. One editor, Thomas Palmer, strongly opposed duels and whiskey and often editorialized on these topics. Another editor — Thomas Brown — was an unyielding Whig and strongly promoted the Whig political position. Though it changed hands several times, it kept the same headline motto: “He that will not reason is a bigot; he that cannot is a fool; and he that dares not is a slave.”

In the late 1830s, General Zachary Taylor, on a visit to Rodney, was so taken by the small town, its rich land, and the opportunity to profit from a cotton plantation that he decided to purchase land there. In late 1841, he sold his Louisiana and other Mississippi properties, and in early 1842, purchased the 1,923-acre Cypress Grove Plantation just a few miles south of Rodney, which he renamed the Buena Vista Plantation. The plantation, along with its 81 slaves, cost Taylor $60,000 in cash, the bulk of which represented the proceeds from selling his cotton crops and $35,000 in notes. Though the land lay in one of the wealthiest cotton-producing regions in the South, it would take several years to become profitable due to the mortgage debt. One visitor described the plantation house as an unpretentious wooden building with an extensive library and a colonnaded veranda. Taylor’s daughter, Sarah, eloped with Lieutenant Jefferson Davis during this time, much to her father’s dismay.

Due to his military duties, he seldom lived at the plantation, which an overseer ran. In 1846, he was off to fight in the Mexican-American War and returned a hero. He then retired to Buena Vista but was soon nominated for President. After winning the election, he left for the last time in January 1849, never to return. While in office, he became ill and died on July 9, 1850. Afterward, the Buena Vista Plantation, which was appraised at $20,000 and its 131 slaves at $56,650, was sold. The plantation house and outbuildings were destroyed in the Great Flood of 1927.

In 1843, Rodney was to suffer through a severe epidemic of yellow fever. It was so devastating that the outbreak was reported in national newspapers. The Philadelphia Inquirer and National Gazette reported on October 26, 1843:

“The Fever at Rodney – The last New Orleans papers say that at Rodney, Miss., the yellow fever continued to rage in its most fatal form. All the physicians, without exception, have been taken down with the disease. The death of Dr. J. H. Savage is reported, and Dr. Hulser, Dr. Pickett, Dr. Williams, Dr. Todd, and Dr. Andrews were all down sick.”

More locally, The Mississippi Free Trader and Natchez Gazette reported on October 7, 1843:

“Rodney, Miss – This village, about 40 miles above Natchez, has been visited by the yellow fever. Several deaths and a still greater number of well-marked cases have occurred – in consequence of which, we are informed by a Natchez physician and another Natchez gentleman who visited Rodney two days ago the village is almost depopulated. Even the only Apothecary’s shop in the place is closed, as are all the stores. Of course, there will be no need of quarantining against a village having no business and no inhabitants.”

Four years later, in 1847, the town was again visited by yellow fever, but this time, the duration was much briefer and far less destructive.

By the 1850s, Rodney had become the busiest port on the Mississippi River between New Orleans, Louisiana, and St. Louis, Missouri. Many of the major steamboats of the era made Rodney one of their chief ports of call. By this time, it had grown to nearly 1,000 area residents and boasted 35 stores, two banks, two newspapers, a large hotel, complete with a ballroom, and several churches and schools. In the next decade, it grew even faster, quadrupling its size to 4,000 residents by 1860. Its main business streets, Commerce and Magnolia, were lined with businesses, including banks, wagon makers, tinsmiths, barbers, doctors, dentists, general mercantile stores, hotels, saloons, and pastry shops. Mississippi Lodge #56 of the Free and Accepted Masons was located in Rodney from the 1850s until the 1920s.

The second church built in Rodney was the Mt. Zion No. 1 Baptist Church in 1850. Also known as the First Baptist Church, it is a one-and-a-half-story gable-front frame structure built in a transitional Greek-Gothic Revival architectural style. It features a pointed-arch entrance door with archivolt trim and is topped by a polygonal belfry with a domed cap. Before 2011, it had been restored and was in very good condition, with its interior paneling, pews, and preacher’s podium intact, and even a basket for visitor contributions. However, the April and May flooding of the Mississippi River took its toll on the building and many others in little Rodney. Its front doors stand open today, displaying fallen paneling, scattered pews, and debris throughout this once-important community building.

Like so many other southern towns, especially those along the Mississippi River, Rodney got its taste of Civil War action. In June 1863, 40 Union cavalry troops were disembarked in Rodney to launch a surprise raid to the east on the Confederate- controlled Mobile and Ohio Railroad. The Confederates won the engagement, capturing the Union troops, which sought to take the Mobile and Ohio Railroad.

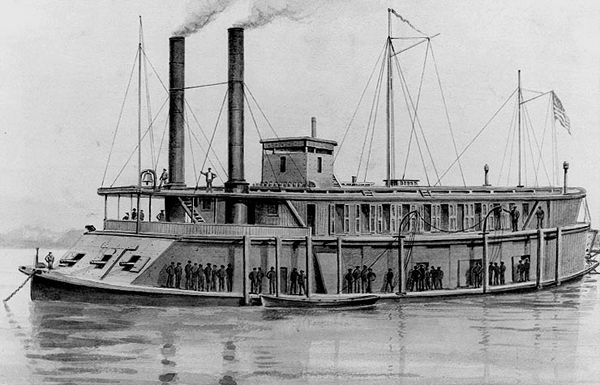

After the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, the Confederacy was cut in two. For the next two years, Union warships patrolled the Mississippi River to shut down all Confederate river traffic. The “tinclad” gunboat USS Rattler was stationed at Rodney. Though the Navy Admiral, David Porter, had left strict orders that no one was to leave the ship, the crew was restless. When the Reverend Baker, a northern sympathizer who was to preach at the Presbyterian Church, invited Captain Walter Fentress and his men to attend services on September 13, 1863, his invitation was accepted. That Sunday morning, the captain, a lieutenant, and some 18 soldiers arrived at the church, dressed in their best uniforms, and quietly seated themselves in the congregation. None were armed except Second Assistant Engineer A. M. Smith, who carried a hidden revolver. The sailors’ need for release from the boredom on the ship would prove unwise. Just as the second hymn began, a Confederate Calvary commander — Lieutenant Allen, walked up to the Reverend Baker, apologized for the interruption, and announced to the congregation that the church was surrounded by rebels and demanded the surrender of the Union sailors. When Engineer A.M. Smith drew his pistol and fired a shot through Lieutenant Allen’s hat, all hell broke out as the congregation dove beneath the pews. At the sound of the shot, the Confederate Cavalry surrounding the building fired through the windows, striking the ceiling or opposite wall. Confederate Lieutenant Allen then shot his revolver once into the ceiling, shouting for all to ceasefire. In the end, 17 Federal troops were captured by the Confederates, including the lieutenant and captain.

When word of the prisoners reached the Rattler, the gunboat bombarded the town and the church, which, at that time, was only about 300 yards from the Mississippi River. However, when the Confederate commander, Lieutenant Allen, sent word that if the shelling did not stop, all prisoners would be hanged, the Union ceased the shelling, but not before the church and four homes were hit. One of the cannonballs was embedded in the front of the church. By 1:30 p.m., the initial excitement had passed, and Rattler again lay at anchor but now in deep water. Afterward, the Rattler’s crew became the nation’s laughingstock, for it was the first time in history a small squad of cavalry captured the crew of an ironclad gunboat. After this attack, citizens of Rodney formed Company D. 22nd Mississippi infantry to fight against the Union army, and the Union sympathizing Reverend Baker soon left the area. Some months later, Captain Fentress and his men were exchanged for captured Rebel soldiers and resumed their Navy service at other posts.

In September 1864, Union troops were sent from Vicksburg to destroy a reported Confederate troop concentration at Rodney. Landing here, the Union infantry regiment plundered almost every house in town. Later that same year, the USS Rattler was hit by a heavy gale near Grand Gulf, Mississippi, on December 30, driving her ashore and causing her to strike a snag and sink. Though her crew survived, the gunboat was a total loss. After being abandoned by the U.S. Navy, she was burned by the Confederates.

Though Rodney and the surrounding area had been spared any great battles, the Civil War left its mark, as the land was stripped of food, livestock, and slaves by Union troops. Reconstruction further stripped away the prosperity of Rodney, as well as much of the South. The Civil War would spell the beginning of the end for this once-thriving port city.

Some, however, retained hope for the future, and in 1868, the Catholics built the Sacred Heart Church, an outstanding example of Carpenter Gothic architecture, with its board and batten siding, heavy label moldings, and wooden pinnacles. The church no longer stands in Rodney today, as it was moved to Grand Gulf Military Park in 1884.

Just a year after the Catholic church was built in Rodney, the town was almost entirely consumed by a fire, but, obviously, the Sacred Heart Church was spared. One witness of the fire, an officer aboard the steamer Richmond, described the blaze:

“Wednesday night, shortly after we left Vicksburg, a bright light was observed in the southern horizon. All manner of speculation was rife on board concerning the cause, and as the light grew nearer and nearer, the interest grew in proportion. At last, after several hours of eager watching, we bore in sight of the beautiful Town of Rodney, and lo, we beheld it the object of the wrath of the fire king. The whole village was wrapped in a mantle of flames and as at two o’clock in the morning our boat glided swiftly down along the other shore, the scene was grand beyond description, lit up as it was by the lurid lights from burning buildings, mingled with the moon’s pale beams.”

In the meantime, a greater “disaster” was forthcoming for Rodney. A large sand bar had formed in the nearby Mississippi River, causing the grand waterway to alter its course in about 1870. With the river now two miles west of Rodney, the town obviously lost its port. With many of its buildings destroyed by the fire of 1869 and its river commerce gone, many people left the area. Rodney’s population further declined when it was bypassed by the Natchez, Jackson & Columbus Railroad that reached nearby Fayette, Mississippi. With its citizens poor, it was too late for Rodney.

In 1923, the last full-time pastor of the Presbyterian Church resigned, leaving behind a congregation of just 16 people, although church services probably continued intermittently for several years. In 1966, the church was conveyed to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Two years later, Mississippi appropriated funds for the restoration. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. It continues to stand in Rodney today, surrounded by many historic signs. The church’s front facade displays a cannonball above the upper middle window. Though this is not the original cannonball that hit the building in 1863, it is an authentic ball of the period, placed during restoration at the spot where the church was initially hit. Today, the exterior of one of the state’s oldest churches is deteriorating again due to flooding and lack of funding.

Though several people still lived in Rodney in 1930, its life as an “official” town ended permanently with an executive proclamation by Governor Theodore Bilbo.

By 1933, the population of Rodney had diminished to less than 100; by 1957, only seven congregation members remained at the Sacred Heart Catholic Church. In February 1969, the Catholic Diocese of Natchez-Jackson conveyed the property to the Rodney Foundation, Inc. However, by 1982, the foundation found it could not restore and maintain the building and donated it to the state of Mississippi. A year later, the church was moved to the Grand Gulf Military Park, where it stands today. The central tower no longer retains its original pinnacles and wooden crenellation but was completely restored. The interior is finished with simple plaster walls and a wooden ceiling and floor. It is open today for visitors of the park and continues to be a non-denominational chapel by religious and other groups approved by the park. In 1894, the church was the setting for the christening of the future Most Reverend Bishop Charles P. Greco, Bishop of the Diocese of Alexandria (Louisiana). Bishop Greco was the first Mississippian to become a Roman Catholic Bishop.

The Mt. Zion No. 1 Baptist Church, also called the First Baptist Church in Rodney, Mississippi, was built in 1850.

The last church to be actively used was the 1850 Baptist Church. Though still standing, its interior was virtually destroyed by the floods in 2011. The small town of Rodney still supports just a handful of citizens and several of its original buildings. The Rodney Center Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. Some homes have been maintained or restored and continue to be utilized as homes today. However, there are no remaining businesses in this small town. The Opera House, town hall, and other major commercial buildings have long disappeared. However, a two-story red brick commercial building and the old Alston Grocery Store continue to stand. This business, operated by the Alston family since 1915, was probably the last to close. More buildings remain in various stages of decay or have completely fallen to the ground and are overgrown with trees and brush.

Today, there is only one serviceable road in and out of Rodney. From Alcorn, highway M-558 dead-ends at the once-bustling river port town. The final three miles are dirt and gravel.

The Rodney Town Cemetery is on the wooded bluff behind the Presbyterian church. Abandoned and overgrown today, it contains the remains of locals and the graves of river travelers and folks from Saint Joseph, Louisiana, across the river from Rodney. Many of the graves are enclosed in rusting, ornate wrought-iron fences. The traces of Confederate Civil War trenches overlooking the old riverbed can also be found here. These defenses once gave a commanding view of the area and the river.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Zachary Taylor – Distinguished General & President

Grand Gulf – A Bustling Port Along the River

Mississippi River and the Expansion of America