A short distance up Bayou Pierre from its mouth once stood the small settlement of Bruinsburg and its landing on the Mississippi River. The settlement was established by Peter Bryan Bruin, who arrived, along with several other families in 1788. An Irishman, Bruin immigrated to the United States in 1756 and began working as a merchant in the Virginia Colony. In 1775, he became a lieutenant of Virginia provincials and would fight for the United States in the American Revolution. When the fighting was over, he returned to Virginia to a poor economy and his father was forced to sell hundreds of acres of their land to settle debts. His father, Bryan Bruin, then petitioned Spanish Minister Don Diego María de Gardoqui, who then governed what would become Mississippi, for land grants for himself, his son, and other families from Virginia.

Peter Bryan Bruin’s land grant of 1,200 acres was very generous because he brought 12 families with him. Situated at the northernmost point of the Natchez District near the mouth of Bayou Pierre. Bruin and several other people established homes here in 1788. In exchange for the land grant, Bruin was required to pay the survey and recording fees and make improvements on the land including a cabin, planting crops, and clearing and fencing the Mississippi River frontage. Within three years, he owned the land outright, and soon the region was filled with tobacco, indigo, corn and cotton fields, fruit orchards, and large gardens growing all manner of vegetables.

He became a leading man in the Natchez District and was made an alcalde by the Spanish government. Later, when the territory was organized as an American possession, he was appointed one of the three territorial judges, entrusted with the making of laws and the administration of justice. In 1807, none other than Aaron Burr, who was wanted for crimes of treason, stopped at Judge Bruins for a visit. He was pursued by a detachment of militia, but when they arrived, Burr had fled downriver three miles. Bruin continued to hold the office of the judge until he resigned in 1809. He continued to live in Bruinsburg and also expanded across the Mississippi River, where he had another plantation in Concordia Parish, Louisiana. He died at Bruinsburg on January 27, 1827.

During the heydays of busy Mississippi River traffic, Bruinsburg became a lively port and cotton market and somewhere along the line, the future President Andrew Jackson set up a trading post here for a time. However, years later, the Civil War brought an end to Mississippi River commerce and ultimately, to Bruinsburg, itself.

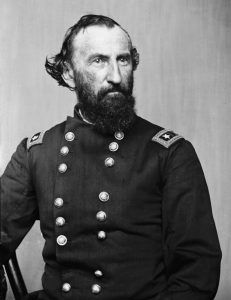

In April 1863, Bruinsburg would become famous for another historical event when Union Major General Ulysses S. Grant utilized it’s landing to dispatch some 40,000 Union soldiers in his Campaign Against Vicksburg. With river traffic all but non-existent, the landing was nearly deserted. Only the nearby Windsor Plantation, testified to the area’s past prosperity.

On April 29, 1863, General Ulysses S. Grant’s objective was to force a crossing of the Mississippi River from Louisiana at Grand Gulf, Mississippi, and then move on to Vicksburg from the south. For five hours, a Union fleet of seven ironclads bombarded the Grand Gulf defenses in an attempt to silence the Confederate guns and prepare the way for a landing. The fleet, however, sustained heavy damage and failed to achieve its objective, resulting in Union Rear Admiral David D. Porter declaring: “Grand Gulf is the strongest place on the Mississippi.”

Though the Grand Gulf assault was disappointing, it did not end Grant’s ambitions to cross the river, and he began to move his troops south. While Admiral Porter provided cover for the movement of the transport vessels, Grant was busy with intelligence-gathering operations.

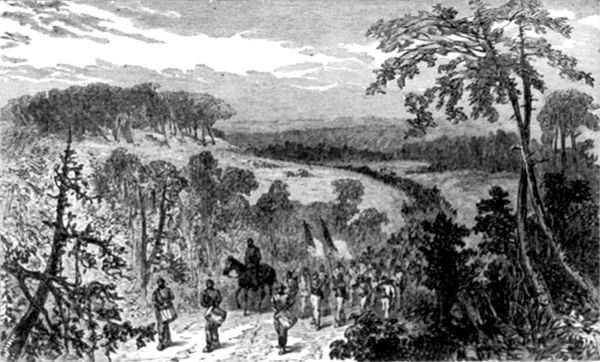

He dispatched reconnaissance parties across the river seeking information on possible landing sites and roads inland in the vicinity of Rodney, Mississippi. One of these parties returned with a fugitive slave from Louisiana, who would guide Grant and his troops on their path to Port Gibson. On April 30th the landing was made unopposed and, as the men came ashore, a band aboard the U.S.S. Benton struck up “The Red, White, and Blue.”

This first group was followed by the remainder of the XIII Union Army Corps and portions of the XVII Corps and by late afternoon of April 30, 17,000 soldiers were ashore and the march inland began. This landing was the largest amphibious operation in American military history until the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II. Elements of the Union army pushed inland and took possession of the bluffs, thereby securing the landing area. Thousands more followed the next day.

Moving away from the landing area at Bruinsburg, the Federal soldiers rested in the shade of the trees on Windsor Plantation. Late that afternoon the decision was made to push on that night by a forced march in hopes of surprising the Confederates and preventing them from destroying the bridges over Bayou Pierre. The Union columns resumed the advance at 5:30 p.m., but, instead of taking the Bruinsburg Road — the most direct road from the landing area to Port Gibson — Grant’s columns swung onto the Rodney Road, passing Bethel Church and marching through the night.

Additional troops arrived at Bruinsburg Crossing the next day, following their comrades inland for the remaining battles of the campaign.

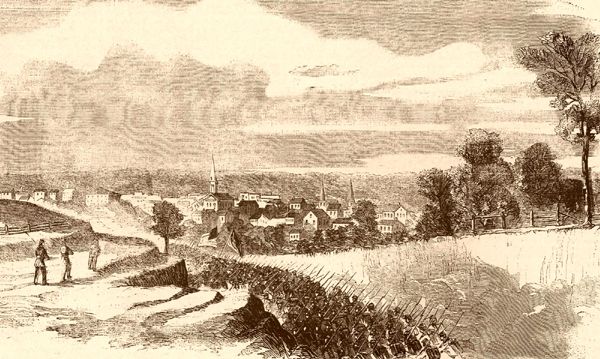

Battle of Port Gibson (May 1, 1863) – Once Union General John A. McClernand’s corps landed at Bruinsburg, their objective was to capture Grand Gulf, which was to be Grant’s base. From Grand Gulf, Port Gibson was the next target, as roads from there led to Vicksburg and Jackson. A road led directly from Bruinsburg to Port Gibson, and Bayou Pierre, a navigable stream, bisected the road. Once McClernand’s 14th Corps of 17,000 strong landed, the rebels abandoned Grand Gulf and moved toward Port Gibson. Hoping to capture the bridges over Bayou Pierre before the retreating Confederates destroyed them, McClernand ordered a forced march during the evening of April 30-May1.

In the meantime, Confederate General John C. Pemberton had been completely confused by Grant’s diversions and had widely dispersed his troops to defend Vicksburg. As a result, there were few Confederates present to contest Grant’s march inland from Bruinsburg.

On April 30, 1863, the Confederate brigades of Brigadier Generals Martin E. Green and Edward Tracy marched south along the Bruinsburg Road to contest the Union invasion of Mississippi and block both the Rodney and Bruinsburg Roads west of Port Gibson. At the point of deployment, an interval of 2,000 yards separated the roads. The brigades of Tracy, on the right, and Green, on the left, were separated by a deep cane-choked ravine which prevented one flank from reinforcing the other flank. To do so, the Confederates had to march back to the road junction. The “Y” intersection of the roads was thus the lateral avenue of movement for the Confederates.

Shortly after midnight, the crash of musketry shattered the stillness as the Federals stumbled upon Confederate outposts near the A. K. Shaifer house. Union troops immediately deployed for battle, and their artillery, which soon arrived, roared into action. A spirited skirmish ensued which lasted until 3:00 a.m, with the Confederates holding their ground. For the next several hours an uneasy calm settled over the woods and scattered fields as soldiers of both armies rested on their arms. Throughout the night the Federals gathered their forces in hand and both sides prepared for the battle which they knew would come with the rising sun.

At dawn, Union troops began to move in force along the Rodney Road toward Magnolia Church. One division was sent along a connecting plantation road toward the Bruinsburg Road and the Confederate right flank. With skirmishers well ahead, the Federals began a slow and deliberate advance around 5:30 a.m. The Confederates contested the thrust and the battle began in earnest.

Rodney Road, Mississippi

Most of the Union forces moved along the Rodney Road toward Magnolia Church and the Confederate line held by Brigadier General Martin E. Green’s Brigade. Heavily outnumbered and hard-pressed, the Confederates gave way shortly after 10:00 a.m. The men in gray fell back a mile and a half. Here, the soldiers of Brigadier General William E. Baldwin’s and Colonel Francis M. Cockrell’s brigades, recent arrivals on the field, established a new line between the White and Irwin branches of Willow Creek. Full of fight, these men re-established the Confederate left flank.

The morning hours witnessed Green’s Brigade driven from its position by the principle Federal attack. Brigadier General Edward D. Tracy’s Alabama Brigade, astride the Bruinsburg Road, also experienced hard fighting. Although Tracy was killed early in the action, his brigade managed to hold its tenuous line.

It was clear, however, that unless the Confederates received heavy reinforcements, they would lose the day. Brigadier General John S. Bowen, Confederate commander on the field, wired his superiors: “We have been engaged in a furious battle ever since daylight; losses very heavy. The men act nobly, but the odds are overpowering.” Early afternoon found the Alabamans slowly giving ground. Green’s weary soldiers, having been regrouped, arrived to bolster the line on the Bruinsburg Road.

Even so, by late in the afternoon, the Federals had advanced all along the line in superior numbers. As Union pressure built, Cockrell’s Missourians unleashed a vicious counterattack near the Rodney Road and began to roll up the blue line. The 6th Missouri also counterattacked, hitting the Federals near the Bruinsburg Road. All this was to no avail, for the odds against them were too great. The Confederates were checked and driven back, the day lost. At 5:30 p.m., the battle-weary Confederates began to retire from the hard-fought field.

The battle of Port Gibson cost Grant 131 killed, 719 wounded, and 25 missing out of 23,000 men engaged. This victory not only secured his position on Mississippi soil but enabled him to launch his campaign deeper into the interior of the state. Union victory at Port Gibson forced the Confederate evacuation of Grand Gulf and would ultimately result in the fall of Vicksburg.

After the battle, Brigadier General John A. Logan’s troops entered the town of Port Gibson, Mississippi.

The Confederates suffered 60 killed, 340 wounded, and 387 missing out of 8,000 men engaged. In addition, 4 guns of the Botetourt (Virginia) Artillery were lost. The action at Port Gibson underscored the Confederate inability to defend the line of the Mississippi River and to respond to amphibious operations. Confederate soldiers from these operations are buried at Wintergreen Cemetery in Port Gibson.

Now firmly established below Vicksburg, Grant would continue to take north, taking Raymond on May 12th and the capitol of Jackson on May 14th. From there, the Union troops turned west again, winning the battles of Champion Hill on May 16th and the Battle of the Big Black River Bridge the next day. On May 18, 1863, the Siege of Vicksburg would begin, Lasting for nearly six weeks, the prolonged battle would become a major turning point in the Civil War giving control of the Mississippi River to the Union and foreshadowing the fall of the South.

Civil War Sites:

Bayou Pierre Presbyterian Church – Following the arrival of Presbyterian missionaries in 1801, Joseph Bullen and James Smylie organized the Bayou Pierre Church at this site in 1807. After part of the congregation formed the Bethel Church to the southwest in 1824, the remaining members moved to Port Gibson. A reconstruction of this crude log church stands on the site today.

During the Battle of Port Gibson, fought on May 1, 1863, the 20th Alabama Infantry was posted here, anchoring the right flank of Confederate Brigadier General Edward D. Tracy’s Brigade. The thin gray line ran southeastward for 1,000 yards, paralleling the Bruinsburg Road. Shortly after 8 a.m., the Confederate skirmishers began to fall back and the mainline opened fire.

It was at this time, recalled Sargeant Francis Obenchain of the Botetourt (Virginia) Artillery, that while speaking with General Tracy, “a ball struck him on back of the neck passing through. He fell with great force on his face and in falling cried `O Lord!’ He was dead when I stooped to him.” Edward Tracy was the first of several Confederate generals to die in defense of Vicksburg. Even so, the Confederates held their tenuous line all morning against heavy Federal pressure.

The Alabamans were reinforced in the afternoon by Martin E. Green’s brigade which extended the line eastward. The Confederates handled their weapons with grim determination and skill, but it was evident their line was slowly giving way. Late in the afternoon, the Federals managed to turn the Confederate flank at the overlook. Unable to stem the blue tide along both the Bruinsburg Road and the Rodney Road, the Confederates retired from the field.

Bethel Presbyterian Church – Bethel Presbyterian Church is one of the few remaining landmarks associated with the battle of Port Gibson. The original congregation of the Bethel Presbyterian Church organized in 1826 under the direction of Dr. Jeremiah Chamberlain. The building that still stands today, was built in the mid-1840s. During Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign to take Vicksburg, he landed his troops east of the Mississippi River just a few miles from here at Bruinsburg. His troops passed Bethel Church on April 30, 1863, moving to Port Gibson on the Rodney Road. After conquering Port Gibson, the troops moved onward to take Raymond and Jackson, before moving westward to Vicksburg.

Although the slave gallery has been removed and the original pointed steeple destroyed by a tornado in 1943, the church retains the classical symmetry of the Greek Revival style. Bethel Church is located one mile north of Canemount Plantation and two and a half miles south of Windsor Ruins on the Windsor Loop off of the Natchez Trace.

Bruinsburg Landing – After arriving at Bruinsburg Landing, the Union soldiers marched inland toward Port Gibson on a sunken stretch of road known as the Rodney Road. Of the old road, a Union soldier wrote, “The moon is shining above us and the road is romantic in the extreme. The artillery wagons rattle forward and the heavy tramp of many men gives a dull but impressive sound.” The Battle of Port Gibson took place along this route near the Shaifer House and Magnolia Church. Mississippi River Commerce virtually ceased during the Civil War, dealing a death blow to the small settlement of Bruinsburg. The economic collapse during and after the war finished it. By 1865, the town was “officially” extinct. In a 1938 tour book, Bruinsburg Landing was described as affording one of the best views of the Bayou Pierre and that there were a few inhabitants living in a primitive logging camp. Today, there is nothing left of the former town, and the site is located on private property. Not too many years ago, highway 552 provided access to the Mississippi River at the mouth of Bayou Pierre, but, that access is also closed today.

Bruinsburg Road – On April 30, 1863, the Confederate brigades of Brigadier Generals Martin Green and Edward Tracy marched south along the Bruinsburg Road to contest the Union invasion of Mississippi. The next day, May 1, the brigades of Brigadier General William Baldwin and Colonel Francis Cockrell hastened out the Bruinsburg Road to reinforce the Confederate troops then heavily engaged with Grant’s forces. Late in the afternoon of May 1, Baldwin’s men would retire from the field along the road into Port Gibson followed by the victorious Union soldiers. Confederate troops were deployed to block both the Rodney and Bruinsburg Roads west of Port Gibson. At the point of deployment, an interval of 2,000 yards separated the roads. The brigades of Tracy, on the right, and Green, on the left, were separated by a deep cane-choked ravine which prevented one flank from reinforcing the other flank. To do so, the Confederates had to march back to the road junction. The “Y” intersection of the roads was thus the lateral avenue of movement for the Confederates.

Portions of the old Bruinsburg Road are part of MS Highway 552 today.

Magnolia Church – On April 30, 1863, Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green deployed his brigade along the Rodney Road just east of Magnolia Church. His thin line of four small regiments was strengthened by four guns of the Pettus Flying Artillery. At 5:30 a.m., May 1st, the Federals advanced in overwhelming numbers along the Rodney Road toward Green’s position. It was not long before his line was hard-pressed and the artillery unit supporting him out of ammunition. Green was reinforced shortly after 8 o’clock by two guns of the Botetourt (Virginia) Artillery and the 23d Alabama Infantry. Even so, he could not stem the Federal advance. At 10:00 a.m. the blue line surged forward, captured the guns of the Virginia battery, and drove the Confederates from their position.

As Green’s men scrambled to the rear, the brigades of Brig. Gen. William E. Baldwin and Col. Francis M. Cockrell arrived and established a new line between White and Irwin branches of Willow Creek. Here the battle was renewed at mid-afternoon. The Confederates fought tenaciously but were no match for the powerful Union battle lines which came on relentlessly. At 5:30 p.m. Bowen telegraphed his superiors in Jackson, “I am falling back across Bayou Pierre. The men did nobly, holding out the whole day against overwhelming odds.”

The church was situated about four miles southwest of Port Gibson on Rodney Road. Today, only its brick foundation and the cistern remain, but, a historic marker designates the site.

Rodney Road – Much of the Rodney Road has changed little since the days of the Civil War. Imagine soldiers marching down this road, tightly packed in columns of four, the stillness of the night broken by the sounds of their marching feet, clanking accouterments, and the rumbling of wagons and artillery pieces. Prior to the Battle of Port Gibson, it was a clear, moonlit night, and tension and fear were in the air, for these soldiers knew they were on enemy soil and that enemy was near, but where? As they marched along in the late-night hours many of the soldiers dozed. One bluecoat recalled the night march as being “romantic in the extreme.”

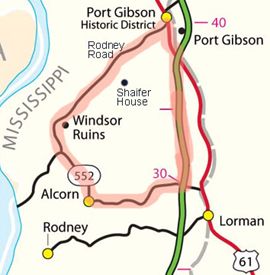

Today portions of the old Rodney Road form Mississippi Highway 552 and part of the Windsor Loop, a 32-mile driving/biking tour off the Natchez Trace, where many of the Civil War sites listed here can be seen. Other portions of the old Rodney Road remain virtually unimproved, looking much like they have for some 200 years.

Shaifer House – Built in the late 1820s by Abram Keller Shaifer, Sr. and his wife, Elizabeth Hannah Humphreys Shaifer. Abram was away from home, in service to the Confederate army, at the time of the Battle of Port Gibson on May 1, 1863. The opening shots of the skirmish occurred here. Shortly after midnight the Federal vanguard forded Widows Creek and climbed the long grade to the Shaifer house. As they neared the house, a shot rang out. Union troops responded with a volley of musketry. The battle of Port Gibson had begun. In the darkness the battle increased in fury; then suddenly, about 3 a.m., the guns fell silent. The fighting resumed about 5:30 a.m. as the Federals advanced toward Magnolia Church. One division was sent along a connecting plantation road toward the Bruinsburg Road. Throughout the morning hours, the battle raged near the Shaifer house. Federal troops continued to pass by the house all afternoon and bivouacked in the yard that night. When the battle was over, the house was used as a surgical hospital for wounded soldiers.

The Shaifer family donated the house and grounds to the state in the late 1970s, and the property was transferred to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in 1999. It was restored in 2006.

Windsor Ruins Loop – This 32-mile long loop off the Natchez Trace, passing through Alcorn and Port Gibson, Mississippi, provides a number of interesting stops. The loop is comprised of 20 miles along Mississippi Highway 552/Rodney Road, seven miles along the Natchez Trace Parkway from milepost 30 to 37 and five miles through the town of Port Gibson and back to the Trace. The Driving/biking route provides views of Alcorn University, the oldest public historically black land-grant institution in the United States and the second oldest state-supported institution of higher learning in Mississippi; Canemount Plantation, Bethel Church and more. A side trip off this loop will take you to the ghost town of Rodney, which at one time was so important it almost became the capital of Mississippi.

Windsor Ruins – Sitting like a lonely “Stonehenge” about ten miles southwest of Port Gibson, near the Mississippi River, Windsor Ruins has an interesting history, and, perhaps, a few legends as well. Legend says that from a roof observatory, Mark Twain watched the Mississippi River in the distance. Leading up to the Battle of Port Gibson in the spring of 1863, Confederate troops used the roof observatory as a lookout as General Ulysses S. Grant’s army crossed the Mississippi River. After the battle, the mansion was used as a Union hospital and observation post, thus sparing it from being burned by Union troops. However, years later it burned to the ground, leaving behind only its 45-foot elaborate pillars.

Wintergreen Cemetery – Established in 1807, Wintergreen Cemetery is the final resting place for the majority of soldiers killed in the Battle of Port Gibson. Shortly after the conflict, the townspeople removed the Confederate dead from the battlefield and interred them here in Soldiers’ Row. Small footstones marked C.S.A. were placed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. These small footstones are still in place.

In 1985 an effort was initiated by Roger B. Hansen of Pascagoula, Mississippi, to identify the Confederates buried in Wintergreen. The year-long project resulted in the only documented listing of these Battle of Port Gibson dead. The list was used to acquire headstones from the Department of Veteran Affairs, and these were erected in 1986.

In 1985 an effort was initiated by Roger B. Hansen of Pascagoula, Mississippi, to identify the Confederates buried in Wintergreen. The year-long project resulted in the only documented listing of these Battle of Port Gibson dead. The list was used to acquire headstones from the Department of Veteran Affairs, and these were erected in 1986.

Confederate Generals Earl Van Dorn and Benjamin Grubb Humphreys are also interred in Wintergreen Cemetery, but not in Soldiers’ Row. Confederate Major General Earl Van Dorn was born near Port Gibson on September 17, 1820. Graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1842, Van Dorn saw service in the Indian campaigns, served with gallantry in the war with Mexico, and attained the rank of major in the 2d U.S. Cavalry before the outbreak of the Civil War.

Commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate service in June 1861, and a major general three months later, he commanded the Army of the West in the Battle of Pea Ridge. Although defeated, he remained in high esteem, and later commanded the Army of Mississippi at the Battle of Corinth. Again defeated, he was removed as army commander and placed in charge of Confederate cavalry operating in Mississippi. In this capacity he enjoyed much success, with the crowning achievement of his military career coming in December 1862 when his command destroyed General Grant’s Union supply base at Holly Springs, Mississippi, temporarily halting the Federal overland campaign against Vicksburg.

On May 7, 1863, Earl Van Dorn was shot and killed in Spring Hill, Tennessee by Dr. James B. Peters for what the doctor claimed was the violation of the “sanctity of his home.”

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2021.

Also See:

Natchez Trace – Traveled For Thousands of Years

Rodney, Mississippi – From Prominence to Ghost Town

The Vicksburg Campaign — Vicksburg is Key!

Windsor Ruins – A Silent Sentinel to the Magnificent South