Primary Cowtowns:

Secondary Cowtowns:

Cattle Trails:

The Chisholm Trail – Herding the Cattle

The Shawnee Trail – Driving Longhorns to Missouri

More:

Driving Cattle

During the Civil War, Texas cattle were no longer allowed to be shipped northward, effectively cutting off the income and much of the economy of the Confederate state of Texas. When the war was finally over, this policy had led to a large abundance of Texas cattle — some five million head — roaming the ranches of the Lone Star State. With no railroads to ship them to market, the cattle were worth only $3 to $4 ahead. In the meantime, there was a pent-up demand for beef in the northern and eastern states, where the going rate was ten times that amount.

Realizing the immense profits, Texas cattlemen began searching for the nearest railheads. However, this would not be as easy as it might seem. For several years, Missouri and Kansas farmers feared the Texas Longhorns coming through or entering their states due to a cattle disease called “Texas Fever.” The longhorn cattle appeared to be perfectly healthy, but Midwestern cattle allowed to mix with them or to use a pasture recently vacated by the longhorns sometimes became ill and often died. It was determined that ticks spread the disease to the local cattle, but the longhorns were immune.

In the spring of 1866, drovers wrangled an estimated 200,000 to 260,000 longhorns northward along the Shawnee Trail from Texas. While many were turned back or severely delayed due to Texas Fever, some drovers diverted their herds around the hostile settlements, getting their cattle to market and making large profits.

But the days of cattle blazing the Shawnee Trail were virtually over. In the first half of 1867, six states enacted laws against trailing, and Texas cattlemen knew something else would have to be done. At about this time, a young livestock dealer named Joseph G. McCoy conceived the idea of establishing a shipping depot for cattle at some point in the West and knew that the railroad companies were interested in expanding their freight operations. He soon selected Abilene, Kansas, and opened the Abilene Trail through Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Thus began the era of the long cattle drive and Kansas cowtowns.

As the developing railheads moved westward, so did the wild and wooly frontier towns, including Ellsworth, Caldwell, Wichita, and Dodge City. In Newton, Hunnewell, Great Bend, Hays, Brookville, Coffeyville, Salina, and Junction City, secondary cattle markets also succeeded briefly as cowtowns.

Meeting the demands of the many cowboys coming off the Chisholm Trail, dance halls and saloons, which almost always featured gambling, were fixtures in these Kansas cowtowns. Brothels and prostitution were other businesses that excelled, with a high percentage of men arriving and very few women accommodating them. The towns grew quickly, often levying taxes on the vices provided to the cowboys – liquor, gambling, and prostitution. They also quickly grew reputations described as “wicked, decadent, evil, and lawless.”

Between 1865 and 1885, hundreds of thousands of Texas Longhorns were driven to these shipping points. However, by the mid-1880s, several events ended the cattle drive era in Kansas. Most prominently was the railroad’s arrival into Texas, but also factoring in were quarantine laws and homesteaders that closed off much of the open range. But the cattle business in Kansas did not end. By 1890, the state ranked third in the nation in cattle production. As to the cowtowns themselves, most moved into a quieter existence, becoming peaceable agricultural communities.

Many famous Old West characters gained or bolstered their reputations in these cow towns, men such as Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Wild Bill Hickok, John Wesley Hardin, and dozens of others. Some of the most famous gunfights of the American West also occurred in these wild frontier towns, including the Dalton Gang Shoot-Out in Coffeyville, the Hyde Park Gunfight in Newton, and the Long Branch Saloon Shootout in Dodge City.

Kansas Cowtowns:

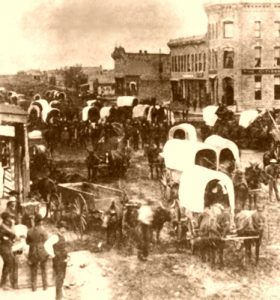

Vintage Abilene, Kansas

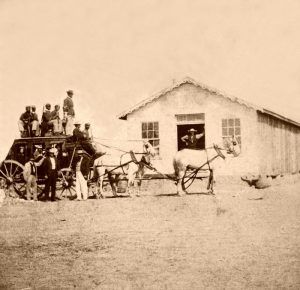

Abilene – Abilene already existed before it became a cowtown. In 1857, it was established as a stagecoach stop and was officially laid out in 1860. However, it retained a sleepy existence until a livestock dealer from Illinois named Joseph G. McCoy saw Abilene as the perfect place for a railhead to ship cattle in 1867. The city soon filled with not only cowboys but also gamblers, outlaws, and prostitutes. By 1870, it had become so lawless that Abilene hired its first marshal, Thomas Smith, whose first official act was to issue an order that no one would be allowed to carry firearms within the city limits without a permit. However, Smith was killed in the line of duty before the year ended. The following year, Wild Bill Hickok became the city’s marshal. Abilene reigned supreme as the Queen of Kansas cowtowns until new railheads in Newton, Wichita, and Ellsworth became the favored shipping points in 1872.

Baxter Springs – The first Kansas cowtown to develop was Baxter Springs, in the corner of southeast Kansas. In 1865, after the war was over, a town was laid out on 80 acres by Captain M. Mann and J. J. Barnes, and soon after that, Baxter Springs became an outlet for the Texas cattle trade. As Missouri became off-limits for Texas cattle due to quarantines, Baxter Springs welcomed them to Kansas. The community built stockyards with corrals capable of holding 20,000 cattle and provided rangeland with plenty of grass and water. Though the town took on all the appearances of prosperity, it also inherited a reputation as one of the wildest cowtowns in the West. Baxter Springs remained a cattle outlet through the 1870s as the herds were driven up the Old Shawnee Trail.

Brookville – When the Kansas Pacific Railroad arrived in 1870, the town served briefly as a cattle shipping area. It soon boasted 800 people, a bank, a newspaper, telegraph and express offices, a post office, and other businesses. Brookville is a virtual ghost town with just about 240 people.

Caldwell – Challenging Dodge City for the cattle market in the 1880s, Caldwell was known as the “Border Queen” for her location near the Oklahoma border. Situated along the Chisholm Trail, Caldwell catered to the many cowboys who passed by with their large cattle herds on their way to Abilene and Wichita even before the town became a shipping point itself. However, in 1879, the Santa Fe Railroad extended its line to Caldwell, and the town found itself in the middle of the cattle trade. It sprouted saloons, gambling dens, and brothels in no time, providing a place where the cowboys could go wild after months on the dusty and treacherous trail. Gunfights, showdowns, general hell-raising, and hangings soon became commonplace.

Coffeyville – As early as 1803, the present site of Coffeyville was occupied by the Black Dog band of Osage Indians who roamed this part of Kansas and northern Oklahoma, hunting buffalo. The site was first settled by white men in 1869 when Colonel James A. Coffey established an Indian Trading Post. News of the trading post spread quickly through the tribes living southward in Indian Territory, and the business thrived. Soon, several settlers came to the area, and the new town that formed around the trading post was called Coffeyville, which was in the Colonel’s honor.

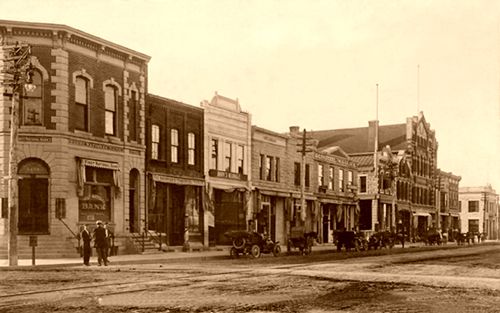

Dodge City – The wickedest and most well-known Kansas cowtown, Dodge City got its start before the cattle trade as a stop along the Santa Fe Trail and served as a civilian community near Fort Dodge. Later it developed into a buffalo-hunting town. In September 1872, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad arrived in Dodge City, initiating tremendous growth for many years. When quarantine laws closed Wichita to the cattle trade, Dodge City emerged as the “Queen of the Cowtowns.” From 1875 – 1885, more than 75,000 head of cattle were shipped annually. Many thousands more were driven through Dodge to stock northern ranges or to be shipped from other railheads.

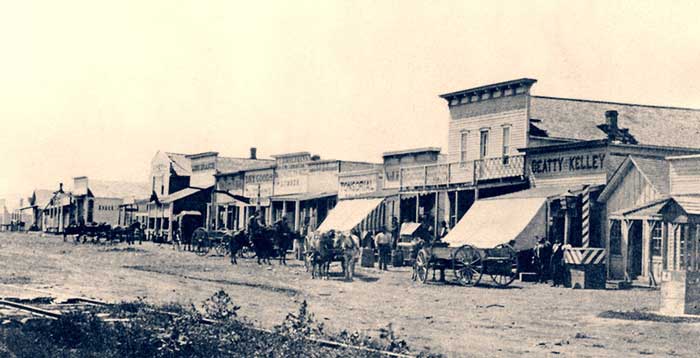

Dodge City, circa 1875

Ellis – Primarily a railroad town in its early days, Ellis was laid out by the Kansas Pacific Railroad in 1873, though a post office had already been established in 1870. The first business was a merchandise store started by Thomas Daily. The town became a secondary shipping point for cattle herds in 1875, and as such, took on many of the same characteristics typical of other Kansas cowtowns. By 1880, the shipping trade was over. Today, the primarily agricultural town is home to about 1,800 people.

Ellsworth – Long before Ellsworth began to dominate the cattle market, it was already a turbulent place. The Smoky Hills region had long been home to the Cheyenne and other Indian tribes who roamed the area killing buffalo. However, when the Santa Fe and Smoky Hill Trails came through, they began to raid wagon trains and stagecoaches, prompting the building of nearby Fort Ellsworth, which later changed its name to Fort Harker. When the railroad extended its line to Ellsworth, it quickly developed into a thriving cattle market, dominating other Kansas cowtowns from 1871 to 1875. With the flood of cowboys also came gamblers, outlaws, the inevitable “unruly” women, and a bad reputation.

Great Bend – Before it became a town, the site that would become Great Bend held only a trading post on the Santa Fe Trail, which ran right through Great Bend’s present-day Courthouse Square. The first settlers came to the area in about 1870, living in rough dugouts and sod houses. The following year, the town was officially formed, soon becoming a secondary market in the cattle trade, complete with shootouts, Texas cowboys, and saloons. Afterward, Great Bend settled down as a regional trade center. Today, the Barton County Seat is home to about 15,000 people.

Hays City – Hays started in 1867 as the southern branch of the Union Pacific Railroad worked its way west. Hays City was named after Fort Hays, which was founded in 1865. Like Junction City and Great Bend, Hays was never a significant cattle market but did receive some business due to its location on the railroad line and the ready market at Fort Hays. The combination of railroad workers, freighters, buffalo hunters, and soldiers, plus occasional cowboys, made it a very rough town for several years, at one time sporting 37 saloons and dance halls. Several colorful Old West characters lived in Hays, including the Custers and the 7th Cavalry, Wild Bill Hickok, and William F. Cody, who acquired his nickname of Buffalo Bill by furnishing buffalo to feed the railroad workers in Hays. Today, Hays has a population of over 20,000 and is the county seat of Ellis County.

Hunnewell – In the 1880s, Hunnewell flourished briefly as a shipping point for Texas cattle. Located on the Kansas – Oklahoma border in Sumner County, the Leavenworth, Lawrence, and Galveston Railroad provided quick access to the Kansas City stockyards. Typical of cowtowns, the business district of Hunnewell reportedly consisted of one hotel, two stores, one barbershop, a couple of dance halls, and eight or nine saloons. Also typical was that violence was not uncommon and was the site of the Hunnewell Gunfight in 1884. Though the town never grew very large, it dwindled with the loss of the cattle trade. Today it only has about 65 residents.

Junction City – Junction City, located on the Kansas Pacific Railroad line, was a secondary shipping point for the cattle trade. The city, however, started long before the cattle trade was booming in Kansas. The first settlers arrived in the area in 1854, soon forming a town called Pawnee on the military reservation of Fort Riley. The first Kansas Territorial Capitol was built in Pawnee in 1855. However, that same year, Pawnee ceased to exist. Soon another settlement was built to the south of the fort, first called Manhattan, before changing to Millard, Humboldt, and finally to Junction City in 1857. In November 1866, the Kansas Pacific Railroad extended its line to Junction City, opening the settlement for more people. In the late 1860’s Junction City was a secondary shipping point to the more popular cowtown of Abilene, some 20 miles away. Today, Junction City is home to about 21,000 people. Nearby Fort Riley is still an active military post.

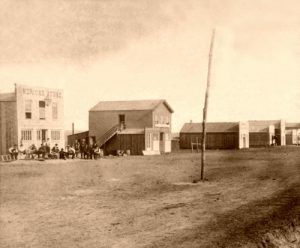

Newton. Kansas

Newton – Before the railroad arrived in Newton, a few homesteaders only sparsely populated the area. However, with the anticipation of the railroad’s arrival, several businesses were soon established. When the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad arrived on July 17, 1871, Newton became the shipping point of the immense herds of Texas cattle driven to Abilene before this time.

With the arrival of the large herds of cattle, cowboys, gamblers, “soiled doves,” and roughs of every variety. A portion of the fledgling city known as “Park” developed to accommodate these rowdy men and women, which held no less than 15 buildings devoted to “social amusement.” In total, the town boasted 27 saloons and eight gambling halls. These days, Newton was filled with tales rivaled only by Dodge City and was called the “wickedest city in the west.” This reputation came primarily from the August 1871 Gunfight at Hyde Park, which ultimately resulted in eight men being killed before, during, and after the event.

In 1872, the railroad was extended to Wichita, the next Kansas cowtown.

Salina – Salina started in 1857, and by 1870 it was one of the most flourishing towns in the state, featuring several new buildings in its business district. In 1872, Salina became a minor center of the cattle industry. The businessmen expended a good deal of money to secure the trade derived, but after gaining it, the people soon discovered that it was not such a desirable thing. Though the merchants’ business was significantly increased, the town became infested with such a crowd of disreputable male and female characters that whatever advantage was gained was more than counter-balanced by loss in morals. Though the people of Salina may have seen it that way, the rowdiness of Salina was mild compared to other Kansas cowtowns, as gunplay and carousing were sternly suppressed. In 1874 the cattle trade gravitated farther west, and Salina’s citizens rejoiced that its “cowtown” era had ended.

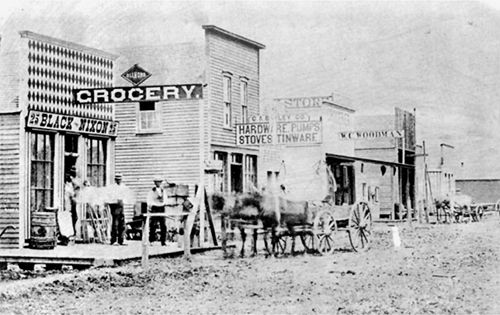

Wichita, Kansas Main Street, 1875

Wichita – The site of Wichita was first settled in 1864 when J.R. Mead opened a trading post there. Jesse Chisholm pioneered the Chisholm Trail the following year, and trade quickly developed the area. In 1865, a townsite was platted, and more people moved in.

A short-lived army post known as Camp Beecher was established nearby in 1868, but it was abandoned the following year. In 1872, the railroad arrived, and Wichita became the destination for Texas cattle driven north along the Chisholm Trail for shipment to eastern markets. The following year 66,000 head of cattle were shipped out of Wichita, twice as many as Ellsworth. Serving as a cowtown primarily from 1872 through 1876, the city developed a rough part of town called the “Delano” district that became the hub of gambling and drinking activities in Wichita. A dance hall proprietor named “Rowdy Joe” Lowe was among its cast of characters, who shot and killed his business rival, “Red Beard.” Working in Wichita for a time was none other than Wyatt Earp, from 1875 and 1876 before moving on to Dodge City. In 1876, the cattle trade moved westward, making Dodge City the new Queen of the Cowtowns.

However, Wichita continued to prosper and today is the largest city in the State of Kansas. It is known as the Air Capital of the World as it developed into a significant aircraft manufacturing hub. Though the city has become a major metropolitan area, a glimpse of its earlier Old West heydays can still be seen at the Old Cowtown Museum, depicting life in Wichita from 1865 to 1880. The museum provides 26 historic buildings and reproductions with period interiors, furnishings, machinery, photographs, live animals, and Old West re-enactors.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2024.

Also See:

Legends Of Kansas (our dedicated website to all things Kansas, because that’s where I grew up and where this website started)

Sources:

Awesome Stories

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

History on the Net

Kansapedia

Old West Kansas

Plains Humanities

Wikipedia