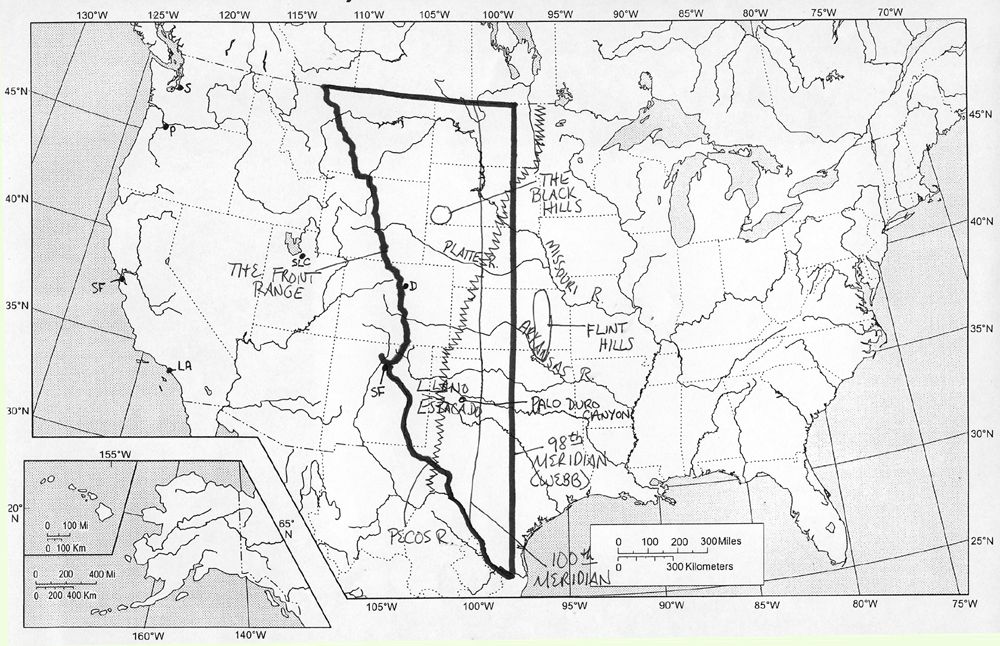

Great American Desert Map.

The “Great American Desert” was the term used by the people east of the Mississippi River to express their idea of the country westward when it was an unknown land. Carey and Lee’s Atlas of 1827 located the Great American Desert as an indefinite territory in what is now Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas. Bradford’s Atlas of 1838 indicates the great desert extending from the Arkansas River into Colorado and Wyoming, including South Dakota, part of Nebraska, and Kansas. Others thought the desert included an area 500 miles wide lying directly east of the Rocky Mountains and extending from the United States’ northern boundary to the Rio Grande.

Its boundaries changed from period to period, for Mitchell’s Atlas of 1840 placed the Great American Desert west of the Rocky Mountains. The section shown by the various geographies grew smaller yearly until only sandy plains in Utah and Nevada bore the name desert.

The history of this portion of the continent began with the earliest explorations in the New World. Spaniards made the expeditions following Christopher Columbus from the South. After Mexico and Florida had been discovered, Alvar Nunez was sent from Spain to explore Florida. His journey took him to the mouth of the Mississippi River, where he suffered a wreck, and only 15 of his men survived — eleven of these were killed by the Indians. The four remaining men were made prisoners and separated. Nunez, also known as Cabeca de Vaca, was carried by the Indians north into the great plains in sight of the Rocky Mountains. He and his companions reunited, escaped the Indians, and, working their way slowly, found the Spanish settlement in Mexico in 1836.

In 1538, Hernando de Soto left Spain to explore Florida. At about the same time, Coronado, inspired by Cabeca de Vaca’s tales, started north to find seven golden cities. His search for Quivira took him to what is now central Kansas.

Early in the 19th century, the United States government sent out exploring expeditions. One of these was under the command of Lieutenant Zebulon Montgomery Pike, who, in 1806, went west from St. Louis, Missouri, to hunt the source of the Arkansas River. In his description of the country, he wrote, “From these immense prairies may arise one great advantage to the United States, viz: The restriction of our population to some certain limits, and thereby a continuation of the Union. Our citizens, being so prone to rambling and extending themselves on the frontier, will, through necessity, be constrained to limit their extent to the west to the borders of the Missouri and Mississippi. At the same time, they leave the prairies incapable of cultivation to the wandering and uncivilized aborigines of the country.” His explorations are referred to as Pike’s Expedition.

The report of Major Stephen H. Long’s Expedition in 1819 and 1820 verified the words of Pike. He considered a significant part of the country unfit for cultivation and uninhabitable by people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence. In speaking of the whole section from the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains, he said, “From the minute account given in the narration of the particular features of this expedition, it will be perceived to be a manifest resemblance to the deserts of Siberia.”

Washington Irving, in his Astoria, published in 1836 and founded on a brief tour he made on the prairies and into Missouri and Arkansas, said:

“This region, which resembles one of the ancient steppes of Asia, has not inaptly been termed ‘The Great American Desert.’ It spreads forth into undulating and treeless plains and desolate sandy wastes, wearisome to the eye from their extent and monotony. It is a land where no man permanently abides, for, at certain seasons of the year, there is no food for the hunter or his steed.”

Pike, Long, and Irving’s reports did much to form public opinion regarding this unknown land. Pike and Long’s expeditions were practically the last exploration work done by the government for several years. While the government was idle, private enterprise was working its way westward.

Westward travel was accelerated in 1849 when gold was discovered in California. Previously, overland travel had been very light, but in 1849, it was roughly estimated that 42,000 persons crossed the plains.

The trip was full of every kind of danger. Indians, storms, and disease attacked caravans, but many returned to settle in some favored spots. The lands along the streams were the first to be taken by the settlers. Gradually, the country yielded to the influence of law and order. Even the most dismal spots were developed into gardens of usefulness and beauty by the work of irrigation; the government began doing much for the protection of forest and range, and by feats of engineering, a variety of rich mines were opened; railroads crossed seemingly impassable plains; factories of all kinds sprung up; gases from underground were controlled for light and fuel; educational institutions opened their doors to millions of children, and churches of all denominations were erected. The free library, the telegraph, the telephone, rural mail delivery, and modern times’ complexities were soon crowded upon the Great American Desert.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2024.

Also See:

Adventures in the American West

About the Article: The majority of this historic text was published in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. However, the text that appears here is not verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing has occurred.