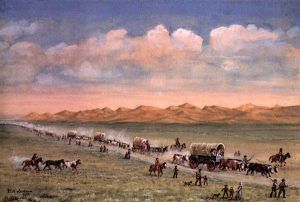

“So the Oregon Trail was blazed and tramped—traders, trappers, gold-seekers, missionaries, colonists—until the highway stretched from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean. Years passed, and railroads supplanted the old Oregon Trail; its very location was forgotten, disputes arose. Then an old man, almost eighty, clambered into a prairie schooner, made in part of some in which the pioneers had journeyed westward, and the Oregon Trail was retraced and marked with monuments that a people and a nation may not forget.”

— Howard R. Driggs, Covered Wagon Centennial and Ox-Team Days, The World Book Company, 1932

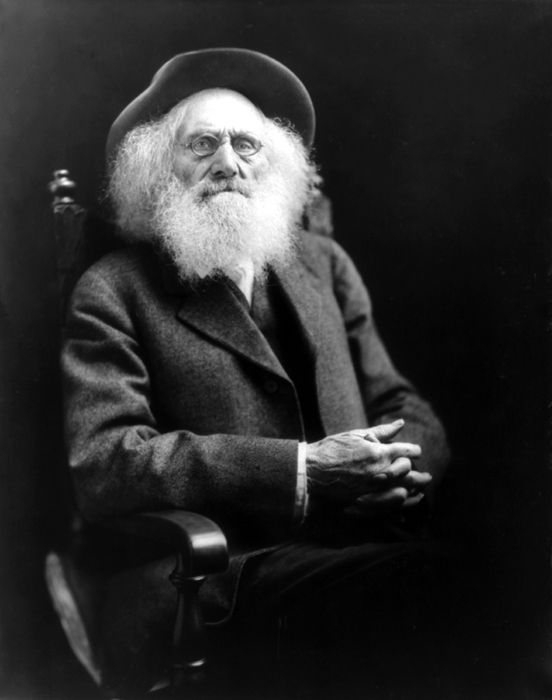

Ezra Meeker was a pioneer who first traveled the Oregon Trail by ox-drawn wagon as a young man in 1852. Fifty years later, he would make the trip again and again, repeatedly retracing the trip of his youth, and worked to memorialize the Trail.

Ezra Manning Meeker was born near Huntsville, Ohio, on December 29, 1830, the fourth of the six children born to Jacob and Phoebe Meeker. His father was a farmer and a miller. The family moved to a site close to Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1839. He had little schooling in his early years and started working odd jobs, including working as a printer’s devil and delivering newspapers for the Indianapolis Journal.

He married his childhood sweetheart Eliza Jane Sumner in May 1851, and the couple would eventually have six children. In 1852, the couple, their seven-week-old son, and Ezra’s brother, Oliver, joined a wagon train destined for Oregon Territory. With their wagon, they had two yokes of oxen, one of cows, and an extra cow. The wagon train traveled together by an informal agreement without a wagon master.

After five long months on the trail, the entire party survived the trip and arrived in Oregon. Ezra first went to work unloading a ship that had docked at Portland and then moved to the nearby town of St. Helens, where he worked with his brother on constructing a wharf.

In January 1853, he made his first land claim about 40 miles downriver from Portland, on the current site of Kalama, Washington, to establish a farm. However, this was short-lived. In April 1853, when the brothers heard that the lands north of the Columbia River would become Washington Territory centered on the Puget Sound, they moved north, first settling on McNeil Island, not far from the thriving town of Steilacoom. Oliver remained on the island to build a cabin while Ezra returned for the family and possessions and sold their old claims at Kalama.

Later in 1853, the Meeker brothers received a three-month-old letter from their father, Jacob, stating that he and other family members wanted to emigrate. Oliver returned to Indiana the following year to help with his family’s move. In August 1854, Ezra Meeker received word that his relatives were en route but were delayed and short on provisions. He quickly went to their aid and found them close to the first Fort Walla Walla (near Richland, Washington), where he learned that his mother and a younger brother had died along the Trail. He then guided the survivors the rest of the way.

Jacob Meeker saw limited prospects on the island, took claims near Tacoma, and operated a general store in Steilacoom. On January 5, 1861, Oliver Meeker drowned while returning from a buying trip to San Francisco when the ship he was traveling on sank off the California coast.

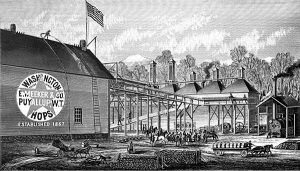

The Meekers had borrowed to finance Oliver’s trip and, in 1862, lost their money and land. The family then secured squatter’s claims in the Puyallup Valley. There, they began to grow hops used in beer brewing. The fertile soil and temperate climate of the valley proved ideal for hops, and not only did the plants thrive, but the Meekers were also able to obtain four to five times the usual yield. More farmers in the area also began to grow hops bringing prosperity to the valley.

In the next several decades, Ezra Meeker cornered the hop market, amassed a large fortune, and became a merchant, bank president, promoter of the Northwest, lecturer, and proponent of roads and railroads.

In 1877, Meeker filed a plat for a townsite and named it Puyallup, using the local Indian words for generous people. Ezra Meeker became the first postmaster. He also donated land and money towards town buildings, parks, a theater, and a hotel, while defraying the start-up costs of a wood products factory. Nearly a century later, The Ezra Meeker Historical Society wrote of him in 1972:

“During those years, Mr. Meeker became a dynamic force in the community and had a part in almost everything that happened in the valley. Restless, forceful, and a natural leader, he became a prime mover, galvanizing the citizens of Puyallup into action on such vital problems as the building of streets, roads, homes, schools, and businesses and transforming the forest into one of the most progressive small communities in the state. If he was not leading an undertaking, he was sure to be a busy member of some committee working on it.”

By 1887 he and his wife began to build a large mansion in Puyallup, the cost of which was $26,000, a substantial sum at the time. An Italian artist lived with the Meekers for a year, painting careful details on the ceilings. The Meekers moved in during 1890, the same year Puyallup was formally incorporated. Ezra Meeker served as the first mayor of Puyallup and was elected to a second term in 1892.

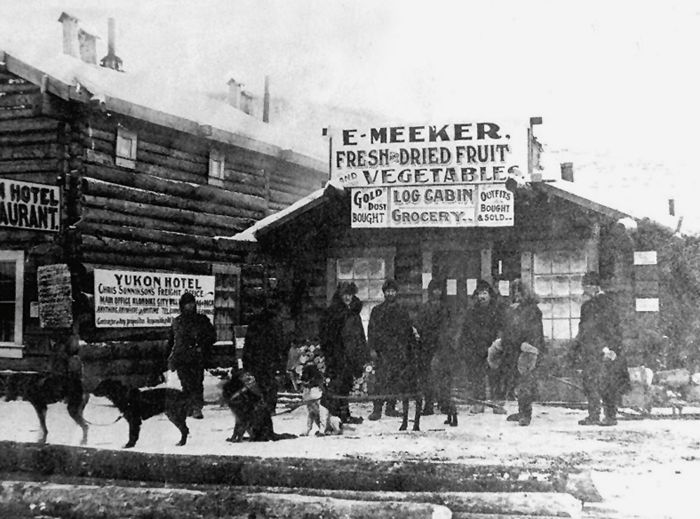

In 1891 an infestation of hop aphids destroyed Meeker’s crops and other regional farmers. Meeker had lent money to many growers who could not repay him. The problems in the valley were worsened by the Panic of 1893, a severe worldwide depression. Business after business in which Meeker had invested failed, such as the Puyallup Electric Light Company. As a result, he lost much of his fortune and eventually his lands to foreclosure. Meeker then turned his attention to supplying vegetables to miners in the Yukon and Klondike goldfields.

The Meeker family also founded a company to buy and sell mining claims, though they knew little about the trade. In 1897, Meeker and his sons journeyed to the Kootenay country of southeastern British Columbia and began to work their claims. Later, they opened the Log Cabin Grocery in Dawson City during the Klondike Gold Rush.

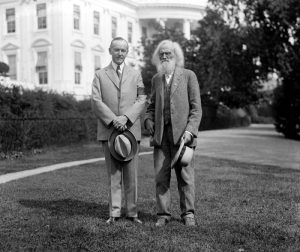

In the early 1900s, Meeker decided that the Old Oregon Trail needed to be marked and preserved to preserve the history of the westward movement. He dedicated himself to this goal for the rest of his life, meeting with Congress and Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Calvin Coolidge.

To interest the nation and raise funds for his project, he traveled the Oregon Trail by ox team in 1906 and again in 1910, in an airplane in 1924, and at the time of his death in 1928, at the age of 97, he was beginning a trip in a Ford automobile with a covered wagon on the back.

In the meantime, his mansion was put up for sale in 1903 but remained in family hands for several years. When Ezra made his Oregon Trail trip in 1906, rooms were rented out to boarders. After his wife, Eliza, died in 1909, Ezra left the building, leaving it in the hands of a daughter and son-in-law to dispose of. In about 1912, it was leased to be used as a hospital. In 1915 it was sold to the Washington and Alaska Chapter of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic to be used as a home for widows and orphans. The mansion still stands today, serving as a museum at 312 Spring Street.

During his lifetime, he was also a founding member and president of the Washington Historical Association. At the time of his death, he was the founder and president of the Oregon Trail Monument Association, the predecessor of today’s Oregon-California Trails Association (OCTA). He was also a writer, chronicling the events of his day in books, newspapers, magazine pamphlets, and agricultural journals.

At the time of Meeker’s death, he was living in Seattle, Washington, where he died of pneumonia on December 3, 1928, just a month short of his 98th birthday. His remains were taken to Puyallup, where he was interred beside his wife, Eliza Jane, in Woodbine Cemetery. Their gravestone reads: “They came this way to win and hold the West.”

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2023.

Also See:

Ezra Meeker and a converted Model A Ford, which we planned to use for his 1928 trip before his death.

Crossing the Great Plains in Ox-Wagons

Landmarks Along the Oregon Trail

Oregon-California Trail Timeline

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

Sources: