From the Colorado Department of Transportation

Native Trails: Pre-history to 1850s

The heart of the Rocky Mountains by the Detroit Photographic Co., 1901.

Across Colorado’s prairies and mountains, layers of asphalt cover many of the paths first cut by the region’s indigenous peoples centuries ago. One early route originally followed by the Ute Indians illustrates the transformation of a footpath to a highway over a millennium. Nearly 1,000 years ago, the Ute traced a path from Estes Park over the Continental Divide to Middle Park. Subsequent European and American explorers, trappers, and settlers followed the same route, eventually naming the trail the Ridge Road. By the mid-1920s, federal and state bureaucracies took the romance out of travel and classified the auto road as US Highway 34. Other modern highways that trace their lineage back to the Ute include a portion of US 24, crossing the Rockies west of Colorado Springs along an ancient tribal route to modern-day South Park; the trail over the 10,032-foot Cochetopa Pass that is today’s State Highway 114; and US Highway 160 from the Rio Grande to the San Juan River over the Continental Divide by Wolf Creek Pass.

In 1540, the first Europeans arrived in Colorado. Twenty-two members of a scouting party under the command of General Don Francisco Vasquez de Coronado wandered across southeastern Colorado in search of the Seven Cities of Cibola. Over the next 150 years, the Spanish fought to control their Pueblo Indian serfs, battle other Native tribes, and avoid much exploration beyond Santa Fe, the capital of New Spain’s Province of New Mexico. In 1694, after putting down a Pueblo Indian revolt, Governor Don Diego de Vargas led an expedition from Santa Fe upriver along today’s U.S. Highway 285. By 1706, a group of colonists established Colorado’s first European settlement, a trading post 100 miles south of Pueblo. For the remainder of the 18th century, conquistadors and friars followed their own routes through the San Luis Valley. Spanish trailblazers like Juan de Ulibarri, Fathers Silvestre Escalante, Francisco Dominguez, and Don Juan Bautista de Anza provided early descriptions of Colorado’s geography, plants, and wildlife.

While the Spanish built roads in California and New Mexico, the land north of Santa Fe was too wild, too distant, and seemingly lacked any resources for the Spanish to control and maintain.

Emigrant and Trade Routes

Through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the United States acquired a vast area of the continent, including most of eastern Colorado. During 1806-07, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and his men crossed much of southern Colorado, establishing Pike’s Stockade at the Conejos River in the San Luis Valley. They were arrested and later set free by Spanish authorities.

In 1820, President James Monroe sent Major Stephen H. Long to explore the southwestern boundary of the Louisiana Purchase. When Long’s party came up the South Platte River, Long dismissed the high plains as the “Great American Desert,” a lasting perception in many Americans’ minds for decades to come. Undeterred by Long’s opinion, a handful of solitary outsiders making a living trapping beaver and trading with the Natives followed.

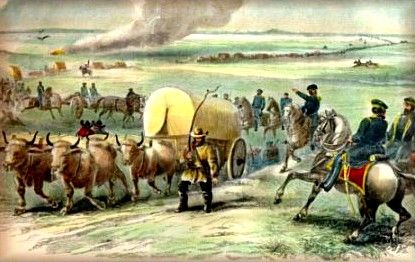

Over the next two decades, subsequent sojourners would blaze two important paths into Colorado: the Smoky Hill Trail from Leavenworth, Kansas, and on to Cheyenne Wells, Hugo, Limon, Bennett, and Denver; and the Overland Trail from South Platte, beginning at latter-day Julesburg to Greeley and up the Cache La Poudre River to LaPorte. The mountain man era ended abruptly in the late 1850s with the arrival of the first gold-seekers wagons with “Pike’s Peak or Bust” red-chalked on their sides. In 1860 alone, nearly 70,000 survived raiding parties, inclement weather, starvation, and drought to take a chance on finding gold—following routes first cut by the trappers.

Santa Fe Trail

Perhaps the most important of the early trails, the Santa Fe Trail, was the primary link between St. Louis, Missouri, and the Spanish-Mexican outpost of Santa Fe in the 1820s. In the late summer of 1821, William Becknell led a trading party from the banks of the Missouri River through southern Colorado on to Santa Fe. By November of that year, he reached Santa Fe and established a caravan trade that lasted more than 40 years.

By the 1830s, the northern, or Mountain Branch, of the Santa Fe Trail was the first route into Colorado from the east. The trail was a link between New Mexico over Raton Pass to the markets of the Missouri Valley and the trading posts along the Arkansas River. In 1821, American pack and wagon trams first plodded along the Santa Fe Trail in southeastern Colorado along the route later used by US 50 and 350.

Between 1829 and 1834, William Bent established his Fort on the Arkansas River and added a new chapter to the history of the Santa Fe Trail. By the early 1830s, Becknell’s original route had fallen into disuse due to Kiowa and Comanche tribesmen on the warpath. Nearly 100 miles longer, the route by way of Bent’s Fort was safer from Indian attack, and since it followed the Arkansas River, Timpas Creek, and the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, there was less likelihood of stock dying of thirst. As with other trails, the subsequent march of the railroad put the trail into disuse. By 1880, the first train blazed into Santa Fe, and with the arrival of the automobile, the route of the old trail is better known today as US 50 and 350.

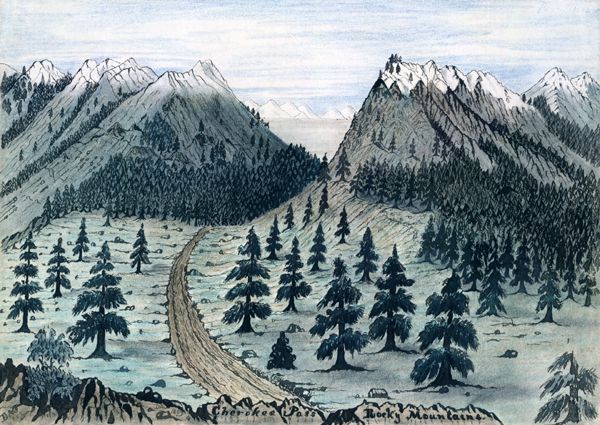

Cherokee Trail

Cherokee Trail.

As well traveled as the Santa Fe, but not as storied, the Cherokee Trail began on the Arkansas River near the current Arkansas–Oklahoma border. French explorers of the mid-18th century were among the first Europeans to follow this route through Colorado. The Cherokee Trail branched off the Santa Fe Trail at La Junta. From there, the trail continued up the Arkansas River, followed Fountain Creek to Colorado City, and on through Denver to Virginia Dale near the Wyoming border. The Cherokee Trail eventually reached the goldfields near Sacramento, California.

U.S. Highway 50 follows the Cherokee Trail from the Kansas border to the east side of Fountain Creek from Pueblo to the town of Fountain. A subsequent stage road continued up the west side of Fountain to Colorado City before the founding of Colorado Springs. In the wake of the automobile, the original alignment of US Highway 85 (now Interstate 25) followed the path of the Cherokee stage route through this portion of southern Colorado.

Smoky Hill Trail

There were three branches of the Smoky Hill Trail in Colorado: North, Middle, and South. Gold Seekers, in 1859, followed the Middle Smoky along the Smoky Hill River out of Kansas to Old Cheyenne Wells (north of the current town of Cheyenne Wells) in Colorado. Although it was the most direct to gold camps, the Smoky Hill was known as “The Starvation Trail.” During its greatest use during the 1860s, the Middle Smoky measured more than ten miles wide, depending on local conditions. The trail followed the contours of the surrounding country, tracing ridges on the lower ground while avoiding surrounding sandhills. Open to all the elements, more people died from hunger and thirst than Indian attacks along this route. Three modern highways follow the Smoky Hill Trail through Colorado: US 40 from the Kansas border to Limon, State Highway 86 west to Elizabeth, and State Highway 83 from Parker to Denver.

Overland Trail

The Overland Trail and the branch of the Oregon Trail from the Lower California Crossing at Brule, Nebraska, ascended the south bank of the South Platte River before entering northeastern Colorado. The Overland and the Oregon Trails separated at the Upper California Crossing near Ovid, Colorado. The Overland continued along the south side of the river to Denver. The Oregon Trail crossed the South Platte River and re-crossed the northern border of Colorado into Nebraska. The original Overland Trail ran along the course of today’s US 138 to US 6 in northeastern Colorado.

From the late 1850s into the mid-1860s, wagons and stages followed a bypass of the Overland Trail known as the Fort Morgan Cutoff. Along a diagonal line from Fort Morgan to Denver, the cutoff shaved 40 miles off the trip. Modern US 6 is approximately 40 miles west of the Fort Morgan Cutoff, built in a region of heavy sand that stage and freight wagons could not have negotiated during the mid-19th century.

After the Overland Stage crossed the Fort Morgan Cutoff, it headed toward Denver. The stage then turned back north along the west bank of the South Platte River to Longmont and Loveland. This portion follows the alignment of today’s Interstate 25. Past Loveland, the stage headed west of Fort Collins to LaPorte on to the Wyoming state line. That divergence is modern US Highway 287 from Laporte into Wyoming.

Trapper’s Trail

Other trails lasted only long enough to be remembered solely by their highway designation. The Trapper’s, or Taos, Trail went from Taos, New Mexico, to Fort Garland in the San Luis Valley along today’s State Highway 159. The Trapper’s Trail eventually divided at the Huerfano River, with one branch following the river to Fort Reynolds and the other going to Pueblo. By 1860, an ancient trail, believed to be the first used by white settlers in Denver, became a part of the Trapper’s Trail. The trail closely paralleled modern Kalamath Street, entering Denver near the location of 11th Street.

The Native and Mountain Man trails are the well-worn paths that most Coloradoans still follow. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States Military explored new pathways in and around Colorado, and detailed existing routes are still in use today.

Military Roads and Surveys

President Thomas Jefferson’s desire to know more about the northern plains prompted the Lewis and Clark expedition. Around the time Lewis and Clark returned East, Army Lieutenant Zebulon Pike was going to the central Rockies to study that portion of the Louisiana Purchase. In mid-November 1806, Pike and his men would discover the peak destined to bear his name and reach the headwaters of the Arkansas River near today’s Leadville. In 1820, a party led by Major Stephen H. Long pushed farther into the unexplored country, bringing back tales of Colorado as a great desert. In subsequent decades, Lieutenant John C. Fremont and Captain John Gunnison led other military parties to give the American people more detailed information about the far-off Rocky Mountains. Their reports, however, did little to stimulate mass migration to the region.

As stated in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, signifying the end of the war with Mexico, the Rockies of New Mexico and Colorado became the property of the United States. In the late 1840s and early 1850s, the United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, led by Captain Howard Stansbury, conducted survey supply routes across Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. Officers under Stansbury, like John C. Fremont, John Gunnison, and Edward G. Beckwith, recorded their observations and experiences as they made their way through the mountains. After exploring some of the highest points of the Continental Divide, Gunnison and a handful of his men were killed by a band of Paiute Indians along Utah’s Sevier River. Gunnison’s name lives across the area he and his men first surveyed.

Congressional passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 was this region’s first taste of federal funding for road construction. The Act is best remembered for formally organizing the two territories and clearing Indian land titles. It also placed the land, later known as Colorado, under the jurisdiction of Kansas Territory. The following year, the federal government sought to build and improve existing trails in Kansas and Nebraska Territories. In 1855, Congress authorized a $50,000 appropriation for improvements to the road between Fort Riley, Kansas, and Bent’s Fort in Colorado. Soldiers conducted surveys and escorted civilian construction parties on this military road but performed no clearing or building.

The federal government maintained interest in located paths and wagon routes over the Rocky Mountains despite the coming Civil War In 1861, Captain E. L. Berthoud and his guide, Jim Bridger, surveyed the Rockies in search of a route to the Utah Territory. Beginning at the headwaters of Clear Creek west of Denver and traveling north, Berthoud’s party discovered a pass through the Rocky Mountains in May of that year. By September, Berthoud’s report to the U.S. Army detailed a 413.25-mile route from Clear Creek to Salt Lake City. However, it took another 13 years before the first stagecoach conquered the 11,315-foot high pass named in Berthoud’s honor.

One subsequent military route important in Colorado highway history cut across remote northeastern Colorado. The U.S. Army built the Government Road (now known as State Highway 13) between 1880 and 1884 to protect settlers in the wake of the Meeker Massacre of 1879. The original Government Road ran from Ft. Steele in Wyoming to the San Juan Mountains in southwestern Colorado.

Mining-Related Roads

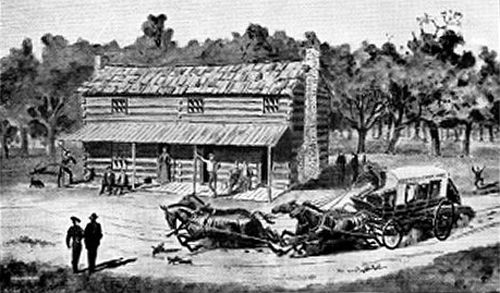

Pike’s Peak Express at Leavenworth, Kansas.

The gold rush of the late 1850s brought the stage lines into the mountain mining camps. In the spring of 1859, the Leavenworth and Pikes Pike Express began carrying passengers, mail, and freight from Leavenworth, Kansas, west over the prairie before ultimately arriving on the north banks of Cherry Creek. The new alignment forced stage company employees and passengers to pitch and provide necessary roadwork. One of the passengers from New York, Horace Greeley, was said to have swung a pick and shovel to help clear the road. Laid out by B.D. Williams, who later became Colorado’s first territorial delegate to Congress, the Leavenworth and Pikes Peak line follows the general route of today’s U.S. 36. In 1864, the Butterfield Overland Dispatch hauled its first freight and passengers along the Smoky Hill route. By late 1866, Wells Fargo had bought out the small operators and established a monopoly over all transcontinental stage lines in Denver.

During the 1860s, the stagecoach expanded beyond the eastern plains and Denver to serve the most isolated mining communities in and along the Rockies. The miners themselves carved the roads out of the mountains by hand. Grades were so steep on some crude mountain roads that drivers had to drag huge logs to control the occasional breakneck ride.

The relative speed and comfort of the railroad ended the dominance of the stagecoach across most of the West. Nevertheless, the stage remained the chief means of travel throughout Colorado’s mountainous and sparsely populated areas. Along the mining towns of the Rockies, stages operated by speculators Billy McClelland and Bob Spottswood ran from Denver to Morrison over the route of today’s US 285, through Turkey Creek Canyon to Fairplay. In 1873, McClelland and Spottswood expanded their passenger and express coaches over the Continental Divide by way of what is now US 50 to Salida and then northward via modern US 24 from Granite to the town of Oro. The partnership later established another line between Colorado Springs and South Park that follows US 24. After he served as Colorado’s second territorial governor, John Evans built another important toll road from Morrison along Bear Creek to the mining camps of Idaho Springs, Silver Plume, Georgetown, Central City, and Blackhawk in 1873. The road follows the general alignment of modern State Highway 74.

Buried under a cloud of locomotive steam, stagecoaches slowly faded from the scene. Nevertheless, in Colorado’s most remote locations, they served isolated farmers and miners well into the 20th century. As late as 1918, a stage line between 30 miles of Rifle and Meeker competed with the occasional brave automobile owner along the Government Road, now known as State Highway 13.

Railroads and the End of the Wagon Trail

During the 1950s, Colorado campaigned and crossed its fingers while it waited for the federal government to expand the national interstate highway system beyond Denver. It was not the first time the state lobbied and fretted over its transportation fate. Nearly a century earlier, in the late 1860s, Colorado fought an economic life-and-death struggle with its neighbor to the north, Wyoming, over who would benefit from the first railroad line in the Rocky Mountain West. The Rocky Mountains were the ultimate double-edged sword for the state’s promoters. The peaks lured miners and tourists but caused concern among road and rail builders.

Union Pacific Train, the late 1800s.

In the spring of 1869, bridging the United States by rail at Promontory Point, Utah, placed Colorado at a crossroads. The Union Pacific Railroad’s construction of a transcontinental line over the easy grade of Sherman Hill in Wyoming made Colorado panic. Territorial residents knew that Colorado needed the railroad to survive. A line from the Union Pacific station in Cheyenne to northern Colorado would allow the rail company to control traffic between the mining camps and eastern markets. By June 1870, Union Pacific built the first rail line in the state connecting Denver to Cheyenne.

Panic turned to action as connections with Kansas City and St. Louis, Missouri, came later that year through the completion of the Kansas Pacific system. The railroad coming to Denver provided the impetus for the city to become the Rocky Mountain West’s urban center. Reflecting the changes brought by the railroad, during the 1870s, Denver’s population increased by 700% to almost 36,000 residents.

Silver outshone gold during the 1870s and 1880s as mining camps in the mountains and southwest of Denver boomed. General William J. Palmer led the construction of the Denver & Rio Grande system to create a north-south rail artery along the Front Range. To reach the silver camps high in the mountains, Denver & Rio Grande was the first rail company to lay narrow gauge lines along the steep cliffs. Measuring three feet across, the narrow gauge line had to “curve on the brim of a sombrero” along the canyons to reach the inaccessible mining camps.

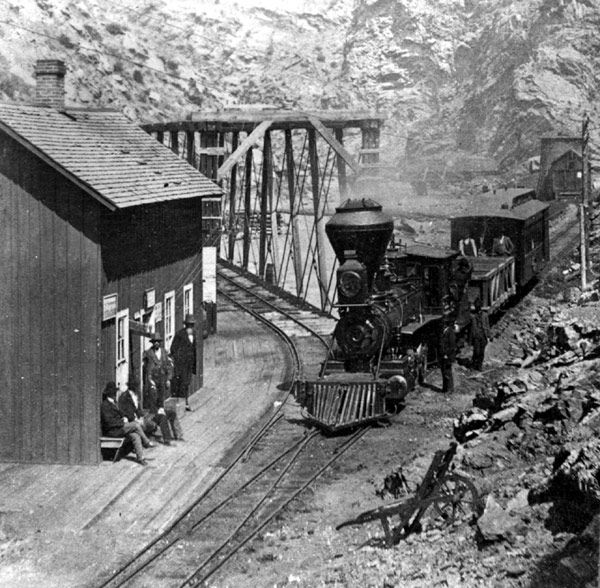

Narrow Guage Railroad, Idaho Springs, Colorado.

By the early 1880s, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe and the Union Pacific rail lines linked the state’s agricultural northeast and southeast portions to South Platte Valley and Denver. This construction set the foundation for the state’s agricultural industry, notably the dry-land production of sugar beets and winter wheat.

The narrow-gauge lines also left a legacy to the automobile. As the silver boom went bust in the 1890s and production of other metals began to wane, many small railroads abandoned their lines. Following World War I, the state and private speculators removed miles of track and transformed these routes into state highways or jeep roads across the Continental Divide and on the Western Slope.

Many rail alignments served as state highways from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s, resulting in State Highway Engineer Charles Vail’s decision to add 4,400 miles to Colorado’s highway system. Some roads, notably a route between Colorado Springs to Victor and an abandoned portion of US 50 west of Mack to the Colorado-Utah border, serve as county roads. Portions of old, narrow-gauge lines still in use as state highways include State Highway 67, south of Divide; Colorado 82 between Basalt and Aspen; and State Highway 103 from Clear Creek to Georgetown.

Commerce and technology brought people to Colorado. However, it took organization and regulation to respond to westward changes. These forces crept toward one another as the 19th century wore on.

By the Colorado Department of Transportation edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2024.

Also See:

Colorado Forts of the Old West

Discovery of the Rocky Mountains