Spain, the first European nation to colonize the New World, pushed northward from Mexico to Pueblo Indian villages and beheld the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River 80 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Spain drew no boundaries for New Mexico. The province stretched as far to the north as military expeditions could enforce periodic recognition of Spanish power among the Indians on the plains and in the mountains.

The exact date of the earliest Spanish contact with the Ute Indians of Colorado remains in question, but it has been established that the introduction of the horse to the Utes dates from as early as 1640. Having seen horses and learned of their utility as mounts, the Indians were eager to procure these animals. Subsequently, Spanish traders followed trails into distant Ute villages. Indians made return calls at New Mexican towns such as Taos, bringing buckskin, dried meats, furs, and slaves to barter for horses, knives, and blankets. As a result of trading, during the 17th and early 18th centuries, Spanish-Ute relations were characterized by peaceful interaction. The relative harmony between the two cultures aided the Spanish in their attempts to explore the frontier north of New Mexico.

By the middle of the 18th century, rumors of mineral wealth in the distant San Juan Mountains drifted into the New Mexican capital of Santa Fe. Responding to these reports, Juan de Rivera conducted three expeditions into the southern Colorado Rockies between 1761 and 1765. He took soldiers, traders, and padres north, via Taos and the San Juan River, past the La Plata Mountains to the Dolores River. He then followed the Uncompahgre River to its confluence with the Gunnison River. In the vicinity of the Gunnison River in 1765, the expedition met a band of Ute and other mountain Indians, and a brisk trade was established. However, the party returned to New Mexico discouraged, as they found little in the way of precious metal. After these initial expeditions, little is known about Spanish activity in Colorado; from time to time, New Mexican records show that the veterans of the Rivera expeditions conducted trade with the northern Indians.

At the same time, Rivera searched for gold and silver in Southwest Colorado; her European rivals were making inroads into the territory surrounding Spain’s New World empire. By the mid-18th century, England, including the American colonies, possessed considerable North American territory, moving with concerted interest into the Northwest Territories. France had established herself as a North American power in Canada and had begun exploration southward with obvious intentions toward Spanish holdings along the Gulf of Mexico. Russia explored and took possession of west coast territory in present-day Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and northern California. Conflict and empire predominated the history of the European continent. North American territories acted as one stage for the unfolding of this historical drama.

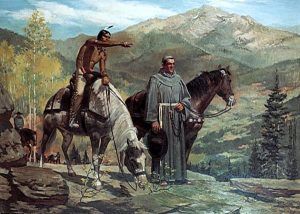

Fifteen years after the first Rivera expedition, Fathers Francisco V. Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante hoped to discover a mission route that would establish a strategic communications link between Santa Fe and the missions of California. Convinced that a westward course to California in the latitude of the Hopi villages was impractical because of Hopi hostility and that a route through Ute country north of the Colorado River would be more feasible, Dominguez and Escalante set out in 1776 upon what would become a five-month, 2,000-mile journey that would take them through much of present western Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. Although the purpose of the Dominguez-Escalante mission was not accomplished, the expedition did have long-range effects on the history and development of the southwest. The explorers revealed the vast inland area’s geography, potential resources, and inhabitants. The information, accounts, and maps preserved from the expedition would provide others, New Mexicans and Americans alike, with a base to fulfill the Padres‘ dreams. After the expedition’s discoveries, traders from New Mexico who went to the distant Ute country were undoubtedly influenced by Escalante’s journey. The route of the Escalante Trail followed in part, soon became known by American traders as the Old Spanish Trail. This historic route symbolized much of what was to become the larger drama of the southwest — a contest of Empires. When nations gambled for imperial stakes in land and commerce, first-footing gave claim, and occupancy meant possession. In such a time, the exploring man of commerce served more effectively than the soldier.

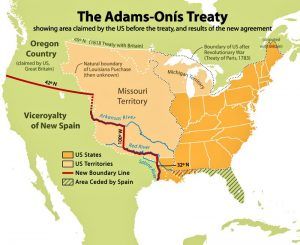

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Spain had become more protective of the northern buffer of her Mexican holdings. After 1803 and the Louisiana Purchase, the Spanish government shifted its earlier ban on Ute trade; Americans were forbidden the fruit of southwestern commerce. The Adams-Onis Treaty ratified in 1819, established an official boundary between Spanish and American possessions in the southwest. This agreement left the southern plains, a substantial portion of the western Rocky Mountains, and the entire western plateau region of the American Southwest in Spanish hands. With a demarcation set, the Spanish made little attempt to maintain defenses of their northern borderlands. Although this treaty remained in force until the American annexation of Mexican lands following the Mexican-American War in 1848, such diplomatic agreements were given little notice by a new type of frontier explorer, the fur trapper. Following potentially beaver-rich streams rather than guided by political boundaries, the fur trappers, Americans, French-Canadians, and New Mexicans alike, explored areas of western Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming as early as 1812. The Green River region below the Wind River Range in Utah had not been systematically trapped by 1821. Yet, when Mexico gained its independence that year, new diplomatic relations between the United States and Mexico opened the area as a new commercial frontier. Responding to reports of rich beaver streams in the Green River Valley and hoping to establish successful trade relations with the New Mexican government, American entrepreneurs came to Santa Fe in 1821 when New Mexico became a Mexican territory.

The earliest fur-trading expeditions were based in the New Mexican trading towns of Santa Fe and Taos, strategically positioned at the terminus of the newly opened Santa Fe Trail. With a convenient commercial link to U.S. and international markets, the fur trading business developed rapidly. William Becknell, forgetting about the Santa Fe Trail almost as soon as he had found it, set out to locate a practical route to the beaver-rich Green River Valley other than the Old Spanish Trail. In 1824, he led a party north from Taos to the Green River. In August of that same year, William Huddart, with 14 others, left Taos, traveled north through the San Luis Valley, crossed the Cochetopa Hills at an ancient Ute and buffalo traverse, and by way of the Gunnison and Uncompahgre Rivers pushed on into eastern Utah to the Green River. At about the same time, an expedition led by Kit Carson and Jason Lee followed the Old Spanish Trail along Escalante’s route north and met Antoine Robidoux at the mouth of the Uinta River in Utah. By the end of 1824, at least six parties of trappers had traveled north from Santa Fe or Taos, through southwestern Colorado, into the Green River region by way of the Old Spanish Trail or the northern extension of that trail via the Cochetopa Pass route, also known as the Trappers’ Trail. Besides those of Huddart, Becknell, and Carson, there were groups led by William Wolfskill, Etienne Provost, and Antoine Robidoux.

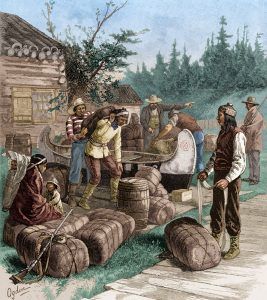

Through the mid-1820s, the fur brigades of Provost, Robidoux, and Becknell repeatedly worked the Green River until more extensive trapping expeditions invaded this choice beaver country. Such trapping parties were directed by the future Fur Barons, William Ashley, and John Jacob Astor. In the spring of 1824, Ashley sent his men out to trap the region and then arranged to meet them at a “rendezvous” on Henry’s Fork of the Green River to exchange their furs for the trading goods he had brought from St. Louis, Missouri. The rendezvous system proved so successful that extensive trapping became the order of the day. Large operations such as the Hudson’s Bay Company and the American Fur Companies reaped huge profits from the fur trade. By 1826, however, many of the northern streams became “trapped out,” and by the early 1830s, the prices of pelts had begun to drop.

The overexploitation of streams and the intense competition of the large fur companies prompted many trappers and traders to move south from the Green River Valley. Antoine Robidoux, maintaining a trading post at Taos, built a fort near present-day Delta, Colorado, in 1828. From there, he sent out trapping parties along the Colorado River as far south as the Gila River and on the various streams in closer proximity to the fort.

Fort Uncompahgre, Colorado’s first and America’s second “general store” west of the Continental Divide, served as a trading and supply establishment for the “free trappers” in the vicinity and was located on the north-south trailway used by trappers traveling from New Mexican settlements north. By the mid-1830s, Robidoux had established a direct arrangement with his brother’s trade establishments in St. Louis and Fort Osage, Missouri. Passing the New Mexican settlements, the Robidoux brothers freighted supplies directly through the Gunnison River by Cochetopa Pass to the Fort. Until its destruction in 1844, the fort also served as a supply base for immigrants moving westward to California.

Although the fur trade excitement had declined, Antoine Leroux, Kit Carson, Charles Autobees, Tom Tobin, and “Uncle Dick” Wootten, along with Robidoux, continued to trap the Gunnison River area in the Fort Robidoux district during the 1830s and 1840s. While these last efforts at free trapping were being undertaken, several mountain men who had blazed trails important to the fur business had turned their attention to California, a distant source of commercial interest.

Although New Mexicans were the first to inaugurate the commercial trade to California, Americans quickly saw its potential. New Mexico’s Governor Antonio Armijo began traffic to California by annual caravan in 1829 and 1830. Utilizing knowledge gained from fur trading explorations, Armijo and his party moved up to the Chama River from the New Mexican outpost at Abiquiu. They continued on the traders’ trail until they reached the San Juan River, which they followed through parts of southwestern Colorado in the Four Corners region. They pushed onto the Colorado River and traversed the Old Spanish Trail to California.

Directly on Armijo’s heels were parties among its members, including explorers such as William Wolfskill, Ewing Young, Kit Carson, and Tom “Peg-Leg” Smith. Although their routes varied substantially at times with those of the New Mexican traders, the general course was northwesterly from Taos to the Colorado River, crossing sections of southwestern Colorado and, via the Old Spanish Trail, onto California. The Young-Wolfskill party of 1830-1831 is credited with covering the entire distance of the Old Spanish Trail, which became the regular caravan route for the Missouri-Santa Fe-Los Angeles trade. Because of small amounts of snow in the winter, many early immigrants and traders traveled over Cochetopa Pass to reach California, and according to Antoine Leroux, two old trappers, William Pope and Isaac Slover, and eight members of their families, made the first such trip from Taos to the Pacific Coast by wagon in 1837.

In 1842, Marcus Whitman and J. B. Chiles, in two separate journeys, made the return trip from California to Santa Fe, which took them over the same route as that followed by the Slover-Pope party and the Old Spanish Trail through southwestern Colorado.

By the mid-1840s, relations between Mexico and the United States had become strained. The Texas independence question and the need to silence any signs of rebellion in New Mexico and California led to a trade restriction for Americans along the Old Spanish Trail. The imposition of duties further deterred commercial traffic, and with a decreased demand for pelts in New York and London, the day of the trapper and trader in the southwest drew to a close. What the trapper-explorer accomplished, however, cannot be measured merely in a commercial sense, for these unofficial explorers had plotted the courses of the western rivers, discovered the passes through the Rocky Mountains, prepared the way for government explorations, and opened the door for European settlement by breaking down Indian self-sufficiency. The first permanent wedge had been driven into the rugged transmontane west. Although a few mountain man-fur trapper breeds would aid the coming generation of Army explorers in the late 1840s and 1850s, most of what the trapper had learned by hard experience had to be relearned and reinterpreted to suit the needs of a more modern generation. Antoine Leroux, who had repeatedly trapped and explored the present-day Gunnison country, was one of the trappers who would later describe his knowledge to Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri and others seeking information on the best rail route to the Pacific. Leroux later served as a guide on the Gunnison exploration party in 1853, an expedition that would greatly influence the future events of southwest Colorado.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Colorado – The Centennial State

Discovery of the Rocky Mountains

Source: The Bureau of Land Management