By Steven F. Mehls, Bureau of Land Management, 1984

The mountains of northeastern Colorado held vast treasures of silver and gold, and it was here that initial discoveries of those metals were made. While fur trappers used the area’s animal wealth, they did not know about or were not interested in the resources beneath the ground. Some mountain men like James Purcell reported finding gold in streams they trapped. During his 1806 trip, party members found small amounts of placer gold in various river beds. Almost 40 years later, while accompanying John C. Fremont’s expedition, William Gilpin discovered the yellow metal in northeastern Colorado’s creeks. Forty-niners to and from California prospected the region with some success. Colorado reported finding gold in 1853. Five years later, Captain Randolph Marcy’s detachment members panned the mineral from Cherry Creek. Yet, not until the late summer of 1858 did a “rush” start.

Other prospectors were in northeastern Colorado during the summer of 1858. Most famous was William Greene Russell, who led a party of Georgians to the South Platte River that year. Russell had been mining since the 1830s, participating in Georgia’s gold rush and traveling to California during the excitement of 1849.

Russell passed through Colorado on his way west, and after his experiences on the Pacific Coast, he remembered the promising-looking streams of the central Rocky Mountains. During the winter of 1857-1858, Russell formed a party in Georgia to prospect the South Platte River. The following spring, they headed west, passing through Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The group was joined by some Cherokee who had mined gold in Georgia before their removal. The enlarged party moved along the front range, then up the South Platte River to its confluence with Cherry Creek, where prospecting began. Placer gold was discovered after weeks of discouragement at Dry Creek, near present-day Englewood, Colorado.

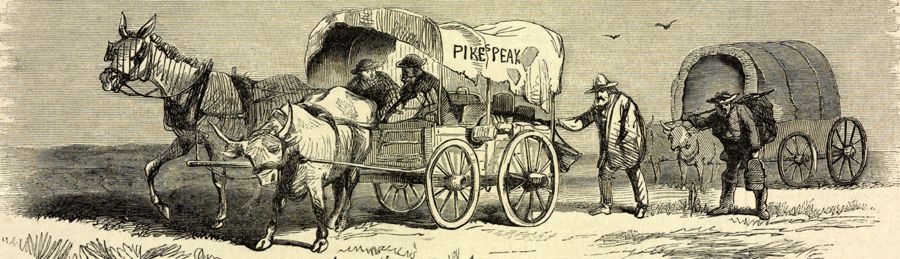

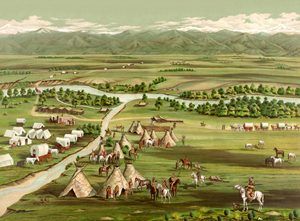

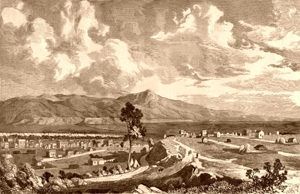

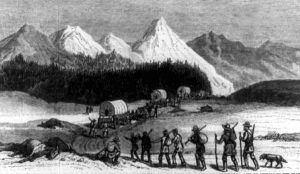

Emigrants arrive in what will soon be Denver, Colorado.

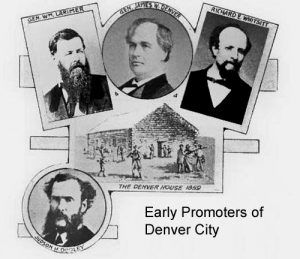

These initial finds were small, but other gold seekers from eastern Kansas joined Russell’s party over the summer. The Lawrence Party arrived only to find deposits along Dry Creek exhausted. However, convinced of the area’s potential, group members stayed on and founded Montana City. The site was not well located, and the party soon moved their “city” to Cherry Creek, renaming it St. Charles. Some group members returned to Kansas to encourage others to join them and file claims. At the same time, Russell and his men established Auraria on the opposite bank of Cherry Creek. As news spread, more people came to the new diggings. General William H. Larimer and his small band of town promoters from Leavenworth, Kansas, were among them. Larimer and his associates arrived in Colorado in November 1858 and founded Denver City on the site of St. Charles, having bought out the St. Charles Town Company. Denver City was named in honor of Kansas Territory’s governor, James Denver.

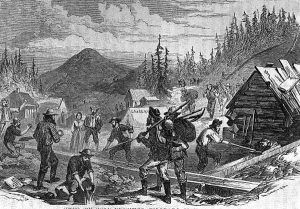

Aside from town promoters, others joined the 1858 movement to Cherry Creek. By the end of 1858, population estimates ranged as high as 2,000 in the new mining camps. It was not until 1859 that a full-scale gold rush finally took place. This time lag, especially between Purcell’s reports and the 1859 stampede, was due to many reasons. By that time, conditions were right for this event. A financial panic in 1857 developed into a full-scale depression by 1858. Frontier areas of the Mississippi Valley were especially hit hard by an economic crisis. To revive their sagging businesses, merchants in the Missouri River towns like Leavenworth, Kansas, or St. Joseph, Missouri, took the news of gold discoveries and embellished it. They then had propaganda circulated throughout the United States. These mercantilists undoubtedly felt they would benefit from an increased outfitting business if a rush occurred since they were close to the mines. Some towns commissioned guidebooks for the miners. These publications stressed quick wealth, the easy trip across the plains, and unbounded opportunities. Of course, each work suggested specific trails and towns as the “only” route west. With shady information available, many men in the Midwest spent the winter of 1858-1859 planning their trips to the Rockies. Most of those who participated in the rush were young men in their late teens or early twenties. They found starting challenging since the Panic of 1857 closed so many opportunities. Further, many sought one “great adventure” before settling into routine farming. The Pike’s Peakers, by and large, were too young to have participated in the Mexican-American War, missing out on that adventuresome opportunity.

Others saw the goldfields, especially after reading the promotional literature, as a way to make a quick fortune and then return to settle down. Along the same lines, some went west because they needed a new start, possibly from a love affair gone awry, debts, or running from the law. Some men came to Colorado to avoid being caught up in increasing sectional tensions between the North and South. For these and other reasons, the “Fifty-Niners” rushed across the plains to the goldfields during the spring of 1859. Possibly 100,000 people flocked to northeastern Colorado as a result of the boom. To encourage immigration, local Denver boosters also started their campaigns. Foremost among these propagandists was William N. Byers, editor of Denver’s first newspaper, the Rocky Mountain News. Not only did he try to entice new miners west, but he also faced the problem of keeping morale high for those already here. By mid-summer 1859, a movement back to the States took place. It was called the “go-backers.” Byers, at first, attempted to stem the tide, and then he rationalized that those leaving were undesirable scum and did not have what it took to build a new empire of the Rockies. Despite Byers and other boosters, many argonauts returned to their homes after finding gold much harder to come by than their guidebooks claimed. As a famous slogan of the day said: “Having seen the Elephant.” One reason for the go-backer movement was the difficulty many pioneers experienced on the trail to Colorado. The Fifty-Niners were hardly the first to travel the region, but gold-seekers did not use the knowledge gained by previous travelers. The Oregon Trail was used extensively since 1840, crossing extreme northeastern Colorado near Old Julesburg. By the 1850s, the Oregon Trail was developed into a national highway, used by thousands to make their way to the Pacific shores. Because of the California gold rush, its name was changed to the Overland Trail. At Old Julesburg, a trail branch turned southwest along the South Platte River, following Major Long’s route of 1820.

This pathway was known as the South Platte Trail. Fifty-Niners extensively used it, and it became one of the primary routes to Colorado during the 1860s. A second, well-established route to the goldfields by 1860 was the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail, which passed through southeastern Colorado along the Arkansas River. At Bent’s Fort, the Santa Fe Trail was joined by the Old Cherokee Trail that ran north, along the front range to the future site of Denver. This route was used by Southerners who came to northeastern Colorado between 1859 and 1860. The Old Cherokee Trail remained a foremost north-south route in the region during the 19th century. Another pathway favored by some was the Smoky Hill Road. It ran west from Leavenworth, Kansas, along an old Army road, and, once in Colorado, it followed the Smoky Hill River from present-day Cheyenne Wells northwest to Denver. In northeast Colorado, this trail had three different routes; the North and south branches took slightly different paths from present-day Limon to Denver. The branches were for access to water and to shorten the trip. The other trail used by hopeful miners was the Republican River Road. It followed the Republican River into northeastern Colorado and westward until reaching the South Platte Trail. The Republican River Route was the region’s least-used route. However, it shared problems that are common to all other trails.

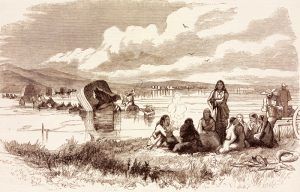

Despite extensive information on high plains travel, the Fifty-Niners and many guidebook authors mostly ignored it. This situation came about from the excitement of the moment and the optimism of many emigrants. However, once on the trail, potential miners found themselves ill-prepared. Often, supplies necessary for survival were left behind or ignored so they could take more mining equipment. All forms of overland transportation were used — wagons, carts, buggies, horses, mules, and on foot. A small band would often assemble at a supply town and embark on the journey without hiring a guide or organizing a wagon train. On the trail, emigrants soon found many problems lying waiting for them. Securing a fuel supply was difficult since few trees grew on the plains. As a substitute, buffalo chips were used when they could be found. Equally crucial and scarce were food and water for both man and beast. Streams and springs with water during spring run-off usually dried up by mid-summer. Without the precious fluid, a party could go for days as water holes dried up from heavy use. Another problem migrants found was a lack of game and forage along the trails. Many travelers took supplies for a few days, counting on living off the land for the rest of the trip. As native food sources were exhausted, the trails grew wider and wider. At points along Smoky Hill Trail, it was as much as 12 miles across as foragers spread out.

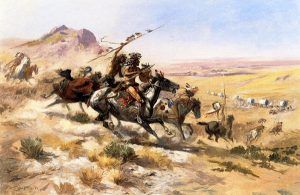

The Fifty-Niners reported numerous acts of cannibalism and discoveries of bodies of those who starved to death along the way. At one time, the Smoky Hill Route was nicknamed the “Starvation Trail” as food supply problems became acute.” The climate presented another challenge for voyagers. Those who traveled too early or late in the season were often caught in blizzards and perished. For those on the trail during the summer, thunderstorms, hail, tornadoes, and flash floods presented potential difficulties. A storm could ruin an outfit, but it also turned many areas, especially along stream banks, into quagmires that could trap a wagon for hours or days. The riverbeds contained hidden pockets of quicksand that could swallow people, animals, or whole wagons. These factors slowed travel; a trip from the Missouri River to Colorado often took over a month. Another obstacle to travel also persisted in northeastern Colorado — Native Americans. The area’s inhabitants, for various reasons, attacked parties on the plains. Usually, their raids were aimed at individuals or small groups that could be easily overwhelmed. During the 1860s, native violence was so great that various trails were closed to travel. By the early 1870s, as railroads inched across the plains, travel became easier and safer. Ten of thousands successfully journeyed to northeastern Colorado despite all the problems.

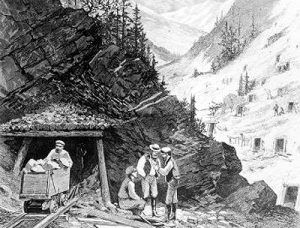

After facing the perils of the eastern flatlands, the new settlers were often disappointed when they reached the Denver area goldfields. More determined to find the precious mineral, others spread out into the mountains, searching for the yellow metal. Their efforts were successful, and strikes were made in 1859 in Gilpin, Clear Creek, and Boulder Counties. More than anything else, these findings slowed the go-backer movement and laid the foundations for Colorado’s development. In January 1859, John H. Gregory, who came to Cherry Creek, turned his attention to Clear Creek. He felt that gold could be found in the mountains to the West. Following Clear Creek to its forks, Gregory turned along North Clear Creek and found promising gravels. When he reached a place soon to be known as Gregory Gulch (Blackhawk–Central City area), he hit pay dirt. News of the find was met with a mixture of skepticism and jubilation. Many felt it was a hoax, but others abandoned Denver City and relocated to Gregory Gulch. The discoveries along North Clear Creek did much to silence criticism about Colorado, but, more importantly, Gregory’s success caused others to prospect in the mountains. Like Gregory, another man who saw the potential of Clear Creek was George A. Jackson, a disgruntled Fifty-Eighter unwilling to give up yet. Jackson followed Clear Creek to its Forks and continued west along the stream. At Chicago Gulch, near present-day Idaho Springs, Jackson found gold. Like Gregory’s earlier discovery, news of Jackson’s work made its way to Denver City, which was highly publicized by local newspapers. With proven strikes as evidence, thousands poured into Clear Creek Canyon during 1859 and 1860. By the mid-1860s, the area was firmly established as the center of Colorado mining.

Simultaneously, Jackson and Gregory made the 1859 strikes; other prospectors were busy north along Boulder Creek. That waterway and its tributaries also held pay dirt in mineable quantities. Soon, Gold Run in Boulder County rivaled Clear Creek for honors as the area’s most significant mining region. Some of the first finds were made near what became Gold Hill and Jamestown. Population growth was so rapid that by 1860, Gold Hill was described as a center of a culture where all the necessities of “civilized” life could be obtained.

Further south, others experienced success, too. Travelers, wearied by crossing the plains, stopped at Fountain Creek along the Old Cherokee Trail and put their picks and pans to use. They encountered small pockets of gold and continued to prospect the area. While mining was ongoing, other capitalists decided to take advantage of “gold fever” by founding a town. They platted the Colorado City Town company, but the diggings played out. The town remained as an outpost of settlement along the trail. Gold seekers also examined the northern mountains. The Cache la Poudre River was prospected with other streams but with minimal results. Boulder and Clear Creeks remained the most prosperous and active of northeastern Colorado’s mining regions. Yet even these locales experienced problems.

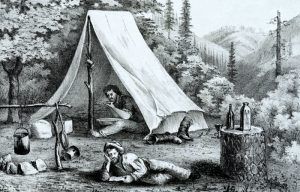

Early Colorado miners expected to repeat the California experience. Whereas a simple pick and pan or sluice box was all that was needed to remove streambeds in California, gold in Colorado was not found as nuggets but rather as “float” gold, that is, particles too small to be recovered by conventional means. The vein (or lode) had to be mined from solid rock to make money in Colorado gold. Hence, underground hard rock mining developed quickly. Stamp mills were brought to Colorado as early as 1860 to crush gold from the rock after it was mined. Another technique, the arrastra, was also tried to pulverize ores. Due to the difficulties and costs, individual prospectors were replaced by capitalists and mining engineers in northeastern Colorado’s mines. As localized placer deposits played out, most miners moved on, and in 1865, ghost towns already dotted the hillsides. However, not all mining camps were abandoned, even those with an exciting, if somewhat short, life. These communities grew quickly at the site of a strike, and because of their presence, Colorado’s mining frontier took on a distinctly urban cast. Towns served many diverse functions and were necessary for miners’ needs. Wrestling gold from the mountains was a full-time job, so those who did it had no time left for other pursuits like agriculture.

To fill this void, merchants moved to the towns. Laundries, boarding houses, restaurants, saloons, and rowdy houses were soon in business. Prices for goods and services were high, and so were wages. During flush times, everyone prospered. Because of their rapid growth and often short lifespan, in addition to a transient population, most of the mining camps were dirty, crowded places that lacked any evidence of planning. The lifestyles of miners were hardly enviable. Work hours were controlled by the sun. The mines’ conditions varied, but they were usually unsafe, wet, cold, and dirty. Miners often had only a tent, a lean-to, or a rudimentary lumber shack for shelter. They were cold in winter, warm in summer, and wet when it rained or snowed. Diets consisted of beans, salt pork, and sourdough bread. Only on rare occasions did fresh meat and fruits or vegetables find their way onto tables. Since mining towns had unpaved streets and no sewers, sanitation was a continual health problem. Women were few in these male-dominated camps, and those who did brave the mountains were usually prostitutes and dancehall girls. Saloons provided an escape from dreary conditions through alcohol while serving as local social centers.

Vigilante Notice.

Law and order were other problems that all miners faced. Crimes like murder and theft had to be dealt with, as did claims protection. Camp residents were outside an effective span of authority and formed their own extra-legal governments. These were known as mining districts. The area’s residents established systems as self-governing through elected officers chosen by a vote of all. These officials dealt with day-to-day problems like registration of claims and collection of fines. Significant decisions on camp policy were made at town meetings. Trials of severe crimes were conducted similarly. Most laws and rules were from the East, but regulations regarding claims had little or no precedent, and miners were forced to make their own as they went. Much of this was based on Spanish tradition used in California ten years earlier. Many of these procedures were incorporated into later modern state and federal laws. In dealing with severe criminal cases, the miners’ courts sought to ensure a fair but speedy trial. Except for especially violent crimes where hanging was called for, the courts usually whipped and banished or just banished the offender because there were no jails. These self-governing units functioned until a territorial administration could be established.

The infant city of Denver shared many of the same problems as other mining camps. From 1858 until 1860, Auraria and Denver City competed to attract settlers and businesses. Finally, in 1860, the rival town companies agreed to merge under the name of Denver. This was partly due to the hardships that both towns faced. They both had transient populations that tended to decrease political stability and when news of the Clear Creek and Boulder County gold strikes was made public, Denver was nearly depopulated. Like mountain camps, Denver was beyond the effective control of Kansas civil authorities, and no town government had yet been established. The town company tried to handle problems like the title to town lots, but the serious crime was beyond their power. By 1860, Denver was gaining a reputation for lawlessness. To stop criminal activity, local business and civic leaders formed vigilance committees. The “vigilantes” had direct methods of dealing with lawbreakers. The offender was notified to mend his ways. If no change occurred, he was usually taken by masked men and summarily executed at night.

Denver business and civic leaders, in 1860, were concerned with more than law and order. They had come west with visions of a prosperous future, as had most miners. After arriving at Cherry Creek, it was decided that Denver should be built into the commercial center of the Rocky Mountain West, much as San Francisco was for the Pacific Coast. In the early sixties, membership in Denver’s society constantly varied because of changes in social circumstances, but goals remained the same. They identified a significant impediment to Denver’s growth was the town’s isolation from the East. Repeated efforts were made to encourage stage and freight companies to extend their lines westward to Denver. Pleas came from the Denver Board of Trade, the business community’s voice. This panel and other boosters were successful enough in their endeavors that by 1864, travelers and journalists who visited the city considered it quite stylish. Local entrepreneurs provided education, the arts, and entertainment for the citizenry by local entrepreneurs. By 1865, social class lines were distinguishable, and a solid core of the elite had established itself. This group guided the town’s destiny well into the 20th century.

One significant need these movers and doers did not overlook was establishing a territorial government for Colorado. They felt they could make their needs known in such an organization. Also, the government would provide effective control of the area by a legally constituted authority, and residents would no longer be forced to depend upon themselves for law and order. Finally, a territorial government for Colorado would unite all mining districts under one administrative unit. Until the creation of Colorado Territory, lands in northeastern Colorado north of the 40th parallel were part of Nebraska Territory, while those South of the line were part of Kansas. In 1858, the area’s residents requested the Federal government’s creation of a separate territory for them almost from the beginning. As with the miners, other northeastern Coloradans realized they were beyond the effective control of Kansas and Nebraska. To fill this void, early settlers established the Territory of Jefferson. It was an extra-legal government not sanctioned by the national capital.

Nevertheless, the Territory of Jefferson’s voters elected a governor, Robert Steele, a legislature, drew up a constitution and set about ruling northeastern Colorado. Jefferson was supported by many of its members because it helped bring stability and order to the region, and it laid long-term foundations for the Colorado Territory. The territory also sent a “delegate” to Congress to carry on the fight for official recognition.

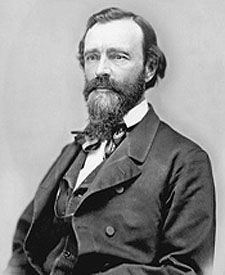

William Gilpin, Colorado Territorial Governor.

Washington, D.C. lawmakers were not ignorant of the situation in the Rockies; however, more pressing problems demanded their attention. By 1859, relations between North and South were so tense that Congress spent most of its time bickering about slavery within the territories and other sectional issues. This kept the legislators from addressing the Colorado problem until early 1861 after most southern states had seceded from the Union. While awaiting Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration as President, Congress found time to act on Colorado’s requests for territorial status. After debates over borders and names in February, the national legislature created the Territory of Colorado while giving it its present boundaries. When news of these developments reached the Rockies, most northeastern Coloradans were pleased to achieve their objective. To preside over this new territory, President Lincoln named William Gilpin, a longtime booster of the West and loyal Republican, to the post of Territorial Governor. Colorado also received a treasurer, marshal, and court system along with this office. Many men filled these posts over the years, accomplishing much for the region, but none faced bigger problems than the first two territorial governors, Gilpin and John Evans.

At about the same time Gilpin arrived in Colorado, the nation was plunged into Civil War. As chief Federal officer, Gilpin was expected to keep the place loyal to Washington and aid the war effort as best he could. To accomplish these tasks, Gilpin asked the legislature and people to remain loyal while simultaneously issuing a call for volunteers to enter Federal service to fight the enemy. Two regiments were raised, and Gilpin issued drafts payable by the U.S. Treasury to supply them. This practice, unapproved by Washington, cost Gilpin his job, but not before hundreds of thousands of dollars in “Gilpin Drafts” circulated around Colorado. The other problem Gilpin, and later John Evans, faced was loyalty. By 1861, many Southerners had relocated to northeastern Colorado’s goldfields. While no longer in the South, they still felt sympathy, and as such, they were seen as potential traitors. Many also felt that the Southern strategy in the West included invading Colorado’s gold regions. Rumors abounded, and there were occasional overt actions, such as raising the “rebel” flag over a Denver business. Gilpin pressed the legislature to enact strict loyalty codes and required an oath of allegiance from public officials and suspected traitors (Southern sympathizers). By 1862 and 1863, these policies had driven the sympathizers underground and away from public displays. This was not hard to accomplish since most of the region’s population could trace its origins and loyalties to the North.

North64, another problem had presented itself to the territorial government—the matter of statehood for Colorado. As with most political questions, there were two sides to this issue. Many, especially groups like the Denver Board of Trade, favored statehood as the ultimate form of political stability and a necessity for continued economic growth within the territory. The opposition feared increased taxes and, in 1864, that a draft to raise troops for the Federal Army would be extended to the new state. Besides local battles over statehood, Colorado’s future became embroiled in national bickering. The Republican party, especially a group of ideologues known as “Radical Republicans,” feared that their new party might be defeated in 1864. When Colorado presented its request for statehood, the Radicals saw its defeat because they thought the new state might vote Democratic. However, the official excuse was that the territory did not have a sufficient population to qualify. Four years later, the situation was somewhat reversed. Radical Republicans now saw that they needed extra votes in Congress, and Colorado could provide them. Again, sides were drawn within the territory.

Despite Colorado forces, the final decision was again made in Washington. This time, President Andrew Johnson refused to sign an enabling act creating the State of Colorado because he realized what his enemies, the Republican Radicals, were doing. From 1868 until 1875, the statehood question lay dormant. Development of the region’s business agriculture, mining, and industries occupied local attention. Nationally, the Republican Party was in complete control. However, by 1875, Colorado’s growth and politics had matured so that a territorial government no longer met Colorado’s needs, and new calls for statehood were issued. In particular, the northeast part of Colorado experienced rapid development during the early 1870s. In 1875, when the statehood question was raised, many residents favored the step, and after considerable debates, a state constitution was submitted to Congress and duly accepted. President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Enabling Act, and on August 1, 1876, Colorado became a full-fledged member of the Union. Colorado relinquished to the Federal Government all claims to lands not already appropriated as part of the normal process. The state’s northeastern section was vital to the success of statehood. The region continued to dominate Colorado’s political and economic life well into the twentieth century. This happened partly because by 1870, the territorial and national governments had removed one obstacle to settlement — the Native Americans.

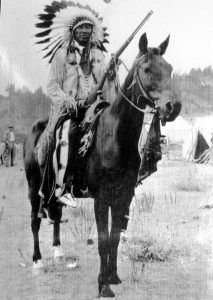

In 1858, when William Russell and other prospectors arrived, the area’s native inhabitants did little to oppose them aside from raiding and killing some of the miners. This mild initial reaction was because most local natives had seen Anglo-Americans come and go in northeastern Colorado for decades. The Native Americans did not realize that thousands of newcomers would stay. Lands along the front range that attracted most Anglo activity were also a no-mans land between the Ute and various Plains Tribes.

By 1861, the situation changed as Native Americans opposed American encroachment. Federal officials began a series of treaty talks with various tribes to reduce the friction. In 1861, negotiators attempted to convince the Plains Tribes to relinquish their title to most of northeastern Colorado and take up reservations along the Arkansas River. This became known as the Treaty of Fort Wise. Two years later, territorial governor John Evans agreed with the Ute, giving them an informal “reservation” west of the front range. In 1865, a final treaty with Arapaho and Cheyenne leaders, the Treaty of Little Arkansas, extinguished the last native claims to northeastern Colorado’s plains. Three years later, Alexander C. Hunt, territorial governor, and Indian Agent, entered into another contract with the Ute that established definite boundaries for their lands west of the Continental Divide. This series of treaties removed nearly all Native American titles in the region. But, the actual reduction of their power proved more complicated.

The natives of northeastern Colorado were dependent upon Euro-American trade by 1859, but since the fur business declined during the 1840s, tribesmen were forced to find new sources of supply. Many immigrants of 1859 and 1860 reported natives along the trails begging for food and metal goods and noted even a few who were starving. They could not satisfy their needs from occasional hand-outs, so many took to raiding small migrant parties and freight wagons along various routes. Horse and cattle herds kept at way stations also became targets for aggression. This pattern continued into 1864. The intensity of raiding increased, as did Anglo-American reactions. The attacks on stage stations and against travelers, especially along the South Platte Trail, were so frequent that during late summer 1864, Denver and the mining camps were cut off from communication with the outside world.

Coloradans organized local militia companies to counter these attacks and prepared to defend their towns. Families who settled at stage stations along the various trails turned their houses into fortresses. The territorial government sent repeated messages to Washington, D.C., for aid in troops and supplies. No response came until 1864 because nearly all available men and materials were used to fight the Civil War. Taking matters into his own hands, Governor John Evans dispatched Major Jacob Downing and the First Colorado Regiment up the South Platte Trail in April 1864. This detachment spent a month searching for hostiles, and finally, on May 2, 1864, they encountered a group of Cheyenne along Cedar Creek. A battle took place in which 26 natives died, 60 were wounded, and Downing’s forces suffered one dead and one wounded. Feeling confident the natives were pacified, the cavalry returned to Denver.

The revenge raids of the Cheyenne soon shattered those optimistic predictions. Throughout the summer, such events continued, and tempers reached their limits in August. That month, the Hungate family, who operated a layover station on the Smoky Hill Road about 20 miles southeast of Denver, was murdered and mutilated. Their bodies were brought to Denver, where the public reaction was a mixture of indignation and panic. Stage and freight drivers refused to cross the plains, and Colorado was isolated from the rest of the United States. Responding to the hysteria, Governor Evans called for “100-day” volunteers to battle the natives. While these new troops, the Third Colorado Volunteers, were mustered into service, General Samuel R. Curtis took 600 men up the South Platte Trail and successfully re-opened that route to the East. Curtis’s efforts eased the crisis but not the mood of settlers in northeastern Colorado.

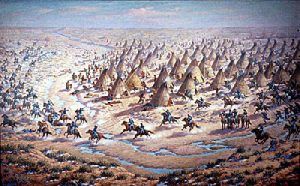

The Colorado Thirds leader, Brevet Colonel John M. Chivington, Methodist bishop of Colorado, had previous military experience fighting Confederates in New Mexico. He also viewed the plains natives as “heathen savages” who were instruments of the devil that should be smitten. Other Euro-Americans widely shared this attitude in 19th-century Colorado. As the Civil War calmed in September and October 1864, many citizens felt the Third Colorado would never see combat. However, their leader planned to gain glory for his troops and end the native problem. As the 100-day enlistments approached expiration in November, Chivington marched his forces southeast out of Denver to find and destroy hostiles. Learning that many Cheyenne and Arapaho, under Chief Black Kettle, had established a winter camp on Sand Creek near Fort Lyon, the Third Colorado proceeded in that direction. Chivington’s scouts reported locating Black Kettle’s village by the end of the month. During the night, troops surrounded the encampment and, at first light, attacked. Men, women, and children all fell before the rifles and sabers. When the battle ended, Chivington’s soldiers committed mutilations and other atrocities that rivaled any the natives had ever done. While this battle occurred just outside northeastern Colorado, its ramifications were felt throughout the region.

The battle of Sand Creek enraged and unified many Plains Tribes into a common desire for revenge. The tribesmen felt betrayed because they had been told to gather at Fort Lyon (near Sand Creek) and were promised safety. Chivington’s actions were seen as duplicity. As soon as the natives could re-group, the war in northeastern Colorado began again. This time, the Sioux opposed the American presence in the area. The first new attacks came in January 1865, when a band of plainsmen raided Old Julesburg. They returned the next month and burned the town. The war spread down the South Platte River as marauding natives attacked stage stations and ranches. Again, travel on the plains became risky, and for a time, during the spring of 1865, trails were closed, this time by the United States Army.

As early as 1863, the Army pondered how best to protect Colorado settlements and the Overland Trail. It was decided that a line of forts along the South Platte (and other trails) would be most effective. From these posts, escorts could be sent with travelers. However, it was not until 1864 that any action was taken. That summer, General Robert B. Mitchell received 1,000 troops to patrol the Platte River Road and establish outposts. At the same time, four sites were located, and forts were built throughout northeastern Colorado. Camp Rankin was built Near Old Julesburg, later renamed Fort Sedgwick.

Further upstream, the South Platte Valley Station near present-day Sterling was taken over for military use. Near the mouth of Bijou Creek, Camp Tyler was established. It was soon renamed Camp Wardell and later Fort Morgan. Instead of using typical wooden stockades, these “citadels” were constructed of sod and adobe. The Army also built Camp (later Fort) Collins on the Cache la Poudre to protect westbound travelers on northern stage roads. Camp Weld, near Denver, was used as a base and supply depot for the regular Army.

A “galvanized Yankee.”

By 1865, as Colorado’s war escalated, the Army established its forts and began filling them with Civil War veterans from both sides. To meet manpower needs, the Federal government started offering Confederate prisoners-of-war freedom in exchange for moving to frontier areas to man Army posts. The ex-Confederates swore an oath of loyalty and entered Federal service. Many were sent to posts in northeastern Colorado. They were nicknamed “Galvanized Yankees,” an allusion to the galvanizing process to stop rust on iron tools. Except for a few days, a year battling natives, life for these soldiers involved garrison and escort duty. Morale was usually low, and alcoholism became a problem. As the Civil War ended, desertions diminished the Army’s effectiveness as drafted soldiers returned home to rebuild their past lives. Nevertheless, the presence of these outposts did make travel and life in northeast Colorado less risky. Many settlers felt the forts represented security, and small communities soon sprang up around them.

During 1866 and 1867, relative calm existed in northeastern Colorado. Sporadic raiding and livestock stealing continued. As more and more Europeans moved into the area, hostile activity increased, especially as the Union Pacific made its way west across Nebraska. Fear of a repeat of Sand Creek, the Army took over responsibility for protecting settlers. In 1867, a new strategy was introduced to quash native activity. Roving patrols were sent to look for hostiles. The government also undertook new treaty talks with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. By this agreement, the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek and the Cheyenne were removed to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) but maintained hunting privileges off the reservation. The Arapaho were sent to the Wind River reservation in Wyoming. To enforce its new strategy that summer, the Army ordered Brevet General George Armstrong Custer and the Seventh U.S. Cavalry to patrol western Kansas, Nebraska, and northeastern Colorado. His quarry was a band of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho led by Chief Roman Nose. Custer found signs of Native American activity, but he never engaged in battle with his foe.

Roman Nose decided, by 1868, that Anglo encroachment had to be stopped. He and his followers increased their attacks on homesteads and small communities in Colorado and western Kansas. To stop Roman Nose, Army officials determined to mount a summer campaign to force the natives onto a reservation. Among the units charged with this task was Major George A. Forsyth’s Volunteer Scouts, a group of 50 frontiersmen who joined the Army to track Native Americans for the summer. By September 1868, Forsyth’s force was on the Arikaree River in northeastern Colorado in hot pursuit of Roman Nose’s band. On September 17, the hostiles ambushed the detachment. The soldiers went to an island in the river and dug in. The battle lasted over a week as 50 men held off an estimated 1,000 warriors. After nine days, help arrived from the Tenth U.S. Cavalry, a black “buffalo” soldiers unit. Amazingly, the volunteers lost only five killed, but many were wounded. Among the dead was Lieutenant Frederick Beecher, for whom both the island and battle were subsequently named. While native casualties were unknown, Roman Nose, the much-feared war chief, died, leading a charge on the embattled soldiers.

The battle accomplished little except to convince the Army of the need for winter campaigns against the Native Americans. The Cheyenne were most vulnerable during winter because of decreased mobility, while their ponies were weak from lack of forage. To lead an expedition into Indian Territory against the natives, General Philip Sheridan chose George A. Custer and his Seventh Cavalry. In November 1868, the Seventh moved from Camp Supply toward reported Cheyenne encampments along the Washita River. Custer pushed his men hard across the snowy plains. In late November, they had reached their objective. Custer repeated Chivington’s strategy and surrounded the camp at night. When the first light dawned, the attack began. Again, Black Kettle was the victim but did not escape this time. As the regimental band played the Seventh’s battle song, “Gerry Owen,” Custer’s troops went about their business of extermination. The Battle of the Washita did much to break Cheyenne’s power, but it was not until the following summer that the last battle for northeastern Colorado was fought.

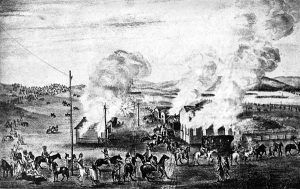

Tall Bull, leading a band of Cheyenne and Sioux, left the reservation in May 1869 and moved north toward their old hunting grounds. Along the way, they skirmished with General Eugene H. Carr’s Fifth U.S. Cavalry in western Kansas. They also raided a Kansas Pacific Railway section station at Fossil Creek. Carr’s troops attempted to stop Tall Bull with little success. However, under increased pressure from the troopers, he was forced to move west into northeastern Colorado to rest. Helping guide the Fifth Cavalry were William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and Major Frank North’s Pawnee Scouts. Finally, on July 11, 1869, the Pawnee Scouts located the hostiles encamped at Summit Springs. Carr decided to attack before his presence was discovered. Using the cover of hillocks and ravines and a fortuitous dust storm, the Army approached within a mile of the camp, sounding the charge before they were discovered. The surprise was complete, and the troops were in camp before the warriors could gather their horses and weapons. The Pawnee, in particular, relished this attack on their old enemies. Tall Bull was dead by the end of that day, and Carr had crushed the last pocket of Native American resistance in northeastern Colorado.

Even before the Battle of Summit Springs, the Army began to lessen its role in the area. A technological revolution occurred, and a “mobile force replaced the older concept of static forts.” As railroads were built across the plains, the Army sought to take advantage of this new agility. No longer would garrisons be necessary every few miles since an entire army could be moved within a few days. Considering this and that most hostilities, by 1868, were outside of northeastern Colorado, the Army started to close its outposts. The closure of forts did not mean the Army completely abandoned northeast Colorado. Detachments occasionally operated in the area. An experimental heliographic signal base was set up on Pike’s Peak, but it proved a failure and was soon closed. By the early 1870s, settlement became so intense in northeastern Colorado that the cavalry went the way of the buffalo into extinction.

Compiled and edited by Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Discovery of the Rocky Mountains

Ghost Towns & Mining Camps of Colorado

Source: Steven F. Mehls, New Empire of the Rockies, Bureau of Land Management, 1984. Note: The article as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been heavily edited.