Pearl de Vere, original photo from Colorado Historical Society, with a touch of color from Dave Alexander.

Pearl de Vere arrived in Cripple Creek, Colorado from Denver during the Silver Panic of 1893. When the country moved to the gold standard, millionaires, including the likes of Horace Tabor, lost their fortunes, and businesses were affected all over the city. This included the many houses of ill-repute.

Pearl de Vere was well known in Denver as Mrs. Martin and had obtained a small fortune from her services to the wealthy gentlemen of Denver. However, when the first slowdown occurred in the city, the wise Ms. Pearl headed to the booming gold camp of Cripple Creek.

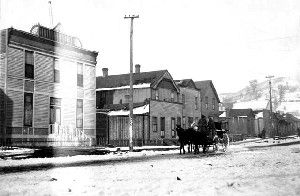

“The Row” Cripple Creek-1893. Courtesy Denver Public Library.

Purchasing a small frame house on Myers Avenue, she opened up for “business” and was an overnight success. Pearl, at 31, was described as red-haired, beautiful, strong-willed, and a smart businesswoman.

Though little is known of her background, historians believe that she was raised near Evansville, Indiana by a good family, who thought that Pearl worked as a dress designer for the wealthy wives of the area.

Catering to the more prosperous gentlemen of Cripple Creek, Pearl’s ladies were the most beautiful of any parlour in the camp, wore fine clothing, received monthly medical exams, and were paid well. And though the “good” women of Cripple Creek shuddered at the thought, Pearl pranced through the camp in a small open carriage, led by a team of fine black horses almost daily. Dressed in a different beautiful costume on every outing, her clothes were the envy of the women and produced the desired effect on the men, as they stared at her with longing.

Bennett Avenue, Cripple Creek, Colorado

Horrified at Pearl’s outings and the fact that Pearl’s ladies dared to shop on Bennett Avenue, the “good” women of the camp complained. Soon, Marshal Wilson regulated the shopping hours of “the girls,” allowing them to visit the stores only during “off hours.” In addition, each “working lady” was required to pay a six-dollar monthly tax, and madams were charged sixteen dollars a month. However, business was brisk and this did little to diminish the popularity of the parlor houses. Meanwhile, Pearl continued her lively forays in her carriage through the streets of the camp. Children were forbidden to walk near Myers Avenue and were made to shield their eyes when Pearl paraded by in her fine carriage.

Soon, Pearl would meet a man named C.B. Flynn, the owner of a small mill. The two married in 1895; however, Pearl continued to run her profitable business. Not long after they were married, a fire raged through the camp, destroying Pearl’s business, Flynn’s mill, and most of the business district of the camp.

The fire ruined Flynn financially and in order to get back on his feet, he accepted a job smelting iron and steel and Monterrey, Mexico. However, Pearl remained in Cripple Creek, intent on rebuilding her business. And rebuild, she did, with the finest parlour house that the city had ever seen. Opening in 1896, the two-story brick building was named “The Old Homestead.” Pearl spared no expense in decorating the opulent parlour, importing wallpaper from Paris, and outfitting it with the finest of hardwood furniture, expensive carpets, crystal electric chandeliers, and leather-topped gaming tables. The house even included a telephone, an intercom system, and two bathrooms, at a time when such things were mostly unheard of.

Four lovely girls joined Pearl in making her house the most whispered about place in town. Drawing a rich clientele from as far away as Denver, references were required of the guests. At $250 a night, when $3 a day was considered a good wage for a miner, only the extremely wealthy could afford to visit The Old Homestead, and reservations were generally required.

Lavish parties were held at The Old Homestead, complete with tropical flowers, and the finest of food and drink. On June 4, 1897, Pearl threw a very extravagant party sponsored by a millionaire admirer from Poverty Gulch. Townspeople watched as cases of French champagne, Russian caviar, and Alabama Wild Turkey were carted into the parlor. Soon arrived two orchestras from Denver. This would be the party to “end all parties.” And, how foretelling that statement would become.

When Pearl appeared she was resplendent in an $800 shell pink chiffon gown, complete with sequins and seed pearls, imported from Paris. During the evening the madam had a bit too much to drink and excused herself, going upstairs to her bedroom. Pearl took some morphine to help her sleep, a common practice at the time.

During the night, one of her girls checked in on Pearl, who was lying in her bed still draped in the chiffon ball gown. Finding her breathing heavily and unable to wake her, a doctor was immediately summoned. But, it was too late and at the age of thirty-six, Pearl De Vere died on that early morning of June 5, 1897.

The coroner stated that Pearl died of an accidental morphine overdose to induce sleep. Most newspapers of the time reported this as a fact; however, at least one insinuated that Pearl had committed suicide. However, most historians dispute this, as Pearl was at her height of success and had no reason to take her life.

Pearl’s body was taken to Fairley Bros. and Lampman undertakers. When Pearl’s relatives were notified, her sister made the long train journey from Indiana. Having believed for years that Pearl was a dressmaker, she was shocked and horrified to find Pearl with dyed red hair and learned of her true vocation. Furious at the undertaker for letting her make the long journey, she left in a huff and refused any responsibility for her sister’s remains.

After Pearl was abandoned by her sister, it was found that she was not the wealthy madam that everyone thought. In fact, her estate did not have enough money to even bury her properly. Pearl’s clientele proposed to auction off the beautiful French gown, but before this could be done a communication was received from Denver containing one thousand dollars and directing that she be buried wearing the lovely pink gown.

Pearl was interred with much pomp and circumstance, the funeral parade being led by the Elks Band, playing the Death March, and escorted by four mounted policemen. Carriages followed filled with businessmen, girls from “The Row,” and many miners from the camp. Pearl’s lavender casket, covered with red and white roses was lowered into her grave at the foot of Mt. Pisgah Cemetery and marked with a wooden marker.

Within just a few short years, Pearl and her grave were forgotten. It wasn’t until the 1930s when Cripple Creek began to promote tourism with Cripple Creek Days, that people again became interested in the story of Pearl De Vere. Her grave had been lost in a weed-filled corner of the cemetery, with her name nearly eroded away from the simple wooden marker.

Soon, a campaign to replace the wooden marker was begun and the Wilhelm Monument Company donated a white marble heart-shaped stone that now rests atop her grave. The original wooden slab marker is now on display at the Cripple Creek District Museum.

The Old Homestead continued to operate until 1917. Later it would serve as a boarding house and a private residence.

In 1957 the owners of the house discovered many original items and wanted to share the house with the public. After extensive renovations, The Old Homestead was opened as a museum in June 1958. Filled with many pieces of original furniture and displays that tell the story of the shady side of Cripple Creek, the house is the only original parlour to survive. Knowledgeable guides tell the story of the house, Pearl De Vere, and Cripple Creek in thirty-minute tours from Memorial Day through October.

Located on Myers Avenue, the hours are 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily in summer, and winter weekends until Christmas.

More Information:

Old Homestead House Museum

353 Myers Avenue

Cripple Creek, Colorado 80813

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated June 2022.

Also See:

Painted Ladies of the Old West

Leading Madames of the Old West

Cripple Creek – World’s Greatest Gold Camp

Cripple Creek Gallery on Facebook

Ghosts of the Cripple Creek Mining District