“If we never see each other again, do the best you can; God will take care of us.”

— Patty Reed of the Donner-Reed Party 1846

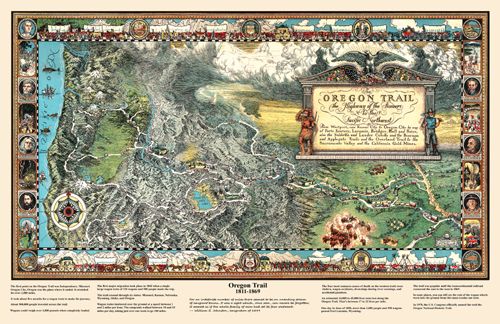

California Trail Map

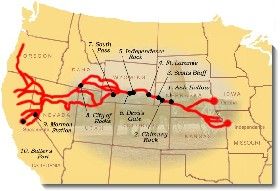

The California Trail carried over 250,000 gold-seekers and farmers to the goldfields and rich farmlands of the Golden State during the 1840s and 1850s, the greatest mass migration in American history. The general route began at various jumping-off points along the Missouri River and stretched to various points in California, Oregon, and the Sierra Nevada. The specific route that emigrants and forty-niners used depended on their starting point in Missouri, their final destination in California, their wagons and livestock conditions, and yearly changes in water and forage along the different routes. The trail passes through Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Oregon, and California.

Before the trail was blazed, the Great Basin region had only been partially explored during the days of Spanish and Mexican rule. However, that changed in 1832 when Benjamin Bonneville, a United States Army officer, requested a leave of absence to pursue an expedition to the West. The expedition was financed by John Jacob Astor, a Hudson’s Bay Company rival. While Bonneville was exploring the Snake River in Wyoming, he sent a party of men under Joseph Walker to explore the Great Salt Lake and find an overland route to California.

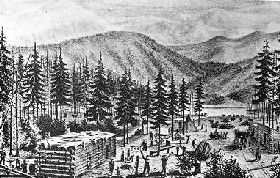

Donner Lake Cabins

Early settlers began using the trail in the 1840s, the first of whom was John Bidwell, who led the 1841 Bidwell-Bartleson Party. In 1842, a member of the Bidwell-Bartleson Party returned to Missouri on the Humboldt River Route.

Among them was a man named Joseph Chiles, who would lead another party to California in 1843 and play an essential part in the subsequent opening of more segments of the California Trail. Throughout the 1840s, settlers would develop shortcuts on the route to California. One such shortcut, the Hastings Route, ran south of the main route. This “new” route would spell the death of many of those in the infamous Donner Party.

The main branch of the trail across the Great Plains generally followed the same path as the Oregon and Mormon Trails but extended to California from various points in southern Wyoming and Idaho. The trail followed the Missouri River before crossing the great plains of Nebraska along the Platte and North Platte Rivers to present-day Wyoming. It followed the Sweetwater River across Wyoming, then northwest along the Snake River to Fort Hall in present-day southeastern Idaho. Fort Hall was the Hudson Bay Company’s post on the Snake River. From here, the primary route followed the Snake River south to American Falls, past Massacre Rocks and Register Rock, to cross the Raft River. After crossing the river, the trail split with the Oregon Trail, with the California-bound emigrants turning south through the Raft River Valley to the City of Rocks.

The trail climbed through the Pinnacle and Granite Passes before dropping down to Goose Creek and meandering south through the northwest corner of Utah and into Nevada. At the headwaters of the Humboldt River in present-day northwestern Nevada, the California Trail followed the north bank of the Humboldt River southwest through present-day Elko, Nevada, and the narrow Carlin Canyon, where, during periods of high water, the route was almost impassable.

West of Carlin, the California Trail climbed Emigrant Pass, descending into Emigrant Canyon to rejoin the Humboldt River at Gravelly Ford. Here, the route divided to follow the north and south sides of the river before rejoining at Humboldt Bar. Various routes branched across the Sierra Nevadas as the emigrants traveled to various destinations in California.

California Trail Ruts

Early emigrants once called the California Trail an elephant due to its difficult journey. In pre-railroad times, getting to California was guaranteed to be an arduous trek. California emigrants faced the most significant challenges of all the pioneer emigrants of the mid-19th century. In addition to the Rockies, these emigrants faced the barren deserts of Nevada and the imposing Sierra Nevada Range.

The travelers of the California Trail often quipped that if you had “seen the elephant,” then you had hit some hard traveling.

When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California, the trickle of emigrants became a flood as thousands of prospectors and families made their way to the Golden State, hoping to find their fortunes. According to some statistics, over 70,000 emigrants used the California Trail in 1849 and 1850 alone.

In the two decades of the 1840s and 1850s, the California Trail carried over 250,000 gold-seekers and farmers to the state’s goldfields and rich farmlands. It was the greatest mass migration in American history.

Eventually, the portions of the railroad followed parts of the California Trail, and as the automobile was introduced and began to be used by the masses, highways replaced the trail. Today, portions of U.S. Highway 50 and Interstate 80 follow the path of the California Trail.

City of Rocks, Idaho

The California Trail system, which now includes approximately 5,665 miles of trails, was developed over the years. Numerous cutoffs and alternate routes were tried along the California Trail to determine the “best” regarding terrain, length, and sufficient water and grass for livestock.

Today, more than 1,000 miles of trail ruts and traces can still be seen in the vast undeveloped lands between Casper, Wyoming, and the West Coast, reminders of the sacrifices, struggles, and triumphs of early American travelers and settlers. About 2,171 miles of this system across public lands, where most of the physical evidence still exists today, is located, including the names of emigrants written with axle grease on the rocks at the City of Rocks National Reserve in southern Idaho. More than 300 historical sites along the trail will eventually be available for public use and interpretation.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2024.

“I think that I may without vanity affirm that I have seen the elephant.”

– Louisa Clapp

Also See: