By Inez Nellie Canfield McFee in 1913

The policy of the American government is to leave their citizens free, neither restraining nor aiding them in their pursuits.

— Thomas Jefferson

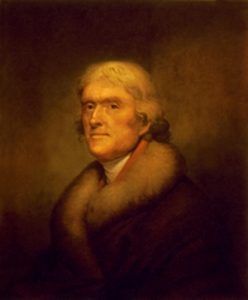

On April 13, 1743, in a farmhouse in Central Virginia mountains, a male child was born destined to stamp his genius and personality upon the future nation. The father was a backwoods surveyor of Welsh origin and a giant in stature and strength. His name was Peter Jefferson, and he called his boy Thomas.

Peter Jefferson owned 30 slaves and a wheat and tobacco farm of nearly 2,000 acres. He was a stern man, though kind and just. One of his favorite sayings was, “Never ask another to do for you what you can do yourself.” He died when Thomas was 14 years old and was always remembered by his son with pride and reverence.

From the very first, young Thomas was an exceptionally bright child. He inherited his mother’s gentle, thoughtful disposition and her love for music and nature. He also took naturally to books and academic pursuits. He might have been over-studious, but his love of nature made him a keen hunter, a fine horseman, and as fond as George Washington of outdoor sports.

There were ten children in the Jefferson home. Young Thomas was the third. He had great affection for his elder sister, Jane. The two were always together, and she did much to elevate and ennoble his character. Her early death, at the age of just 25, was regretted by Jefferson to the end of his long life.

Young Jefferson entered William and Mary College when he was seventeen. He was described as one of the “gawkiest” students of the session, but professors and students alike soon found out his worth. Dr. Small, a Scottish professor of mathematics, was particularly attracted to him and exercised a significant and beneficial influence over his character.

Among Jefferson’s early companions was a cheerful young fellow noted for “mimicry, practical jokes, fiddling, and dancing.” His name, like Jefferson’s, has since been written indelibly upon the country’s history. Every schoolboy and girl knows it. It was Patrick Henry. The two were boon companions in their youthful sports.

Shortly after Jefferson entered college, Patrick Henry strolled into his room one day and delighted him with the news that he had been studying law since they parted and had come to Williamsburg to get a license to practice. Jefferson questioned him eagerly. When he found that the young man had, in reality, studied law for only about six weeks, he was doubtful of the outcome, but young Henry secured his license.

Some time afterward, when Jefferson was himself a law student and young Henry was a member of the House of Burgesses, which met at Williamsburg, matters between the King and the colonies were brought to a straitened pass by the issue of the Stamp Act.

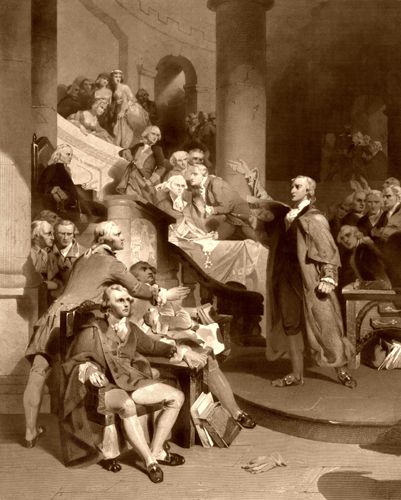

Henry felt it was time to rebel, prepared his famous set of Five Resolutions, and went to the assembly chamber primed for the occasion. It is possible that he gave his young friend, whose guest he was, a hint of what he intended to do. At any rate, young Jefferson watched him intently. Suddenly he saw his friend draw himself to his full height and “sweep with a conqueror’s gaze the entire audience before and about him.” Then, in a voice rich, full, and musical, he poured out his impassioned plea for the people’s liberties. In the midst of it, his voice suddenly rang out in electric tones:

“Caesar had his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third –” He paused. “The house was in an uproar. The Speaker and many of the members were up on their feet shouting, “Treason! Treason!” They thought that he was going to threaten the overthrow of George III, who was King of England and of the colonies. But young Henry did not flinch. He looked the Speaker squarely in the eye and, with a superb gesture, added in a tone that thrilled all hearers, “May profit by their example. If that be treason, make the most of it.”

Young Jefferson never forgot the scene. He listened enthusiastically to the heated debate which followed. The “torrents of sublime eloquence” that fell from Patrick Henry’s lips almost took his breath away, and a well-spring of patriotism bubbled into being in his strong young heart. He resolved that he, too, would strive to serve his country and, to this end, redoubled his academic efforts, sometimes spending 15 hours a day over his books. The result was that he soon became the most accomplished scholar in America. He excelled in mathematics and was acquainted with five languages besides his own.

Monticello

But, first and foremost, Jefferson was a farmer. He once said: “No occupation is so delightful to me as the culture of the earth, and no culture comparable to that of the garden.”

He celebrated the occasion of his coming of age by planting a beautiful avenue of trees near his house, which he had built upon a high hill and given the name “Monticello,” meaning “little mountain.” He delighted in trying new things and imported many trees and shrubs to beautify his grounds, which were marvelous indeed.

We are told that “his interests were wide and intense,” but in nothing, perhaps, did he display a more unfaltering zeal than in the cause of education. In his epitaph, which he wrote himself, Jefferson does not mention his having been Governor of Virginia, Minister to France, Secretary of State, Vice-President, or President of the United States. Instead, there is a modest mention of the three things which he considered had won him his most enduring title to fame, viz.: that he was the “Author of the Declaration of Independence; of the statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and Father of the University of Virginia.”

All of these had freedom at their core. “Free government; free faith; free thought,” says Ellis in his biography — “these were the treasures which Thomas Jefferson bequeathed to his country and his State; and who, it may well be asked, has ever left a nobler legacy to mankind?”

Jefferson was a convention member, which met in Richmond in March 1775 to decide what part Virginia should take in the coming war. He fully endorsed the words of his friend, Henry, when that “Demosthenes of the woods” electrified his hearers with the thrilling cry: “Gentlemen may cry,’ Peace, peace!’ but there is no peace! The war has actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the North will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field. Why stand we here idle? What is it the gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

When George Washington was elected commander-in-chief, Jefferson took the place he vacated in Congress. He was at once recognized as an influential member. No one was better than he on committees. He was so prompt, frank, and decisive. Again, no one had a clearer insight into a situation or understood his countrymen better. He was perceptive, wise, and prudent; by birth, an aristocrat, but, by nature, a democrat. He cared very little for pomp and ceremony and despised titles and the insignia of rank. He could not make a brilliant speech, but the pen waxed mighty in his hand.

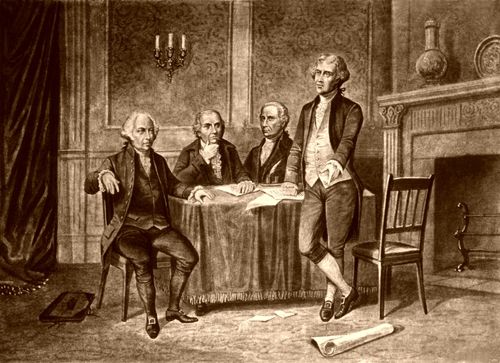

Jefferson is known to fame chiefly because of his authorship of that immortal document, the Declaration of Independence. In June 1776, he was appointed to a committee of five to draw up such a document. The other members were Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. Providence must have decreed that most of the writings should fall to Jefferson, for no one else could have written it so eloquently, so inspiringly. The achievement was dear to his heart, for he directed these lines be carved upon the granite obelisk at his grave: “Here lies buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence.” Glory enough for one man!

On New Year’s Day, 1772, Thomas Jefferson married Mrs. Martha Wayles Skelton, a beautiful, childless young widow. Their life together was a most happy one; Jefferson was an ideal husband and father, and his wife was “one of the truest wives with which any man was ever blessed of heaven.” She died just after the close of the Revolution. Six children were born to them, but only two — Martha and Mary — lived to grow up.

Jefferson looked at life through the lens of a philosopher. Here are ten rules which he considered necessary for a practical life:

1 – Never put off till tomorrow what you can do today.

2 – Never trouble another for what you can do yourself.

3 – Never spend your money before you have it.

4 – Never buy what you do not want, because it is cheap: it will be dear to you.

5 – Pride costs us more than hunger, thirst, or cold.

6 – We never repent of having eaten too little.

7 – Nothing is troublesome that we do willingly.

8 – How much pain has cost us the evils which have never happened!

9 – Take things always by their smooth handle.

10-When angry count ten before you speak; if very angry, a hundred.”

Needless to say that he followed these rules to the letter.

Jefferson was known far and wide for his fairness and justice. He had hosts of friends everywhere, and he entertained them with such lavish hospitality that, in his old age, he was brought to the verge of want and had to mortgage his estate.

Jefferson deplored slavery as a great moral and political evil. He once said: “I tremble for my country when I remember that God is just.” He treated the slaves on his large estate so kindly that they almost worshiped him. It is said that when he returned from his five years absence as Minister to France, his slaves were so overjoyed that they took him from the carriage and carried him into the house, laughing and crying and otherwise expressing their joy because “massa done got home again.”

When George Washington became President, he made Jefferson a member of his cabinet as Secretary of State. Here, he collided with Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury. The two were opposites in many ways and could no more mix than oil and water. It required all of Washington’s tact to keep the peace between them. “Each found the other so intolerable that he wished to resign that he might be freed from meeting him.” At last, Jefferson could stand it no longer. He resigned in January 1794 and returned to his beloved farming at Monticello.

Two years later, he and John Adams were the candidates for the Presidency. Adams received 71 votes and Jefferson 68. As the law then stood, this made him Vice-President. Adams was a Federalist, and Jefferson, a Republican. Therefore, it was not perhaps to be expected that they should agree. Adams, however, did not try. He ignored Jefferson in all political matters. At the next election, Jefferson and Adams were again the presidential candidates, and Jefferson was elected. The quick-tempered Adams was so nettled over the affair that he arose at daybreak, on the day of the inauguration, and set out in his coach for Massachusetts, refusing to wait and see his successor installed in office. In later years, however, he repented of his foolishness. Jefferson and he reconciled and kept up a friendly correspondence to the end of their lives.

As President, Jefferson was much beloved. His inauguration was observed as a national holiday throughout the country. Of course, this was distasteful to Jefferson, who hated pomp and ceremony. A story is on record that he rode to the Capitol on horseback and hitched his horse to the fence while he went in, unattended, to take the oath of office.

Whether it is true or not, we know that during his term of office, Jefferson frowned upon all displays, and would have no honors shown to him that might not have been offered to him as a citizen.

Jefferson chose James Madison, his most intimate friend then, for his Secretary of State. Congenial men made up the remainder of the cabinet. This “happy family” worked together in peace and harmony throughout the two terms of Jefferson’s presidency. Many important national events marked his administration. Chief of them all was the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France, in 1803, for fifteen million dollars. Eleven entire States and parts of four others were later carved from this vast domain.

Jefferson retired forever from public life at the close of his second term. “From that time,” said Daniel Webster,” Mr. Jefferson lived as becomes a wise man. Surrounded by affectionate friends, his ardor in the pursuit of knowledge undiminished; with uncommon health and unbroken spirits, he was able to enjoy largely the rational pleasures of life; and to partake of that public prosperity to which he had contributed so much. His kindness and hospitality; the charm of his conversation; the ease of his manners; and especially the full store of revolutionary incidents he possessed, and which he knew when and how to dispense, rendered his abode attractive in a high degree to his admiring countrymen. His high public and scientific character drew toward him every intelligent and educated traveler from abroad.”

“The Sage of Monticello” died on the afternoon of July 4, 1826. A few hours afterward, John Adams, too, breathed his last. Thus, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the two men who had been the most instrumental in bringing it about passed away. “Their country is their monument; its independence their epitaph.”

By Inez Nellie Canfield McFee, 1913. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

About the Author: This article on Thomas Jefferson was written by Inez Nellie Canfield McFee in 1913 and included in her book American Heroes From History. McFee also authored several other books on American History, poetry, birds, and more. The article as it appears here, however, is not verbatim as it has been edited.

Leaders of the Continental Congress, John Adams, Gouverneur Morris, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson. By Augustus Tholey, 1894

Also See:

Thomas Jefferson – The Father of American History

The Presidential Election of 1800