The notorious trans-Atlantic slave trade, which peaked during the 18th and early 19th centuries, dispersed millions of Africans throughout the Western Hemisphere. The first Africans arrived in colonial North America at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, and scholars contend that British colonists initially recognized them as indentured servants. Their status, however, changed in 1641 when the Massachusetts Bay Colony sanctioned the enslavement of African laborers. Similarly, Maryland and Virginia authorized legal servitude in 1660, and by 1755, all 13 colonies had legally recognized chattel slavery.

Due to diverse climates and geographic conditions, legal bondage varied in colonial North America. In the North, most Africans labored on small farms. Those living in cities worked as personal servants or were hired as domestics and skilled workers. Although northern colonists had little use for slave labor, they accumulated substantial profits from the lucrative slave trading industry. Conversely, southern colonies grew dependent on human bondage. Southern landowners often purchased African laborers for their tobacco, sugar, cotton, rice, and indigo plantations. By the late 18th century, slave labor became increasingly vital to the Southern economy, and the demand for African workers contributed significantly to the steady population increase. This population growth and the threat of insurrections induced colonial legislatures to pass legal codes that restricted the movement of enslaved Africans. While white colonists petitioned for independence from Great Britain, anti-slavery advocates demanded human rights and liberty for all people, including slaves.

Shortly after the American Revolution, calls to abolish slavery and the slave trade generated increasingly widespread support. Led by Quakers and liberated African-Americans, the anti-slavery movement swayed some northern state legislatures to grant immediate release to soldier slaves and gradual emancipation to other enslaved Africans. Northern slaveholders allowed some bondsmen to purchase their freedom, while others petitioned for liberation through the courts. Slavery remained a vital element of southern society; however, any opportunity to eliminate the institution nationwide ended in 1787 when the United States Constitution permitted the slave trade to continue until 1808 and protected involuntary servitude, where it then existed.

The emergence of the cotton gin in 1793 revolutionized cotton production, further solidifying the institution of slavery in the South. “King Cotton” dominated the southern economy, as cotton production rose from approximately 13,000 bales in 1792 to more than 5 million bales by 1860. Increased cotton production necessitated an increase in slaves to work the fields, where men and women often toiled side-by-side. The African-American population in the South also rose from approximately 700,000 in 1790 to nearly 4 million by 1860. By the mid-19th century, the majority of the nation’s cotton was raised in Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, and nowhere in the antebellum South was the cotton economy more dominant than Natchez, Mississippi, which was “…the wealthiest town per capita in the United States…” on the eve of the Civil War.

Slaves in the South’s urban black community frequently worked as domestics or in business establishments. The South’s small segment of free blacks comprised tradesmen and craftsmen, including carpenters, barbers, blacksmiths, dressmakers, and seamstresses. However, free blacks also earned their livings by peddling, fishing, farming, and chopping wood. One of the most notable members of the South’s free black community was William Johnson, a former slave who became a prosperous barber renowned for his business acumen and wealth. Emancipated in 1820 at 11, Johnson was apprenticed to a free black barber. Johnson entered the business in 1828 and was successful enough by the mid-1830s to take advantage of varied business opportunities. He operated three barbershops in Natchez, Mississippi, where he employed free blacks and slaves and owned farmland cultivated by slaves and white overseers.

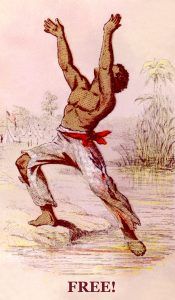

Although masters closely oversaw every aspect of their slaves’ lives, slaves retained some autonomy in their private family lives, relations, and religious practices. Slaves endured the worst aspects of slavery through the strength of their social and cultural ties. A distinctive black culture arose, which provided meaning to life and transmitted values, attitudes, and beliefs throughout the slave community. Yet, the yearning for freedom was ever intense, as James L. Bradley succinctly stated in 1835 in his autobiography:

“From the time I was fourteen years old, I used to think a great deal about freedom. It was my heart’s desire; I could not keep it out of my mind. Many a sleepless night I have spent in tears because I was a slave. My heart ached to feel within me the life of liberty.”

The brutality of slavery and the desire for personal freedom inspired many slaves to rebel against their conditions. Slave rebellions in the South, the most dramatic form of resistance, were few and unsuccessful due to the control slave owners exerted over their slaves. The most prominent slave rebellion in the Lower Delta region occurred near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1811. Four to five hundred slaves, led by the free mulatto Charles Deslondes, sent whites fleeing to New Orleans from the parishes of St. Charles and St. John until a contingent of U.S. Army regulars and militiamen routed the slaves. Over 60 slaves were killed during the rebellion, and those captured were beheaded, with their heads placed atop pikes on the road to New Orleans to warn other would-be rebels.

Slaves more commonly used flight as a form of resistance. Some slaves escaped and took refuge with Indians, often welcoming the runaways as community members. Others fled into unclaimed or secluded territories, such as the bayous of Louisiana, and formed maroon or free societies there. Still, others fled northward or to Mexico and the Caribbean, often receiving food, shelter, and money from a movement collectively known as the “Underground Railroad.” Operating without formal organization, “conductors” of Underground Railroad stops, such as the Epps House in Bunkie, Louisiana. The Jacob Burkle and Hunt-Phelan homes in Memphis, Tennessee, included both white and black abolitionists, one of which was Harriet Tubman, enslaved African-Americans, Indians, and members of such religious groups as the Quakers, Methodists, and Baptists.

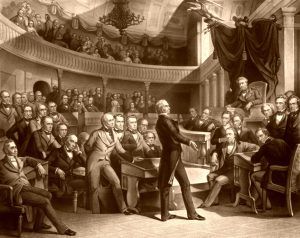

In the middle of the 19th century, the United States Congress attempted to reconcile sectional differences by passing the Compromise of 1850, which included a Fugitive Slave Law. In addition to legislating the return of runaway slaves, the act proclaimed that federal and state officials and private citizens must assist in their capture. As a result, northern states were no longer considered safe havens for runaways, and the law even jeopardized the status of freedmen.

By the end of the decade, slavery had polarized the nation even further, as events such as the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852), the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, the Supreme Court decision in the Dred Scott Case in 1857, and the failed Harper’s Ferry insurrection led by John Brown in 1859 eventually precipitated the nation’s Civil War.

While the Civil War captured the country’s attention, thousands of once-enslaved African Americans deserted southern plantations and cities and took refuge behind Union lines. With the assistance of more than 180,000 African American soldiers and spies, the Union secured victory over the Confederacy in 1865. In the aftermath of the war, the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution liberated more than 4 million African Americans.

Following the abolition of slavery, many of the South’s newly freed African Americans sought work in textile and tobacco factories, iron mills, and other industrial enterprises. They were often prohibited from working as artisans, mechanics, and other capacities where they competed with white labor. Others undertook sharecropping, striving to own the land they farmed. Sharecropping gradually stabilized labor relations in the cash-poor South after the Civil War; however, sharecropping also preserved a semblance of the plantation system and its associated patterns of antebellum agriculture. Under sharecropping, the land was divided into many small holdings, giving the illusion of small independent farms. But, many small holdings together actually comprised single plantations, which, through foreclosures, gradually fell into the hands of creditors, who were white. Over the succeeding half-century, a new class of large landowners replaced the old planter caste.

What limited political and social gains African-Americans experienced during Reconstruction (1865-1877) were quickly overturned during the succeeding decades. Every Supreme Court decision affecting African Americans before the turn of the century furthered white supremacy. For example, the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 nullified the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and the court’s later separate but equal verdict, rendered in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, legitimized the “Jim Crow” era of segregation in the South. The Plessv decision upheld the constitutionality of a Louisiana statute requiring African Americans and whites to ride in separate railroad cars. Still, it was soon zealously applied to public facilities of all kinds and entire city blocks of housing. However, the equality of separate African-American facilities was, more often than not, questionable.

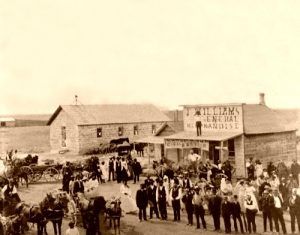

One response to such political, economic, and social oppression was emigration. Though some African Americans were drawn to the African re-colonization movement, far more opted for the western and northern regions of the United States. In 1879, over 20,000 African-Americans migrated from southern states to Kansas and other plains states. These “Exodusters” farmed homestead lands and founded several small communities. Decades later, thousands of the region’s African-American males served in the nation’s armed forces during World War I, prompting a second great migration after the war, as African-Americans moved northward seeking opportunity in the significant commercial and industrial centers of Chicago, Detroit, New York City, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. A similar migration occurred after World War II.

In the 1930s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began focusing the nation’s attention on the status of African Americans under the law, addressing the inherent inequality of separate facilities and attacking the idea of segregation itself. In addition, in 1934, a group of white and African-American sharecroppers organized the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in Marked Tree, Arkansas.

The landowners responded with terrorism, and union members were flogged, jailed, shot, and some were killed. The wife of a sharecropper from Marked Tree wrote:

“We Garded our House and been on the scout until we are Ware out, and Havenent any law to looks to, thay and the Land Lords hast all turned to nite Riding… thay shat up some House and have Threten our Union and won’t let us Meet at the Hall at all.”

The Southern Tenant Farmers Union persevered, however, moving their union headquarters to Memphis, Tennessee. With a peak membership of 30,000, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union was the nation’s first and largest interracial trade union. In addition to staging a successful cotton strike in 1936, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union maintained refuges for tenant farmers evicted for striking. The union also organized a Providence Farm farming cooperative in Homes County, Mississippi. It later opened a second cooperative, the Hillhouse Farm, in nearby Coahoma County, where the first use of a mechanical cotton picker occurred. Later, some Southern Tenant Farmers Union’s organizing skills benefited the civil rights movement.

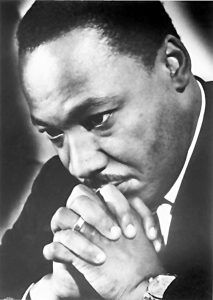

The 1955 lynching of a 14-year-old African-American youth, Emmett Till, in Money, Mississippi, focused national attention on the virulent racism of the South. In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s momentous decision ordering the end of public school segregation, Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954), President Dwight G. Eisenhower — who had initially urged caution in implementing the Brown decision because he did not believe the hearts of men could be changed by law — sent federal troops to Little Rock, focused national attention upon the virulent racism of the South. In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s momentous decision ordering the end of public school segregation, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1954, President Dwight G. Eisenhower — who had initially urged caution in implementing the Brown decision because he did not believe the hearts of men could be changed by law — sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas in the fall of 1957 to ensure the safety of nine African-American children enrolled at Central High School. In 1957 and 1960, Congress passed the first federal civil rights acts in nearly a century, rekindling a federal commitment to the African-American’s right to vote. A few years later, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the president and co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, observed that “…the law may not change the heart, but it can restrain the heartless”.

The life’s work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Birmingham, Alabama; Atlanta, Georgia; and other racial hotspots during the 1950s and 1960s inspired African-Americans throughout the nation as civil rights dominated the nation’s domestic agenda during the early 1960s. President John F. Kennedy sent troops to the University of Mississippi in the fall of 1962 to protect an African-American student, James Meredith, whom a Federal court order had enrolled. The August 28, 1963, march on Washington D.C. brought approximately 250,000 demonstrators to the nation’s capital, again focusing the nation’s attention on the issue of racial inequality in America.

The increasing tempo of far-reaching change continued during the presidential administration of Lyndon B. Johnson. In June 1964, the Supreme Court, in a decision many believed to be of equal importance with the school desegregation ruling ten years earlier, declared that both houses of state legislatures must be apportioned on a population basis to ensure that citizens are accorded the constitutional guarantee of equal protection under the law, ending the rural domination of many state Senates.

Less than a month later, on July 2, 1964, President Johnson signed the most comprehensive civil rights act in the nation’s history. The new act enlarged federal power to protect voting rights, provide open access to public facilities, sue to end lagging school desegregation, and ensure equal job opportunities in businesses and unions with more than 25 persons. In promoting the Civil Rights Act in his first State of the Union message earlier in the year, President Johnson said, “Unfortunately, many Americans live on the outskirts of hope, some because of their poverty and some because of their color, and all too many because of both.” To lift such people’s hopes, President Johnson proposed declaring a “…war on poverty in America.” Congress endorsed the war in August 1964 by appropriating nearly $1 billion for ten antipoverty programs, such as a Job Corps to train underprivileged youths, a work training program to employ them, an adult education program, and a domestic peace corps, all to be administered by the newly created Office of Economic Opportunity.

Resistance to the gains in civil rights for African Americans was formidable. In defiance of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, force and intimidation dating from the previous century sustained the system of racial segregation until the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s. In 1866, race riots erupted in Memphis, Tennessee, and Vicksburg, Mississippi. On July 30 of the same year, over 40 African-American delegates were killed in New Orleans during a meeting at the Mechanic Institute Building to reconvene the state’s constitutional convention. In 1873, over 300 African-Americans were killed by white supremacists in Grant Parish, Louisiana, resulting from a disputed election in what has been called “…the worst incident of mass racial violence in the Reconstruction period.

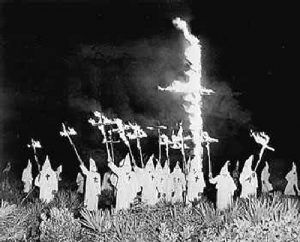

The Ku Klux Klan, which was founded by former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forest in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1866, and other similar groups, such as the Knights of the White Camelia and the Boys of 76, roamed the countryside, hooded or otherwise, terrorizing African-Americans and their supporters in the name of white supremacy. Over succeeding decades, the Ku Klux Klan underwent sporadic surges of popularity, as during the 1920s, the organization added anti-immigrant and anti-Semitism to its litany of hate. In 1954, the Ku Klux Klan re-emerged, more determined than ever to stop integration, following the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown decision, which also spurred the formation of White Citizen Councils throughout the South. The first meeting of a White Citizens Council, whose members considered themselves more respectable than those of the Ku Klux Klan but were just as adamantly opposed to integration, occurred in Indianola, Mississippi, in July 1954. Byron De La Beckwith, who assassinated civil rights leader Medger Evers in Jackson, Mississippi, in June 1963, was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and a White Citizens Council.

The murders of three civil rights volunteer workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in June 1964 increased public support for the growing racial equality movement. Such tragedies also strengthened the resolve of African Americans in their quest for racial equality, as civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael noted:

“They killed them, but they can’t kill the summer and what we’re doing to do this summer. They can’t kill our spirit, only our bodies. They’ll discover what they did when they murdered our people, our brothers. They’ll find that they made us strong, that we’ll beat them sooner because of what they’ve done. The whole nation will rally round — but even more important, we’ll rally round.”

Other examples further set the tone of the tumultuous 1960s civil rights struggles. In 1964, Fannie Lou Hamer of Ruleville, Mississippi, drew national attention for her civil rights organizer work and futile attempts to seat the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegates at the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination convention in Atlantic City. Throughout the summer of the same year, Freedom Schools, staffed by northerners, enrolled thousands of young African Americans and voter registration drives during the summer, known as Freedom Summer. They brought many disfranchised African Americans to the ballot box for the first time. A Mississippi sheriff objected to the presence of civil rights workers from the North, whom he looked upon as busybodies and interlopers, declaring: “Ninety-five percent of our blacks are happy.” In response, some 20 rural African-Americans in his county wrote or dictated letters indicating grievances. One wrote:

“In our schools, we don’t have the books the whites have. We can’t get to learn anything. The colored people is afraid to tell you all we is not happy because we’re scared of losing the jobs we have. When we go to the gas stations, we don’t have any bathrooms. We’re glad that the white people are coming down from the North and that they are thinking of our welfare. We work 12 hours a day and only get $3 pay. Sure, we’re inferior. The white folks over us every way.”

The failure of many Southern states to enforce the voter registration provisions of the Civil Rights Act resulted in an upsweep of civil rights demonstrations, one of the most notable occurred in Alabama. In February 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. and over 700 other African Americans were arrested in Selma. A month later, Alabama state troopers frustrated an attempted civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital. On March 20, President Lyndon Johnson ordered the Alabama National Guard to protect the marchers after Governor George Wallace refused to protect them. A procession of approximately 25,000 African Americans and whites from all over the country began.

In response, Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act, signed by President Johnson on August 6, 1965, which suspended all voter registration literacy tests. In addition, the act empowered federal examiners to register all who qualified by age, residence, and objective educational requirements. The act also authorized the Attorney General to file suits testing the constitutionality of poll taxes in states where it survived. In April 1966, the last poll tax in Mississippi was overturned. The civil rights movement thus came into full bloom in the 1960s. However, as recently as 1973, African-Americans worked and marched to bring racially based injustices to an end in Cairo, Illinois, chronicled by Preston Ewing, Jr., in his book Let My People Go (1996), and continue to strive for racial equality today.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See:

African American History in the United States

The Emancipation Proclamation & the 13th Amendment

Slavery – Cause and Catalyst of the Civil War

Source: National Park Service