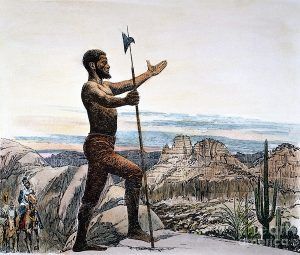

Estevanico came to America with the Spaniards and was probably the first African in the United States.

Slavery in the United States was the legal institution of the enslavement of Africans that occurred from the time of European exploration of North America until the Civil War ended in 1865.

The first Africans in the New World arrived with Spanish and Portuguese explorers and settlers and assisted in the early exploration of the Americas. In 1508, the first enslavement occurred in what would later become part of the United States when Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon established a settlement near present-day San Juan, Puerto Rico, and enslaved the indigenous Taino people. However, by 1513, the Taino population dwindled, and the first African slaves were imported to Puerto Rico.

Later, some black explorers settled in the Mississippi Valley and in the areas that became South Carolina and New Mexico. The most celebrated black explorer of the Americas was Estéban, who traveled through the Southwest in the 1530s.

In 1581, the Spanish in St. Augustine, Florida, imported the first enslaved Africans into the Continental United States. Soon, St. Augustine would become a hub of the slave trade. In 1619, 20 African captives were sold to settlers at Point Comfort, today’s Fort Monroe, in Hampton, Virginia, 30 miles downstream from Jamestown, Virginia. After several years, the colonists treated these captives as indentured servants and released them. However, this practice was gradually replaced by the system of race-based slavery used in the Caribbean. Soon, more African captives were brought to America in increasing numbers to fill the desire for labor in a country where land was plentiful and labor was scarce.

The demands of European consumers for New World crops and goods helped fuel the slave trade. Following a triangular route between Africa, the Caribbean, North America, and Europe, slave traders from Holland, Portugal, France, and England delivered Africans in exchange for colonial rum, sugar, and tobacco. Eventually, the trading route also distributed Virginia tobacco, New England rum, and indigo and rice crops from South Carolina and Georgia.

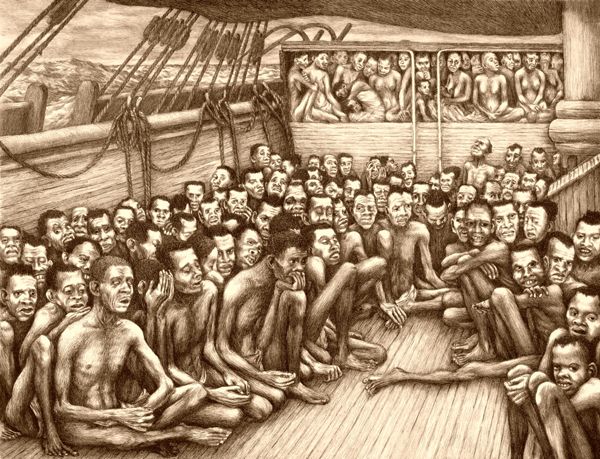

Over the next centuries, ships transported millions of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas. Most of these people were captured in African wars or raids in western and central Africa and transported in the Atlantic slave trade. The capture and transportation of Africans was a horrific experience and often lethal. Two captives died on the march to the Atlantic seacoast, where they were sold to European slavers. Before they boarded the ships, they were separated from family members, segregated by gender, and chained below decks in coffin-sized racks. Due to the lack of basic hygiene, malnourishment, and dehydration, diseases spread wildly. The women on the ships often endured rape by the crewmen. An estimated one-third of these unfortunate individuals died at sea. It took about six months from their capture in Africa to their arrival in America.

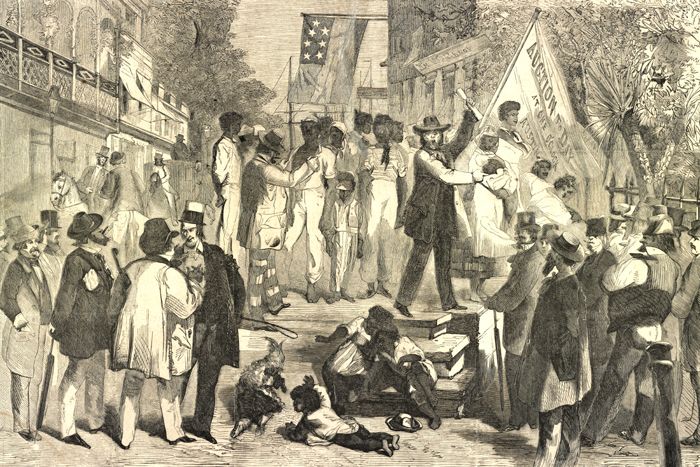

Upon arrival, they were auctioned to owners, who wanted them primarily as plantation workers. Though they came with varied customs, religious beliefs, and language, European standards and ideals were forced upon them once they arrived.

Despite the hardships, slaves managed to develop a strong cultural identity. A strong family and community life helped sustain African Americans in slavery. People often chose their partners, lived under the same roof, raised children, and protected each other. Introduced to Christianity, they developed their forms of worship.

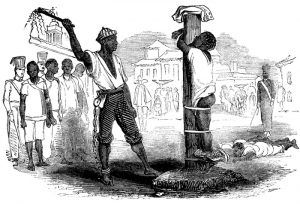

However, brutal treatment at the hands of slaveholders threatened black family life. Slave owners could punish slaves harshly, and enslaved women experienced sexual exploitation at the hands of slaveholders and overseers. They lived constantly, fearing being sold away from their loved ones, with no chance of a reunion. Historians estimate that most slaves were sold at least once in their lives. No event was more traumatic in enslaved individuals’ lives than forcible separation from their families. People sometimes fled when they heard of an impending sale.

Massachusetts was the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641. Attempts to hold black servants beyond the typical term of indenture culminated in the legal establishment of black chattel slavery in Virginia in 1661 and all the English colonies by 1750. Other colonies followed suit by passing laws that passed slavery on to the children of slaves and making non-Christian imported servants slaves for life. This principle prevailed in the English colonies even though they would later win their independence and articulated national ideals opposing slavery.

However, some blacks gained freedom, property, and access to American society. Many moved to the North, where slavery, although still legal, was less of a presence. By 1790, slave and free blacks numbered almost 760,000 and made up nearly one-fifth of the United States population.

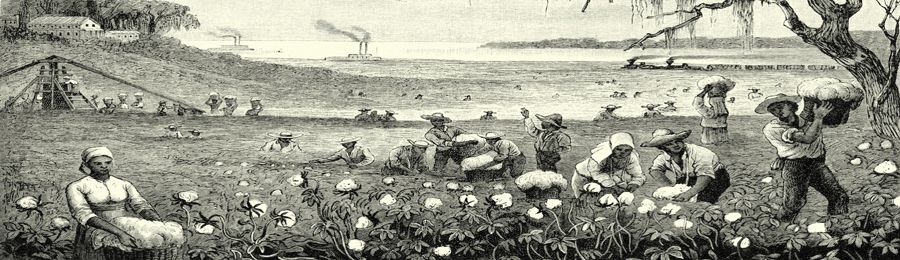

During the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved African Americans in the Upper South mostly raised tobacco. They harvested indigo for dye in coastal South Carolina and Georgia and grew rice using African agricultural expertise. By 1800, rice, sugar, and cotton became the South’s leading cash crops. The patenting of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793 made it possible for workers to separate the seeds from the fiber. Able to process some 600-700 pounds daily, it was ten times more cotton than could be processed by hand.

To meet the growing demands of sugar and cotton, slaveholders developed an active domestic slave trade to move surplus workers to the Deep South. New Orleans, Louisiana, became the largest slave market, followed by Richmond, Virginia; Natchez, Mississippi; and Charleston, South Carolina.

Even though slavery existed throughout the original 13 colonies, nearly all the northern states, inspired by American independence, abolished slavery by 1804. As a matter of conscience, some southern slaveholders also freed their slaves or permitted them to purchase their freedom. Until the early 1800s, many southern states allowed these manumissions legally. Although the Federal Government outlawed the overseas slave trade in 1808, the southern enslaved African-American population continued to grow.

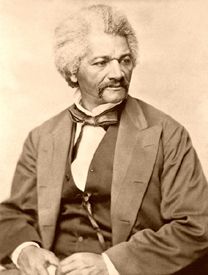

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery and escaped to spend his life fighting for justice and equality for all people.

By the early 1800s, many whites and free blacks in Northern states began to call for the abolition of slavery. Frederick Douglass, a young black slave taught to read by his master’s wife in Baltimore, Maryland, escaped to Massachusetts in 1838. He became an influential writer, editor, and lecturer for the growing abolitionist movement. /bt 1840, abolitionists in Britain and the United States developed large, complex propaganda campaigns against slavery. As the nation split between Southern slave and Northern free states before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad spirited thousands of escaped slaves from the South to the North.

Between 1820 and 1860, more than 60 percent of the Upper South’s enslaved population was “sold South.” Covering 25 to 30 miles daily on foot, men, women, and children marched south in large groups called coffles. One former slave named Charles Ball remembered that slave traders bound the women together with rope. They fastened the men with chains around their necks and then handcuffed them in pairs. The traders removed the restraints when the coffle neared the market.

The Industrial Revolution, centered in Great Britain, quadrupled the demand for cotton, which soon became America’s leading export. Southern planters’ acute need for more cotton workers helped expand southern slavery. When the Civil War began, the South exported more than a million tons of cotton annually to Great Britain and the North textile manufacturers. Short-staple, or upland cotton, dominated the market. An area still called the Black Belt, which stretched across Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, grew some 80% of the nation’s crop. Simultaneously, cotton expanded into the new states of Arkansas and Texas. Enslaved African Americans made up more than three-fourths of the total population in parts of the Black Belt.

By 1860, some four million enslaved African Americans lived throughout the South. Most enslaved people were agricultural laborers on small farms or large plantations. They toiled literally from sunrise to sunset in the fields or other jobs, such as refining sugar. Some slaves held specialized jobs as artisans, skilled laborers, or factory workers. A smaller number worked as cooks, butlers, or maids.

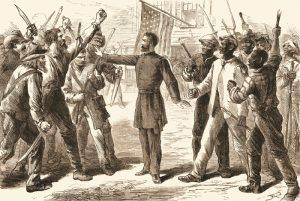

When the Civil War began, many Northern free blacks and runaway slaves from the South volunteered to fight for the Union, hoping to liberate their people across the nation. When President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, it changed the status of three million African Americans in the South from “slave” to “free.” This drastically increased the number of runaway slaves, many of whom joined the Union forces. By the time the war ended in 1865, about 200,000 black men had served as U.S. Army and Navy soldiers. Forty thousand black soldiers died in the war: 10,000 in battle and 30,000 from illness or infection.

On June 19, 1865, the last of the slaves in the U.S. were told they were free by Union General Gordon Granger at Galveston, Texas. The day, now called Juneteenth, or Freedom Day and Liberation Day, has been celebrated by black Americans since 1866, with Texas declaring it a state holiday in 1980 and most of the 50 states since. In June 2021, Congress made June 19 a Federal Holiday through an overwhelming bipartisan vote.

After the Union’s victory over the Confederacy, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 made African Americans full U.S. citizens, and Reconstruction in the South toward equal rights for African Americans. However, it would take over a century for African Americans to achieve equality.

Today’s African Americans, one of the largest ethnic groups in the United States, are primarily the descendants of slaves.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See:

African American History in the United States

African-Americans – From Slavery to Equality

Sources:

Constitutional Rights Foundation

Scholastic

Wikipedia – African Americans

Wikipedia – Slavery