Environmental issues in the European Union

Environmental issues in the European Union include the environmental issues identified by the European Union as well as its constituent states. The European Union has several federal bodies which create policy and practice across the constituent states.

Issues

[edit]Air pollution

[edit]A report from the European Environment Agency shows that road transport remains Europe's single largest air polluter.[1]

National Emission Ceilings (NEC) for certain atmospheric pollutants are regulated by NECD Directive 2001/81/EC (NECD).[2] As part of the preparatory work associated with the revision of the NECD, the European Commission is assisted by the NECPI working group (National Emission Ceilings – Policy Instruments).[3]

Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe (the new Air Quality Directive) has entered into force on 11 June 2008.[4]

Individual citizens can force their local councils to tackle air pollution, following an important ruling in July 2009 from the European Court of Justice (ECJ). The EU's court was asked to judge the case of a resident of Munich, Dieter Janecek, who said that under the 1996 EU Air Quality Directive (Council Directive 96/62/EC of 27 September 1996 on ambient air quality assessment and management [5]) the Munich authorities were obliged to take action to stop pollution exceeding specified targets. Janecek then took his case to the ECJ, whose judges said European citizens are entitled to demand air quality action plans from local authorities in situations where there is a risk that EU limits will be overshot.[1]

Legislation

[edit]Since the late 1970s, the European Union's (EU) policy has been to develop and drive appropriate measures to improve air quality throughout the EU. The control of emissions from mobile sources, improving fuel quality and promoting and integrating environmental protection requirements into the transport and energy sector are part of these aims.

The main advising agency of the EU is the European Environment Agency (EEA). It came into force in 1993, after the decision to locate the EEA in Copenhagen. Work started in earnest in 1994. The EEA's mandate is to help the community and member countries make informed decisions about improving the environment and integrating environmental considerations into economic policies and to coordinate the European environment information and observation network (Eionet). Eionet is a partnership network across member states involving approximately 1000 experts and more than 350 national institutions. The network supports the collection and organization of data and the development and dissemination of information concerning Europe's environment.Climate change

[edit]

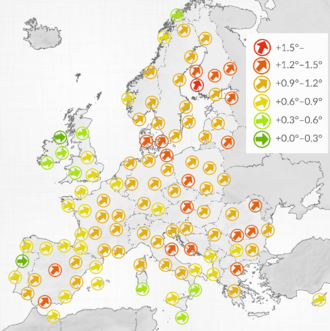

Impacts on European countries include warmer weather and increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather such as heat waves, bringing health risks and impacts on ecosystems. European countries are major contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions, although the European Union and governments of several countries have outlined plans to implement climate change mitigation and an energy transition in the 21st century, the European Green Deal being one of these. The European Union commissioner of climate action is Frans Timmermans since 1 December 2019.[10]

Public opinion in Europe shows concern about climate change; in the European Investment Bank's Climate Survey of 2020, 90% of Europeans believe their children will experience the effects of climate change in their daily lives.[11] Climate change activism and businesses shifting their practices has taken place in Europe.Protected areas

[edit]Protected areas of the European Union are areas which need and/or receive special protection because of their environmental, cultural or historical value to the member states of the European Union.

Policy

[edit]

"Over the past decades the European Union has put in place a broad range of environmental legislation. As a result, air, water and soil pollution has significantly been reduced. Chemicals legislation has been modernised and the use of many toxic or hazardous substances has been restricted. Today, EU citizens enjoy some of the best water quality in the world" (European Commission, EAP 2020[15])

Renewable energy

[edit]

| 10–20% 20–30% | 30–40% 40–50% | 50–60% >60% |

This article needs to be updated. (February 2024) |

Renewable energy progress in the European Union (EU) is driven by the European Commission's 2023 revision of the Renewable Energy Directive, which raises the EU's binding renewable energy target for 2030 to at least 42.5%, up from the previous target of 32%.[16] Effective since November 20, 2023, across all EU countries, this directive aligns with broader climate objectives, including reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 and achieving climate neutrality by 2050. Additionally, the Energy 2020 strategy exceeded its goals, with the EU achieving a 22.1% share of renewable energy in 2020, surpassing the 20% target.[16]

The main source of renewable energy in 2019 was biomass (57.4% of gross energy consumption).[17] In particular, wood is the leading source of renewable energy in Europe, far ahead of solar and wind.[18] In 2020, renewables provided 23.1% of gross energy consumption in heating and cooling. In electricity, renewables accounted for 37.5% of gross energy consumption, led by wind (36%) and hydro-power (33%), followed by solar (14%), solid biofuels (8%) and other renewable sources (8%). In transport, the share of renewable energy used reached 10.2%.[19] Renewable electricity generation reached 50% of total EU electricity in the first half of 2024.[20]

In 2022, Sweden led among EU nations, with nearly two-thirds (66.0%) of its gross final energy consumption derived from renewable sources, followed by Finland (47.9%), Latvia (43.3%), Denmark (41.6%), and Estonia (38.5%). Conversely, the EU members reporting the lowest renewable energy proportions included Ireland (13.1%), Malta (13.4%), Belgium (13.8%), and Luxembourg (14.4%), with 17 out of the 27 falling below the EU average of 23.0%.[21]

The renewable energy directive enacted in 2009 lays out a framework for individual member states to share the overall EU-wide 20% renewable energy target for 2020.[22] Promoting the use of renewable energy sources is important both to the reduction of the EU's energy dependence and in meeting targets to combat global warming. The directive sets targets for each individual member state taking into account the different starting points and potentials.[22] Targets for renewable energy use by 2020 among different member states varied from 10% to 49%.[22] 26 EU member states met their national 2020 targets. The sole exception was France, which had aimed for 23% but only reached 19.1%. By 2022, Austria, Ireland, and Slovenia had dropped below their 2020 targets.[23]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

European Green Deal

[edit]The European Green Deal, approved in 2020, is a set of policy initiatives by the European Commission with the overarching aim of making the European Union (EU) climate neutral in 2050.[25][26] The plan is to review each existing law on its climate merits, and also introduce new legislation on the circular economy (CE), building renovation, biodiversity, farming and innovation.[26]

The president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, stated that the European Green Deal would be Europe's "man on the moon moment".[26] On 13 December 2019, the European Council decided to press ahead with the plan, with an opt-out for Poland.[27] On 15 January 2020, the European Parliament voted to support the deal as well, with requests for higher ambition.[28] A year later, the European Climate Law was passed, which legislated that greenhouse gas emissions should be 55% lower in 2030 compared to 1990. The Fit for 55 package is a large set of proposed legislation detailing how the European Union plans to reach this target.[29]

The European Commission's climate change strategy, launched in 2020, is focused on a promise to make Europe a net-zero emitter of greenhouse gases by 2050 and to demonstrate that economies will develop without increasing resource usage. However, the Green Deal has measures to ensure that nations that are already reliant on fossil fuels are not left behind in the transition to renewable energy.[30][31][32] The green transition is a top priority for Europe. The EU Member States want to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels, and become climate neutral by 2050.[33][34][35][36]

Von der Leyen appointed Frans Timmermans as Executive Vice President of the European Commission for the European Green Deal in 2019. He was succeeded by Maroš Šefčovič in 2023.[37]Environments or ecosystems

[edit]The Nature Restoration Law is a regulation of the European Union to protect the EU environments and restore its nature to a good ecological state through renaturation. The law is a core element of the European Green Deal and the EU Biodiversity Strategy and makes the targets set therein for the "restoration of nature" binding.[38] EU member states will have to develop their national restoration plans by 2026.[39] They will have to restore at least 30% of habitats in poor condition by 2030, 60% by 2040, and 90% by 2050.[40][41][42]

The regulation is a response to Europe's declining natural environments, with more than 80% of habitats in poor condition.[38] Its goals include protecting the functioning of ecosystem services, climate change mitigation, resilience and autonomy by preventing natural disasters and reducing risks to food security,[38] and restoring damaged ecosystems.[39]

The regulation was proposed by the European Commission on 22 June 2022.[43] The law was adopted in the Council of the European Union on 17 June 2024[48] and was published in the EU's Official Journal on 29 July 2024, thus coming into force on 18 August 2024 (20th day after publication).[49]Pesticides

[edit]

A pesticide, also called Plant Protection Product (PPP), which is a term used in regulatory documents, consists of several different components. The active ingredient in a pesticide is called “active substance” and these active substances either consist of chemicals or micro-organisms. The aims of these active substances are to specifically take action against organisms that are harmful to plants (Art. 2(2), Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009[50]). In other words, active substances are the active components against pests and plant diseases.

In the Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009,[50] a pesticide is defined based on how it is used. Thus, pesticides have to fulfill certain criteria in order to be called pesticides. Among others, the criteria include that they either protect plants against harmful organisms - by killing or in other ways preventing the organism from performing harm, that they enhance the natural ability of plants to defend themselves against these harmful organisms, or that they kill off competing plants such as weeds.

Within the European Union a 2-tiered approach is used for the approval and authorisation of pesticides. Firstly, before an actual pesticide can be developed and put on the European market, the active substance of the pesticide needs to be approved for the European Union. Only after approval of an active substance, a procedure of approval of the Plant Protection Product (PPP) can begin in the individual Member States. In case of approval, there is a monitoring programme to make sure the pesticide residues in food are below the limits set by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).

The use of PPPs (i.e. pesticides) in the European Union (EU) is regulated by the Regulation No 1107/2009[50] on Plant Protection Products in cooperation with other EU Regulations and Directives (e.g. the regulation on maximum residue levels in food (MRL); Regulation (EC) No 396/2005,[51] and the Directive on sustainable use of pesticides; Directive 2009/128/EC).[52] These regulatory documents are set to ensure safe use of pesticides in the EU regarding human health and environmental sustainability. The responsible authorities within the EU working with pesticide regulation are the European Commission, European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), European Chemical Agency (ECHA); working in cooperation with the EU Member States. Additionally, important stakeholders are the chemical producing companies, which develop PPPs and active substances that are to be evaluated by the regulatory authorities mentioned above.

Conservative Agriculture Spokesman Anthea McIntyre MEP and colleague Daniel Dalton MEP [53] were appointed to the European Parliament's special committee on pesticides on 16 March 2018. Sitting for nine months, the committee will examine the scientific evaluation of glyphosate, the world's most commonly used weed killer which was relicensed for five years by the EU in December after months of uncertainty. They will also consider wider issues around the authorisation of pesticides.Invasive species

[edit]

In 2016, following the EU Regulation 1143/2014[54] on Invasive Alien Species (IAS), the European Commission published a first list of 37 IAS of Union concern.[55] The list was first updated in 2017[56] and comprised 49 species. Since the second update in 2019,[57] 66 species are listed as IAS of EU concern. Since the third update in 2022,[58] 88 species are listed as IAS of EU concern, although the final inclusion of three of these species has been deferred to 2024, and one to 2027.[citation needed]

The species on the list are subject to restrictions on keeping, importing, selling, breeding and growing. Member States of the European Union must take measures to stop their spread, implement monitoring and preferably eradicate these species. Even countries in which they are already widespread are expected to manage the species to avoid further spread.[59]Government organizations

[edit]EEA

[edit]

Climate Programme

[edit]The European Climate Change Programme (ECCP) was launched in June 2000 by the European Union's European Commission, with the purpose of avoiding dangerous climate change.

The goal of the ECCP is to identify, develop and implement all the necessary elements of an EU strategy to implement the Kyoto Protocol. All EU countries' ratifications of the Kyoto Protocol were deposited simultaneously on 31 May 2002. The ECCP involved all the relevant stakeholders working together, including representatives from Commission's different departments, the member states, industry and environmental groups.[60]

The European Union Emissions Trading System for greenhouse gases (EU ETS) is perhaps the most significant contribution of the ECCP, and the EU ETS is the largest greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme in the world.

In 1996 the EU adopted a target of a maximum 2 °C rise in global mean temperature, compared to pre-industrial levels. Since then, European Leaders have reaffirmed this goal several times.[61][62][63] Due to only minor efforts in global Climate change mitigation it is highly likely that the world will not be able to reach this particular target. The EU might then be forced to accept a less ambitious target or to change its climate policy paradigm.[64]Directorate General

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

By state

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (May 2023) |

See also

[edit]- Bonn Agreement

- Coordination of Information on the Environment

- European Federation for Transport and Environment

- European Week for Waste Reduction (EWWR)

References

[edit]- ^ a b http://correu.cs.san.gva.es/exchweb/bin/redir.asp?URL=http://www.transportenvironment.org/Publications/prep_hand_out/lid:516[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Directive 2001/81/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2001 on national emission ceilings for certain atmospheric pollutants" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Terms of Reference, Working Group on the Revision of National Emissions Ceilings and Policy Instruments" (PDF). (24.4 KiB)

- ^ "EUR-Lex - L:2008:152:TOC - EN - EUR-Lex".

- ^ OJ L 296, 21.11.1996, p. 55. Directive as amended by Regulation (EC) No 1882/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council (OJ L 284, 31.10.2003, p. 1); Directives 96/62/EC, 1999/30/EC, 2000/69/EC and 2002/3/EC shall be repealed as from 11 June 2010

- ^ Kayser-Bril, Nicolas (24 September 2018). "Europe is getting warmer, and it's not looking like it's going to cool down anytime soon". EDJNet. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ "Climate change impacts scar Europe, but increase in renewables signals hope for future". public.wmo.int. 2023-06-14. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ "Global and European temperatures — Climate-ADAPT". climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ Carter, J.G. 2011, "Climate change adaptation in European cities", Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 193-198

- ^ Abnett, Kate (2020-04-21). "EU climate chief sees green strings for car scrappage schemes". Reuters. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ "EU/China/US climate survey shows public optimism about reversing climate change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "Natura 2000 - Environment - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ "Environmental Law and Practice in the European Union: Overview by Michael Coxall and Kirsty Souter, Clifford Chance LLP".

- ^ "The European environment – state and outlook 2015 – synthesis report".

- ^ "Environment Action Programme to 2020".

- ^ a b "Renewable energy targets - European Commission". energy.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ^ "Policy Brief: Bioenergy Landscape – Bioenergy Europe Statistical Report 2021". Bioenergy Europe. 2021. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ^ Hurtes, Sarah (2022-09-15). "European Union Signals a Move Away from Wood Energy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ^ "Renewable energy statistics". ec.europa.eu. January 2022. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ "EU reaches 50% renewable".

- ^ "23% of energy consumed in 2022 came from renewables - Eurostat". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ^ a b c "European Union Renewable Energy Directive, 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Share of energy from renewable sources".

- ^ Eurostat Share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption, as of January 2023

- ^ Tamma, Paola; Schaart, Eline; Gurzu, Anca (2019-12-11). "Europe's Green Deal plan unveiled". POLITICO. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- ^ a b c Simon, Frédéric (2019-12-11). "EU Commission unveils 'European Green Deal': The key points". euractiv.com. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- ^ Rankin, Jennifer (2019-12-13). "European Green Deal to press ahead despite Polish targets opt-out". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- ^ Benakis, Theodoros (2020-01-15). "Parliament supports European Green Deal". European Interest. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ Higham, Catherine; Setzer, Joana; Narulla, Harj; Bradeen, Emily (March 2023). Climate change law in Europe: What do new EU climate laws mean for the courts? (PDF) (Report). Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. p. 3. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "International investors enter Poland renewable energy market after rule change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Geden, Oliver; Schenuit, Felix; Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik (2020). "Unconventional Mitigation". SWP Research Paper. doi:10.18449/2020RP08. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ "€33 trillion investor group: strong EU climate targets key to economic recovery & future growth". IIGCC. Archived from the original on 2023-01-09. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ "Europe needs to forge ahead with renewable energy". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2022-12-23.

- ^ "Fit for 55". consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 2022-12-23.

- ^ Jaeger, Carlo; Mielke, Jahel; Schütze, Franziska; Teitge, Jonas; Wolf, Sarah (2021). "The European Green Deal – More Than Climate Neutrality". Intereconomics. 2021 (2): 99–107.

- ^ "Net Zero Coalition". United Nations. Retrieved 2022-12-23.

- ^ Mathiesen, Karl; Weise, Zia; Lynch, Suzanne (2023-08-22). "Šefčovič replaces Timmermans as EU Green Deal chief". Politico Europe. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ a b c "The EU #NatureRestoration Law". environment.ec.europa.eu. 12 July 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b "State of the Union: EU top jobs and Nature Restoration law". euronews. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature restoration: Parliament adopts law to restore 20% of EU's land and sea | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 27 February 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature restoration". Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b Manzanaro, Sofia Sanchez (17 June 2024). "EU countries rubberstamp Nature Restoration Law after months of deadlock". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature restoration law - European Commission". environment.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ "Österreich gab bei Ja zu Renaturierungsgesetz den Ausschlag, Nehammer kündigt Nichtigkeitsklage an". DER STANDARD (in Austrian German). Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "EU ministers approve contested Nature Restoration Law – DW – 06/17/2024". dw.com. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Petrequin, Samuel (17 June 2024). "EU approves landmark nature restoration plan despite months of protests by farmers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature restoration law: Council gives final green light". Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ [44][45][46][42][47]

- ^ "2022/0195(COD)". Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 concerning the placing of plant protection products on the market and repealing Council Directives 79/117/EEC and 91/414/EEC (Regulation 1107/2009). 24 November 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2005 on maximum residue levels of pesticides in or on food and feed of plant and animal origin and amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC (Regulation 396/2005). 16 March 2005. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a framework for Community action to achieve the sustainable use of pesticides (Directive 2009/128/EC). 21 October 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ "Two Conservative MEPs appointed to European Parliament's new pesticides committee | Conservative MEPs".

- ^ Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species

- ^ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 of 13 July 2016 adopting a list of invasive alien species of Union concern pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council

- ^ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1263 of 12 July 2017 updating the list of invasive alien species of Union concern established by Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council

- ^ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/1262 of 25 July 2019 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 to update the list of invasive alien species of Union concern

- ^ COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2022/1203 of 12 July 2022 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 to update the list of invasive alien species of Union concern

- ^ "List of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern - Environment - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2019-08-19. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- ^ inadim. "European Climate Change Programme – EUbusiness.com - EU news, business and politics". eubusiness.com. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Winning the Battle Against Global Climate Change" (Press release). European Union. 9 February 2005. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ R.S.J. Tol (2007), Europe's long-term climate target: A critical evaluation, Energy Policy, 35 (1), 424–432

- ^ Oliver Geden (2013), Modifying the 2°C Target. Climate Policy Objectives in the Contested Terrain of Scientific Policy Advice, Political Preferences, and Rising Emissions Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, SWP Research Paper 5

- ^ Oliver Geden (2012), The End of Climate Policy as We Knew it, SWP Research Paper 2012/RP01

- ^ "Commission creates two new Directorates-General for Energy and Climate Action". European Commission. 17 February 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

External links

[edit]- Environment at EUROPA, the portal site of the European Union

- European Commission - Nature and Biodiversity

- recyclingportal.eu